Argentine writer, Jorge Luis Borges, has a short story titled On Exactitude of Science that beautifully speaks to the dilemma of maps:

…In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

—Suarez Miranda,Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV,Cap. XLV, Lerida, 1658

We use maps to represent the spatial realities and relationships we observe. We want our maps to contain as much information as possible. However, if the map represents the reality perfectly–that is, if the size of the map is “that of the Empire”–it’s not useful. A useful map is an imperfect one that inevitably reduces the reality.

While maps may be inevitably imperfect and map-making can be inherently a reductive process, the decisions about what information could be excluded from cartographical representations are not randomly or apolitically made. Therefore, it is important to carefully examine maps to learn what histories have been excluded from the representation and what labels, toponyms, and borders have been portrayed as natural, static, immutable, and simply cartographical facts. We must be mindful of the consequences of these omissions and naturalizations that are used in dominant mapping practices through which “geographical knowledge continues to be produced, acquired and imposed as a fundamental technique of shoring up dominant conceptualizations of […] landscape” (Hunt and Stevenson 2017, 374).

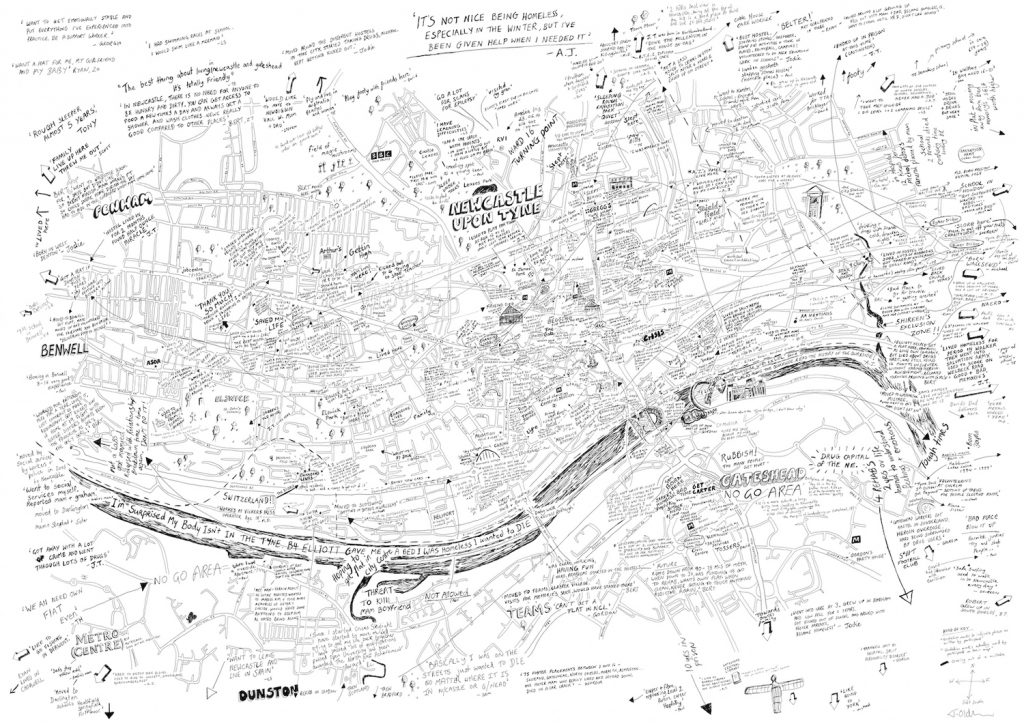

A practice of mapping critical of the claimed neutrality of dominant maps, sometimes called (counter-)mapping, contests the mainstream mapping practices that contribute to the naturalization of certain understandings of landscape at the expense of other histories attempted to be erased. As such, the goal of (counter-)mapping is to “assert alternative, potentially decolonizing geographies” (Hunt and Stevenson 2017, 373).

Most importantly, according to this critical view, maps and their constituting components, including toponyms, should be understood as texts created through an “always-already power laden,” “contested process,” and not isolated objects (Tucker & Rose-Redwood 2015, 197). As texts, maps are social constructs with their own histories and developed against the background of specific socio-cultural and political realities. They include both voices and silences, are created with a purpose and for an audience, and can be scrutinized, interpreted, and coopted (Bryan & Wood 2015).

Work Cited

- Bryan, Joe & Wood, Denis. 2015. Weaponizing Maps: Indigenous Peoples and Counterinsurgency in the Americas. New York: Guilford Puhlications.

- Hunt, Dallas & Stevenson, Shaun. 2017. “Decolonizing Geographies of Power: Indigenous Digital Counter-mapping Practices on Turtle Island.” Settler Colonial Studies, 7 (3): 372-392

- Moss, Oliver & Irving, Adele. 2018. “Imaging Homelessness in a City of Care: Participatory Mapping with Homeless People”. kollektiv orangotango+ (eds.) This Is Not an Atlas: A Global Collection of Counter-Cartographies, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. 270-275.

- Tucker, Brian & Rose-Redwood, Reuben. 2015. “Decolonizing the Map? Toponymic Politics and the Rescaling of the Salish Sea.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien, 59 (2): 194-206.