The Proclamation of 1763 and Europeans Stories

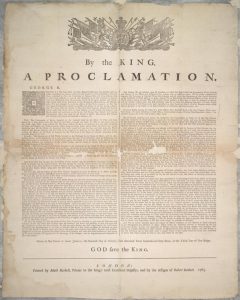

The Proclamation of 1763 is a set of guidelines for the European settlement of the Aboriginal territories in North America. Issued by King George III in 1763, as a way to officially claim North America as British territory after beating France in the Seven Years war[1]. The proclamation established the ownership of all of North America to King George.

Interestingly enough the document states that Aboriginal title had existed and continues to exist and that all land must be considered Aboriginal land until ceded by treaty to others. This recognizes Aboriginal titles and claims to land and that it requires both parties to give consent when land is being exchanged, even though it was written by the British without Aboriginal input. It forbade settlers from claiming Aboriginal land, as it must first be bought by the Crown and then sold to settlers, and only the Crown has the power to buy land from First Nations.

The reason that the British took action in promising First Nations protection under their law was to try and stabilize the western frontier of the Atlantic colonies. In the same year, 1763, there was an emerging of Indigenous confederacy under Odawa, that had seized some British military posts near the Great Lakes[2]. This was mainly because the Aboriginals at the time we’re able to play the British and French off each other to secure themselves, but with the loss of the French, arguably the side the Aboriginals were more inclined towards, they had to establish a stronger hold, which resulted in Pontiac’s War[3].

With the fact that the Seven Years War had been very costly to both the French and the British, economically crippling France and leading to the French Revolution, the British were wary of getting into another conflict[4]. After these incidents of violence, the British wanted to establish an allegiance with the First Nations to avoid further large-scale conflict, as many had been allied with France[5]. This proclamation allowed for a resolution, while avoiding further conflict in the area.

In relation to Daniel Coleman’s, White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada, I think the Royal Proclamation of 1763 does demonstrate that Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility does hold weight in this situation.

Coleman argues that in the early projects of nation-building there has been an  endeavor to present a form of Canadian whiteness based on British civility (5). So the idea of White Canadians is one connected with British civilized society. Imaging Canadians in the 18th and 19th centuries in standard British town clothes and dealing with more ‘intellectual’ or ‘civilized’ aspects, that turn away from narratives of violence. Yet this is only done when one learns to forget the uncivil acts of colonization and nation-building. The Royal Proclamation fits into this narrative, as the document itself does not mention the reason for its existence, but it is because there is violence between colonizers and the Aboriginal people of the land. Colonization and expansion into West of the original Atlantic colonies was a violent act, which Aboriginals resisted with equal force. The reason the document came to be was that now with the French gone, there was no one to stop the colonies from expanding into the ‘new’ territory. The Aboriginals knew that and that is why the tried to resist in Pontiac’s War. But this document doesn’t mention the situation and calls all the people of the land as under the King’s rule, even though no one believed the Aboriginals had any real rights to the land or even considered them people under the same ruler. It tries to hide past violence and struggles to stop new violence that is bound to happen in the situation. And violence does happen, many historians cite this document to be a reason for the American Revolution, people wanted to expand and refused to abide by the decoration, expanding to the West either way[6]. The proclamation asks us to forget the violence that lead up to it and the future violence that is inherent to colonization. To colonize another is to subjugate a society under your rule and to enforce this rule violence is the main tactic. The continuation of colonization rests on violence and subjugation not on the story of civilization that many would like to believe.

