Is it Un-Canadian to suggest medical care spending should not increase, at least not faster than our economy grows? I fear many think it is.

During the last federal election, not a single Party challenged the idea that federal transfers for medical care should increase six per cent annually until 2014. And as provincial, territorial and federal health Ministers met recently in Halifax to consider what will happen thereafter, I couldn’t track down a single mainstream media article that questioned the idea that medical care spending should grow.

Here’s a newsflash Canadians, especially to those on the centre-left of the political spectrum. There is ample reason to worry that our current approach to medical care spending may be making us more sick and stupid.

When many Boomers came of age between 1975-1980, the Canadian Institute for Health Information shows that we spent 5.4 per cent of our gross domestic product (GDP) on publicly funded medical care. By 2008, before the recession took hold, Canadians had increased spending to 7.6 per cent of GDP. It’s now closer 8.4 per cent, in part because economic growth has been stagnant since. This means we spend $47 billion more today on medical care than we would have had we maintained public spending at the same level as 1975-1980.

Over the same period, Statistics Canada data show that total revenue collected by the federal, provincial/territorial and municipal governments didn’t grow by even half that amount. The result? The total revenue pie does not keep pace with its largest slice — medical care. This means billions less for other social priorities.

Social service spending is chief among the casualties, as is education spending. As a share of the economy, spending in BC on each of these areas fell 0.7 per cent of GDP. This may not sound like much, but with similar declines across provinces, we’re talking about a combined $21 billion reduction – enough to pay for a New Deal for Families.

Behold further evidence of Canada’s bad intergenerational deal. Reducing social service spending means limiting child welfare, child care and poverty reduction. Reducing education spending clearly limits kids’ opportunities to learn. By contrast, increasing medical care enriches a transfer disproportionately for older Canadians.

As the population ages and the risk of frailty and illness grow, we can all understand why medical care is a top priority. But do we really think we can grow medical care spending indefinitely without increasing taxes by a corresponding amount? So far, this plan has been sustainable only by compromising investment in programs and income supports for younger Canadians.

If Canadians aren’t interested in raising taxes, then let’s seriously consider capping medical care spending.

Even if we are open to raising new revenue, there is good reason to allocate it to things other than the status quo approach to health care in this country. Medical care is yet another example of Canadians generally dealing with problems after the fact, rather than preventing them in the first place. For instance, we know the time, income and service squeeze on the generation raising young kids increases work-life stress. Linda Duxbury and Chris Higgins at the Sprott and Ivey Schools of Business show that work-life stress among Canadians accounts for 30 to 40 per cent of avoidable spending on prescription drugs, hospital accommodation and visits to health professionals like physiotherapists.

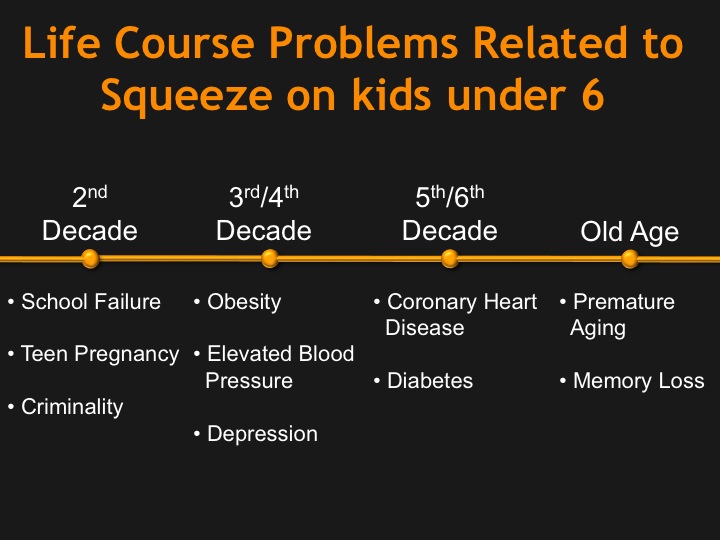

Equally important, the time, income and service squeeze explains why 30 per cent of young kids start school vulnerable. In addition to doing worse in school, their vulnerability means they are more likely to become obese, have high blood pressure, struggle with mental illness, get diabetes, suffer coronary heart disease and premature memory loss. If we have a disease fetish, then we are on the right track by ignoring Gen Squeeze. But if we want to reduce medical care spending on their kids in the future, we need to eliminate the squeeze on parents now.

Trade-offs. There’s no doubt that life is full of tough ones. Presently, Canadians trade lower taxes for less investment in citizens under 45. We choose more money for illness treatment instead of spending on health promotion through a New Deal for Families when citizens are younger. It is important to be clear that we perpetuate these trade-offs by accepting the argument that the Canada Health Transfer ought to increase six per cent annually as Ministers head into 2014 Health Accord negotiations.

Trade-offs. There’s no doubt that life is full of tough ones. Presently, Canadians trade lower taxes for less investment in citizens under 45. We choose more money for illness treatment instead of spending on health promotion through a New Deal for Families when citizens are younger. It is important to be clear that we perpetuate these trade-offs by accepting the argument that the Canada Health Transfer ought to increase six per cent annually as Ministers head into 2014 Health Accord negotiations.

If you don’t like these trade-offs, the time for tough questions is now. For instance: what medical care do well-intentioned, kind-hearted Canadians owe one another when our capacity to treat illness improves with increasingly costly technology and drugs?

Right now, it is electoral suicide for politicians to publicly contemplate this question, whether on the left or right of the spectrum. We need to change this dynamic.

Tommy Douglas led Canadians toward our greatest social policy achievement. The birth of medical care meant that Canadians no longer had to face bankruptcy when they lost out in the lottery of ill-health and wound up in hospital. From coast to coast, his legacy is that Canadians will pay to go that extra mile to help those who become sick. This is something for which we can all be proud.

But our greatest policy achievement is now a barrier to investing in new social policy, especially as government revenue declines relative to the size of our economy. So long as we fail to question the value of increases in public medical care, we literally risk our health by failing to invest in its social determinants. Regrettably, it is the generations that follow the Boomers who bear the brunt of this problem.