HELLO, This week I had the absolute “pleasure” of investing my blood, sweat, and tears into Derrida’s Archive Fever. I must say, that although very challenging (I am not well versed in the psychoanalytical concepts presented by Derrida) I enjoyed the task of finding connections to the archives, specifically the Jack Shadbolt collection. I am going to spend this blog discussing a subject that we did not have the time to cover in our presentation on Derrida last week, which is, the idea that there is no true archival memory.

Firstly I’d like to look at how Jack represents both himself, and his community in his archives. We have been entertaining the thematic idea of how an artist represents themselves in their archive. What I have noticed especially interesting with the Shadbolt’s collections is his interest in how society is represented. His fonds, when are about him, typically reflect a more public view of him.

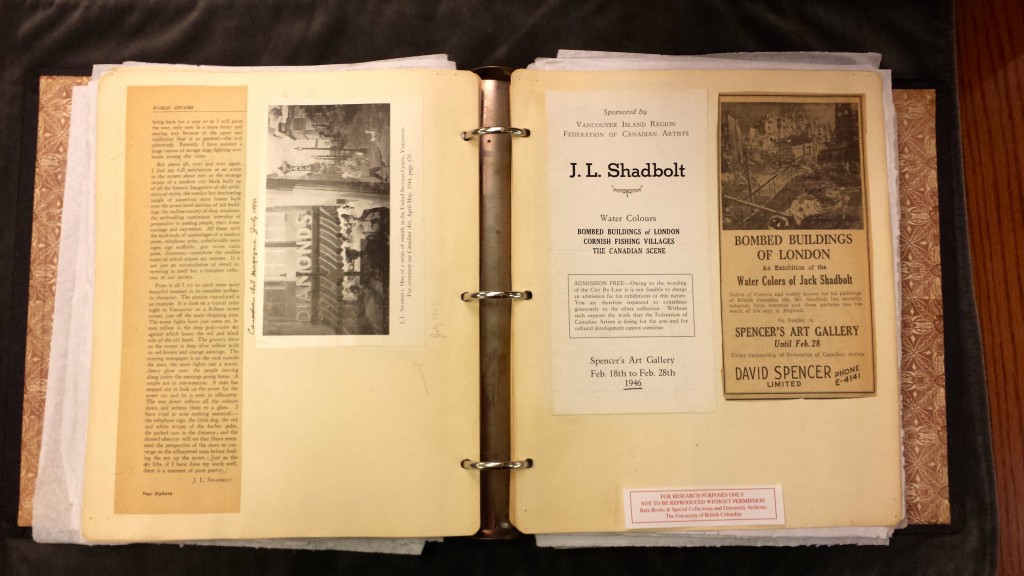

Box 32, ARC 1493. Scrapbooks.

Box 32, ARC 1493. Scrapbooks. “But above all, over and over again, I find my full satisfaction as an artist in the streets about me: in the strange façade of a modern city block built up of all the historic hangovers of old architectural styles . . . It is not just an accumulation of detail interesting in itself but a complete reflection of our society.” World Affairs Page 18

