What should be the retirement age? The Prime Minister deserves credit for provoking debate about a policy issue that is unlikely to help him electorally.

The fact is we are living longer. Compared to 1970, women today live on average seven years more; men, an extra decade. Given this change, it is hard to argue against adapting Old Age Security and Canada Public Pension policy by raising the retirement age beyond 65. These systems weren’t designed for the reality that “70 is the new 60.”

But here’s the thing. Any change in retirement age is not about today’s seniors. It’s about the working lives of younger Canadians. Government spokespeople have insisted, and rightly so, that any change wouldn’t affect those who are already age 65 or older. Rhetoric to the contrary is misleading.

A change in the retirement age is an issue for Canadians who are currently planning their retirement based in part on the expectation that full OAS and CPP benefits will be available at age 65. Policy reform must be phased-in so that those in this group have ample time to adapt their plans. The need for adequate transition time means that we likely won’t see Canadians who are currently 55 or older feeling the effects of pending reforms. The peak of the Baby Boom generation could slide into retirement before changes take effect – yet another example of that demographic group winning in the lottery of good timing.

What should younger Canadians think of later retirement?

As part of my national “Think like a Beaver” speaking tour, I encourage citizens under 45 to accept a later retirement age as a reasonable policy adaptation to demographic changes since the 70s. But if we are to adapt policy in response to changes in life expectancy, we should also adapt policy to other, equally stark, demographic trends. One example is the rise in dual-earner households.

Employment standards defining full-time work still reflect the assumption that households will have one person specialize in breadwinning while the other specializes in caregiving and domestic work. Most households no longer operate this way. Feminism is one part of the reason, but so too is the fact that wages haven’t kept pace with the cost of living. Household incomes for young couples have stalled since 1976 even though far more young women contribute employment income. For Canadians under 45, two earners are generally required to carve out a standard of living that is falling behind what one earner could often achieve a generation ago.

Although the rise of dual earners is a reality, must it be that both earners work 40-plus hours per week, for 49 or 50 weeks a year – the norms that were established following World War II? This trend contributes to a major time squeeze at home, especially for employees with young children.

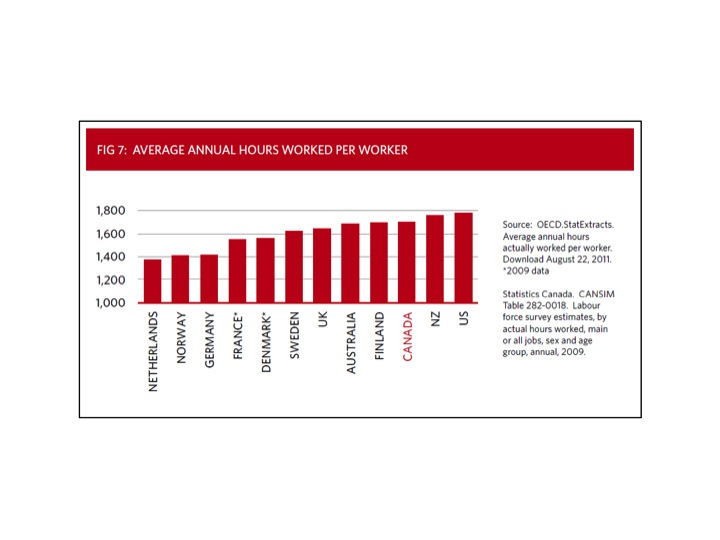

Although Canadians say we espouse family values, our workplace standards mean the typical Canadian employee works 300 hours per year more than the typical Dutch, Norwegian and German employee for about the same average income. While higher housing prices make this commitment to the labour market understandable economically, all these extra hours of work erode the opportunity to be home with children or care for aging parents. 59 percent of Canadian men age 25-44 and 34 percent of women age 25-44 work 40 or more hours per week.

While Canadians under 45 may have to (begrudgingly) accept a later retirement, we should tolerate these extra years of work in return for employment norms that adapt to the reality of dual earner homes. This would mean some tinkering with the definition of full-time work, adjusting it to 35 hours/week on average over a year, rather than 40-plus. An extra 5 hours per week, and sometimes 10 for a two-earner household, can make a HUGE difference when it comes to mitigating the time squeeze. And even with this change, we’d still be working almost 150 hours more per year than in the Netherlands, Norway and Germany.

There are ways to do this that are good for employers and employees alike. We could adapt overtime and EI premiums paid by employers to make it less costly for businesses to use employees up to 35 hours per week, and more costly for hours thereafter.

For employers, there are productivity gains to be made from this switch. Although typical Dutch, Norwegian and German citizens may work fewer hours than Canadians, their productivity per hour is higher. When France shifted a decade ago to the 35 hour work week, it did so with the intention of reducing unemployment. Data now show that shorter hours didn’t contribute much to this objective, because employers didn’t replace a very large share of the reduced hours with new workers. It wasn’t necessary, because productivity per hour increased.

For the half of men and the third of women who currently work more than 40 hours per week, work hours would be reduced by an average of 3-5 hours per week. In some cases, employees may trade a bit of after-tax income (or better yet, future wage increases) in order to gain four more weeks of time per year. In negotiation with employers, this time could be taken in chunks, or as earned hours away from work each week throughout the year.

Changes to the National Child Benefit Supplement could ensure any reduction in employment hours does not reduce income for low-earning families, which may be especially important for some lone parent households. When combined with $10/day child care and New Mom and New Dad benefits, families with preschool age kids would generally have more disposable income. Plus they would be enjoying the extra time at home when they really need it.

Shorter work years for longer work lives. This trade-off merits serious discussion among younger Canadians as we adapt policy to longer lifespans and the tightening time squeeze at home.