The study of interactive new media risks taking hegemonic epistemologies for granted when researchers do not critique the ways in which power inflects media creation and consumption. In “Stepping Into Futures: Exploring the potential of interactive media for participatory scenarios on social-ecological systems”, Vervoort et al. (2010) assert that “generations of ‘digital immigrants’, people that learned to make use of computers at a later age, are being succeeded by generations of ‘digital natives’ who have grown up interacting with the digital world and for whom this world is second nature” (605). Here, ‘native’ and ‘immigrant’ status are designated not by relationships to land or communities, but by the age at which a person starts using digital technology. By uncritically recycling the analogy of digital natives vs. digital immigrants, Vervoort et al. assume that conceiving of digital environments as a ‘world’ is a viable epistemological paradigm. However, such a framework erases the ongoing reality of settler colonialism and neoliberal capitalism by distinguishing the digital world from the materiality of Earth and social-ecological systems and relationships. In fact, digital technologies including artificial intelligence, new media, and virtual reality are all anchored to materiality and social-ecological relationships through their interface with humans and institutions.

Commercial social media platforms such as Facebook constitute interactive media that are funded by corporations through the neoliberal marketplace. Their ability to relay information and connect users is predicated on targeted advertising that makes use of the information users post about themselves. Recently, I was shocked to see the following ‘suggested post’ advertisement on my Facebook newsfeed:

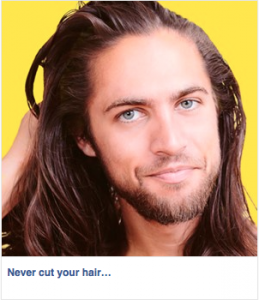

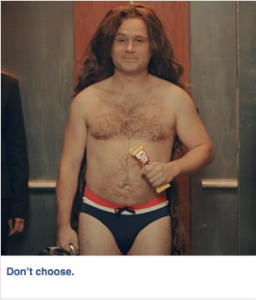

Based on my stated location of Vancouver, BC, I was selected for an advertisement for Oh Henry! Canada. However, geographical/national location does not seem to be the only selection criterion for this Facebook ad. The visual marketing strategy of this advertisement recites cisnormative gender expectations by combining two elements of gender presentation associated with femininity: long hair and bikini-style swimsuits. By juxtaposing these feminine styles of presentation with humans and a manikin exhibiting masculine secondary sex characteristics (e.g. beard, muscle distribution, body hair), the advertisers intend to portray an anomalous and humorous image of gender non-conformity. Due to institutionalized cis/sexist gender norms, bathing suit styles are a type of gender presentation that is strictly policed. In positing the assumed incompatibility of long hair and a ‘tiny bathing suit’ on white bodies (or a body model, in the case of the manikin) that are styled to suggest cisgender masculinity, Hershey normatively spectacularizes gender non-conformity. Whether or not the cisgender man (if we can assume ‘he’ identifies as a man, if not ‘cisgender’) in the final panel is wearing a wig, the tagline ‘Don’t Choose’ is meant to inspire an affective reaction of humor in the target audience of the advertisement. The humor results as a way of dismissing the dissonance inspired by the cis/sexist implication that any non-trans person assigned male at birth “wouldn’t do that”. The gender presentation of the model holding an Oh Henry! chocolate bar in the final picture is at once masculine and feminine, with the bikini-style ‘tiny bathing suit’ inflecting both masculine and feminine gender norms administered through laws against nudity in public advertising and the wig. However, the wig indicates a performance of posed femininity, amplifying the gimmicky feeling inspired by the model’s face and the Oh Henry! bar in ‘his’ hand.

The biopolitical implications of suggested posts on Facebook indicate that my geographical location is not the only personal information revealed to advertising companies. Although I currently display ‘transfeminine’ as my gender identity, Facebook undoutedly identifies me as ‘male’ in its information systems because of the binary gender option I chose when I registered my account 10 years ago. Institutionalized cisnormativity in the science of information systems and advertising means that even though I have informed Facebook that I am transfeminine, I received a personalized advertisement designed for cisgender men in Canada.

Interactive media such as commercial social media catalyze interactions between variously socially positioned users and employees. Because power is not unidirectional, hegemonic epistemologies may be distributed by the social media company or the user of the platform. Microsoft recently set an artificially intelligent robot loose on Twitter as a learning experiment, and Twitter users taught Tay.ai how to be racist. Media outlets have alternatively referred to Tay as ‘she’ or ‘it’. In this case, white supremacist users of Twitter convinced an AI user to adopt and circulate racist epistemologies. Microsoft employees claim that they neglected to prevent Tay from learning ‘offensive’ words and phrases. This discourse releases Microsoft and Twitter from any liability related to the actions of Tay without shifting the culpability onto white supremacist Twitter users.

Commercial social media have many of the resources that commercial video games garner, if not more. According to Vervoort et. al:

The diversity of communication strategies that exist within commercial gaming and to a smaller degree in the serious gaming world offer a world of opportunities…But these techniques have to be built from scratch. Certain types of commercial game setups lend themselves relatively well for straightforward adaptations, as Herwig and Paar [62] show by using a game engine for the visualization of environments. But when we want to make use of more complex game characteristics such as artificial intelligences and intricate interaction procedures, the amount of resources needed to mimic these elements increases steeply. (2010: 609).

Although social media and video games differ in genre, both are corporatized and make use of a “diversity of communication strategies”. In fact, Facebook has custom and commercial games embedded within the platform. Microsoft’s Tay.ai initiated the use by artificial intelligence of commercial social media. Whether Tay learned how to spew racism and sexism from both user input and commercial advertisements on social media or only from white supremacist users, ads cannot be ignored when analyzing the communication strategies of social media. Rather than assuming that commercial interests are neutral or benevolent, research on interactive media should acknowledge that institutionalized racism, settler colonialism and cis/sexism work through the corporations and denaturalize the fact that corporations possess the means of production of media technologies and the artificial intelligence interacting with social media.

References

Oh Henry! Canada. (ca. 2016). In Facebook [corporate page]. Retrieved March

30, 2016, from https://www.facebook.com/OhHenryCanada/?fref=ts

Rankin, Kenrya. (25 March 2016). “Microsoft Chatbot’s Racist Tirade Proves

that Twitter is Basically Trash.” Colorlines. Retrieved from https://www.colorlines.com/articles/microsoft-chatbots-racist-tirade-proves-twitter-basically-trash