endeavor to present a form of Canadian whiteness based on British civility (5). So the idea of White Canadians is one connected with British civilized society. Imaging Canadians in the 18th and 19th centuries in standard British town clothes and dealing with more ‘intellectual’ or ‘civilized’ aspects, that turn away from narratives of violence. Yet this is only done when one learns to forget the uncivil acts of colonization and nation-building. The Royal Proclamation fits into this narrative, as the document itself does not mention the reason for its existence, but it is because there is violence between colonizers and the Aboriginal people of the land. Colonization and expansion into West of the original Atlantic colonies was a violent act, which Aboriginals resisted with equal force. The reason the document came to be was that now with the French gone, there was no one to stop the colonies from expanding into the ‘new’ territory. The Aboriginals knew that and that is why the tried to resist in Pontiac’s War. But this document doesn’t mention the situation and calls all the people of the land as under the King’s rule, even though no one believed the Aboriginals had any real rights to the land or even considered them people under the same ruler. It tries to hide past violence and struggles to stop new violence that is bound to happen in the situation. And violence does happen, many historians cite this document to be a reason for the American Revolution, people wanted to expand and refused to abide by the decoration, expanding to the West either way[6]. The proclamation asks us to forget the violence that lead up to it and the future violence that is inherent to colonization. To colonize another is to subjugate a society under your rule and to enforce this rule violence is the main tactic. The continuation of colonization rests on violence and subjugation not on the story of civilization that many would like to believe.

[1]‘Royal Proclamation, 1763’ <https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/> [accessed 28 February 2020].

[2]‘Royal Proclamation of 1763 | The Canadian Encyclopedia’ <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763> [accessed 28 February 2020].

[3]History com Editors, ‘Ottawa Chief Pontiac’s Rebellion against the British Begins’, HISTORY<https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/pontiacs-rebellion-begins> [accessed 28 February 2020].

[4]‘Royal Proclamation of 1763 | The Canadian Encyclopedia’.

[6]‘Royal Proclamation of 1763 | The Canadian Encyclopedia’.

Reference:

‘A Bi-Polar History of Canada The 18th Century: The Age of Reason (at Least in Europe) – Salem-News.Com’ <http://www.salem-news.com/articles/october072012/bipolar-canuk-ba.php> [accessed 28 February 2020]

COLEMAN, DANIEL, White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada(University of Toronto Press, 2006), JSTOR <https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442683358>

Editors, History com, ‘Ottawa Chief Pontiac’s Rebellion against the British Begins’, HISTORY<https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/pontiacs-rebellion-begins> [accessed 27 February 2020]

‘First Nations | The Canadian Encyclopedia’ <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/first-nations> [accessed 26 February 2020]

‘Royal Proclamation, 1763’ <https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/> [accessed 26 February 2020]

‘Royal Proclamation of 1763 | The Canadian Encyclopedia’ <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-proclamation-of-1763> [accessed 26 February 2020]

Hi Nargiza,

Very interesting read! I totally agree that violence is a core element of colonization and that no new territories are acquired through fully peaceful means. It is ironic that forgetting past brutalities and violent acts of colonization was essential to the formation of a document aimed at preventing the same violence.

I personally think that acknowledgement, not forgetfulness, should have been used in drafting the Royal Proclamation. Instead, the Crown chose to forget and unsurprisingly, the prevention of colonial expansion towards the west was temporary. In fact, violence, more than likely, was not eliminated. It is just that colonizers had to go through the Crown to receive permission to move towards the west and continue to colonize lndigenous lands. How different do you think the Royal Proclamation would have affected subsequent bouts of colonization and settler-Native relations if the Crown had chosen to acknowledge their past faults instead of forget them?

Thank you,

Chino

Hi Chino!

Thanks for your comment. To answer your question, I think acknowledgement is crucial and has to come to fruition if we ever want to continue beyond hiding behind the stories we tell ourselves, or rather the lies we tell ourselves to justify our reasons. If the British had acknowledge the violence between them and the First Nations if would ruin the idea of White Civility, and I would have hoped that it would then play an important role in self realization. But it could also have done nothing, as during that time period it was hard for settlers to sympathize with those that they deemed below human. I don’t believe people are inherently bad and books such as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” have worked hard in trying to bring forth the truth of violence that colonization has produced.