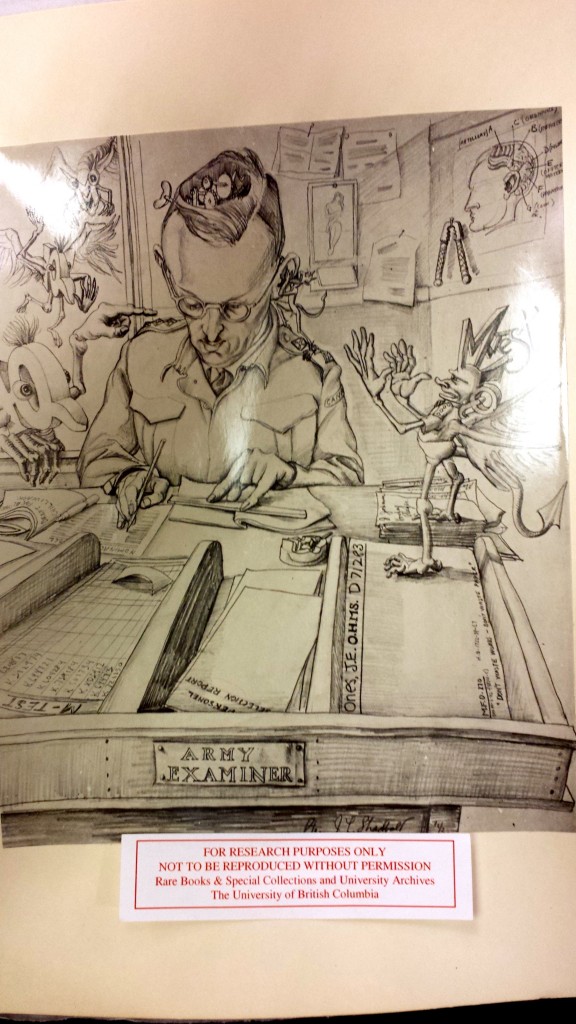

Jack seems captivative in capturing The Society rather than just himself. His collection consists of army images, native reserves, shipping docks, the aftermath of the war, and landscapes which all encompass something bigger than him.

A distinction should be made, between the violence, as we know it, and the violence that Derrida describes. For the purpose of this presentation we will refer to the violence, as we know it as the “literal violence.” He illuminates that there is a violence of the archive and it repeats in a distorted way. This violence is at the very root of the archive, which both informs and originates the archive. Firstly, the archive is an act of repetition and secondly, the repetition is distorted; it is unfaithful. That is to say, the archive is repeated in a distorted form; therefore it is deferred action and repetition compulsion.

In a repressed way the violence (repression and distortion) of the literal violence we know occurred repeats through the Shadbolt paintings. Shadbolt was an official War Artist in the Canadian Army during World War II. Because we can’t look at an archive and physically point out the violence, the other is a correlation between Derrida’s notion of violence and the archives we are viewing but it is not the equivalent. To say the archive deals with violence in one way would be doing violence with, or to, violence.

Additionally to the already considered violence within the army paintings, there is a demonstration of how the archive, acting as both a concept and place in an institution, repeats this violence of the physis and nomos because it is being collected as a one. For this reason, we can present the idea that we are repeating this violence in our act of archiving these things, which brings us nicely to support Derrida’s idea of the death drive.

Looking at some of the images from Shadbolt’s collection we see War paintings intertwined with creative distortions (ideals, stigmas, beliefs, paradoxes, political insights, etc.) The remainder of the war has to be distorted because it is a repressed trauma. The death drive wants to destroy memory because through repeating that repressed memory. The hypomnēma is repeated memory, it’s external memory, which is the archive (prosthetic memory) and in this repetition Derrida sees this death drive similar to Freud. Where Derrida turns this notion around is when he says the death drive is not simply the compulsion to create that external memory, it’s also trying to erase that memory, unless, if it can be distorted, then that memory can survive.

From this we can derive that there is no true archival memory; the distortion is just a representation of the idol of the truth. The memory can survive so the death drive is compelling us to repeat the repetition while also persuading us to destroy it because it’s horrific connotations. Again, it is this distortion which leaves an imprint (repression) that can be brought back to the arkhe and the concept of the archive sheltering in itself two irreconcilable concepts: the thesis and the nomos.

This leaves me to ponder on the idea of the fallacy of the archival memory. I’ve already toyed with the notion of how representation of oneself comes into account as we see artists selling their archives to institutions whilst, of course, still living. This now also questions the authenticity of the archive, even from those who have passed. That fact they, because of repression, have only preserved a distortion of the true memory. I don’t expect anyone to provide an answer to this, I surely cannot, but I am interested to hear what you think about the idea that there is no true archival memory.

Until Next Time,

Best.

Works Cited

Derrida, Jacques. “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.” Diacritics 25.2 (1995): 9-63. JSTOR. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.