HELLO, what a week it was in the archive world for me. Rather than spending time in RBSC, I instead looked through fonds in the UBC Museum of Anthropology. The MOA states their commitment to respecting the values and spiritual beliefs of the cultures represented in its collection, however, the reading this week by Laszlo remained at the forefront of my mind while looking through the files from the Beverly Brown fond. Laszlo takes up a controversy aspect regarding museum collections – the concept of Cultural Property in direct relation with First Nations content. Laszlo covers how there is a distinction between Property and Cultural Property:

“In a Western Tradition, property is something that is owned or belongs to some person or persons, Legal definitions include rights that attach to those who are owners and determine what uses one can make of one’s property. Cultural property is defined as the material manifestations that relate to a civilization, especially that of a particular country at a particular period.”

Unfortunately, these do not apply to the First Nations content because of their inability to encompass the entirety of heritage. First Nations culture was based sturdily on orature, spirituality, and soul. Secondly, (and more obviously) complications arise when you have collections created by people, not within the realm of whom they represent. Now I think these two points are vastly important when looking at First Nations archives. We have to remember that these archives were preserved in the first place because there was “concern” that these cultures would become extinct in a short time. The paradox of this mentality is that, of course, this fear was derived as a direct result of the Colonization and Western body that came to BC and overtook the First Nations lifestyle, forbidding their expressions of culture and heritage. To now look back and realize the wrongdoing is, at least, responsible but where I was being rubbed the wrong way and where Laszlo also draws attention to is that idea that the First Nations hold moral ownership over the archives, and as Deborah Doxtator mentions, “you must always ask someone else to see what is ‘morally’ yours.” Now we are opening another realm of complications – one that tends to turn up often in academia – the issue with accessibility. As noted, these archives were not originally compiled to benefit the First Nations communities, but preserve their essence in an archive. I feel this translates negatively when now viewing them today. If the archive wasn’t created for those who “morally” own them, and they also weren’t created by those who “morally” own them, then there is a clear disconnect from the culture they supposedly represent and the archive itself. Doesn’t seem to be very moral at all does it?

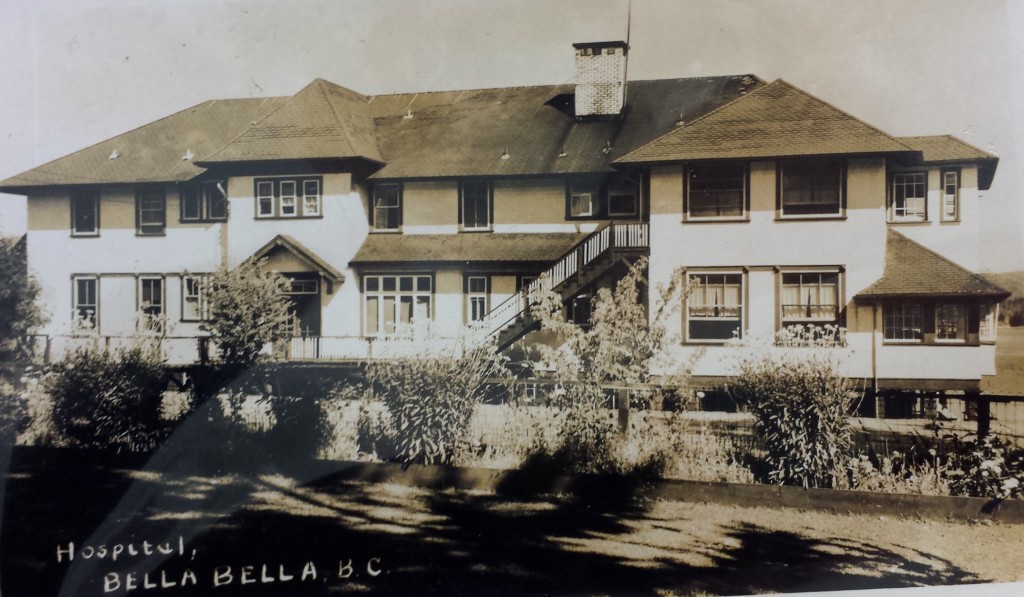

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has been facing many questions pertaining to this very concern. The lack of Truth in the archives and lack of Reconciliation on behalf of the museums seems to be clear and while there are steps being taken to correct these concerns, the final outcome is yet to be seen. As mentioned in the Laszlo article, we need to “establish guidelines to handle ethnographic records that are currently in our archives and to understand the moral and ethical responsibilities of archivists who care for these types of materials” (Laszlo, 307). The following images were taken from the Beverly Brown fonds and show students of the St. Michael’s and Bella Bella Residential Schools. I feel they clearly show the concerns mentioned in this post, the lack of authentic First Nation culture and heritage and a dominating colonial influence. While the residential schools are a dark seed in BC’s history, one forever embedded in First Nations history, I am saddened that it dominates the First Nations archives. Due to the unique nature of oral history, dance, language, and spirituality, and the neglect and misunderstanding from those who composed these archives, we loose so much of a culture’s heritage and continue to misrepresent it with fonds such as this one. In terms of Cultural Property, we need to query what culture this fond truly represents and whose property it actually is.

St. Michael’s Residential School Photographs (Files 1) and Bella Bella Photographs (File 2) of the Beverly Brown Fonds at the Museum of Anthropology.

Article Source:

Laszlo, Krisztina. “Ethnographic Archival Records and Cultural Property.” Archivaria 61 (2001): 299 – 307.

Websites:

http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=3

http://moa.ubc.ca