In that time period, I would say that they would have to have done a lot more than simply admitting to violence to stop violence. We see that most clear in slavery in America, where people become so immersed in their story of master and slave that they ignore everything else. Even with Bartolome de las Casas, a historian and missionary, who became the first person to expose the oppression and subjugation of the First Natives by the Spanish in his book, “A History of the Indies” and called for an end to their inhuman treatment, was a believer that it was fine to in-slave African’s, those with black skin. In this time violence was justifiable in order for goals to be met and for this reason I can say that admitting to violence might have helped in the long run, but the violent treatment might have not ended. Even now days, we can admit to the violent actions of our history but we might still refuse to do anything about it. We might even distance ourselves from these acts by saying that we have not done these actions ourselves and disavow them, but in the end without real effort to change, things generally stay the same.

It’s such a big question to ponder and I don’t feel like I have the qualifications to even guess where to start to answer your question, but I tried my best and I hope I gave you something to think about!

Hi Nargiza!

I appreciate your detailed dive into the history of this! Going off of Chino’s comment from above, I think about how violence still manifests in different ways now – whether it be criminal-stereotyping in specific communities or culture-assimilation. I view assimilation or subjugation of communities/cultures to be a violence against them. Do you feel like there are some more “subtle” ways that this type of violence still appears in our society?

I wonder if acknowledgement is enough at times. When I look back on my high school Canadian history studies, I don’t view it very positively as it seems to hold a very neutral, matter-of-fact perspective (which is basically a one-sided perspective). Do you feel like diving into the matters around our history in whole will better achieve fairness? Or do you think that somehow this dives into the politics of today? Perhaps the fact that our history and politics get muddled together sometimes speaks to the importance of putting emphasis in acknowledgement?

Hi Lisa,

Thanks for your comment! I find the idea of violence and subtle violence to be really interesting. For me the idea of violence comes in different forms, we often see it as large forces or acts that engulf people and seem to stall everyday normality. But the truth it, the continuation of our everyday lives relies on background violence that we’ve learn to ignore or be desensitized to. Things such as violence against refugees/immigrants, that we see in borders, or violence to women around the world, or violence to poverty stricken individuals both in our own backyards, and in factories producing the very laptops that we’re using. Or maybe even the weapons that European countries sell to African governments, it can be the funds that the USA government provided to Mexico to crack down on refugees/immigrants coming from South America, or the way the Chinese government uses it’s market power to threaten countries to be silent when human rights come into question. It’s all just background violence that is needed so that our normal everyday lives can continue. In that way I think our lives are surrounded by violence we’ve learned to or chosen to ignore. It is the type of violence that maintains our social order. Similar to our legal violence, we authorized violence by the law in a way that overcomes our morality, such as the death penalty, as if killing someone under the hand of government is different from man to man murder.

In terms of education, I was a deep lover of history in high school, but also felt that the portions on First Nations were dull and uninteresting. It’s only when I was older and started to learn about the inherent violence that comes from history did I really come to understand the world in more complex ways. But I’m uncertain at what age one would have to teach this type of history. It’s always important to learn, even if one doesn’t want to get into politics, I feel like it might have done me better to learn even a bit about the violence rather than the type of drum that they used in certain ceremonies.

Hi Nargiza, in Harry’s Robinson’s story of the Black and White Twin, Coyote went to the King of England and they wrote a paper together to protect the rights of First Nations. I’m wondering if this is the Proclamation of 1763, and if so, did someone from a First Nation’s community really go to England to see the king? Do you see any other aspects of the story that correlate to the events before, during, and after the creation of this proclamation?

-gaby

Hi Gaby,

Thanks for your comment. Unfortunately the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was made without any consent and input from the First Nation community. I’m not actually sure if Robinson’s story is related to the Royal Proclamation, but if I may take a guess, Robinson’s story sounds more similar to the Constitution Act of 1982 Section 35. When the First Nation people of Canada came together to force the Canadian government to reaffirm Aboriginal rights in the Canadian Constitution. One of the main protests that pushed the government to do so is the constitutional express. Where First Nations worked to gain international audience in the United Nations and the British Parliament in order for their grievances to be heard.

You could check it out here: https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/constitution_act_1982_section_35/

It’s an interesting question, but rather than the Royal Proclamation I’d suggest it’s a more recent event that inspired the story!