When I was in my senior year of high school, my English literature class studied John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath. Steinbeck’s compellingly compassionate depiction of the dust bowl impoverished Joad clan, along with my teacher’s committed socialism, provoked cognitive dissonance: my newly discovered knowledge surrounding socio-economic inequity forced me to confront my own privilege and the realities that lay outside of my suburban, upper middle class existence.

My response to this cognitive dissonance has manifested itself at various points throughout my life. While pursuing my undergraduate degree, I worked part-time in the City of Ottawa’s subsidized housing department; during this time I discovered to my growing anger and frustration some of the systemic causes of poverty and how pervasively intergenerational poverty could become. And although my graduate and subsequent research focused on early modern drama, the material conditions of the production of this drama formed a significant part of my study. Most recently, I was a classroom volunteer for Take A Hike, an outdoor education alternative school based at Sir John Oliver Secondary in Vancouver, BC. While some Take a Hike students are from middle class homes, most come from families at or below the poverty line. The Take A Hike program adapts both resources and discourse to reflect their learners’ reality: the program has its own stocked kitchen, thereby mitigating the effects of food insecurity; and socioeconomic concerns are given discursive priority in classroom discussions.

When it was time to develop a topic for my inquiry my thoughts turned both to my own classroom experience with Steinbeck, and to Take a Hike its their consideration of poverty in the classroom and in the lives of the program’s students. In my preliminary reading, however, I found it difficult to find articles that dealt explicitly with poverty in the classroom: socio-economic concerns were rarely discussed on their own, but were frequently gathered among other dominant discourse inquiries such as ethnicity and gender. Discussing this difficulty with my cohort leader helped me express my concern about the representation of socioeconomic status in the classroom discourse. Put another way, how do we talk about class in the classroom?

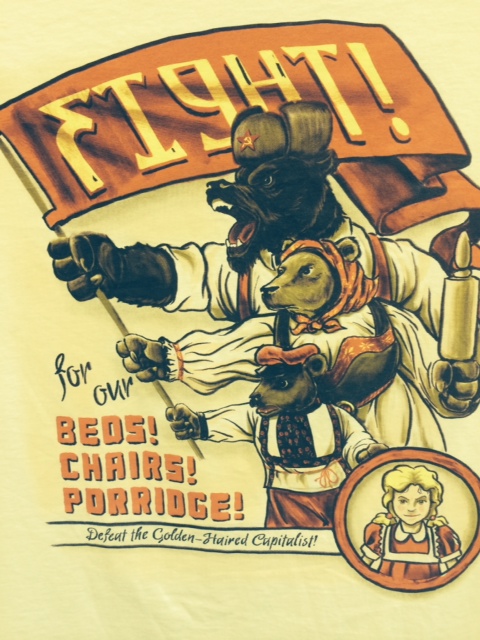

The Golden Haired Capitalist: A t-shirt displayed in a classroom at my practicum school, one of the few visible artifacts prompting a discussion of socio-economic class.

My inquiry is framed by post-structuralist discourse analysis which views educational sites as spaces where power, ideology, and cultural capital are reproduced, negotiated, and resisted; this discursive negotiation is closely connected to the function of education in shaping the identity of students. Oftentimes, for instance, awareness of socio-economic status, represents poverty as deficit, as a problem to be redressed. This perspective has the potential to create misrecognition in students in poverty. This discussion of deficit discourse, however, is a treacherous road to walk because the ill effects of poverty cannot be denied and must be remedied, yet students themselves must not be negatively characterized.

I hope that my inquiry will be able to shed some light on the often ignored construction and discussion of class in middle class normative schools. Expanding discussion in this area will create an opportunity for all subjects—students and teachers, regardless of class—to locate themselves within the rhetorical space of the classroom. With one in five children in British Columbia living in poverty, our classrooms can no longer afford to remain silent.