It has only been the past two decades that tourism became increasingly popular in Iceland. While this is partly due to the overall increase of tourism worldwide, media sensationalism has played a role in popularizing Iceland as destination as well. I was inspired from Andri’s lecture to understand the relationships between the environmental movement in romanticizing Iceland’s landscape.Therefore, I will examine this through looking at literature, film, music, and tourism campaign.

Early stages of the environmental movement

For Icelanders and tourists alike, people can feel a special connection between the landscapes of Iceland and humans. From the “eternal glacier” that is Vatnajökull, to the powerful waterfalls that is Gullfoss, they illustrate the immense difference of geological timescales all comprised on an island. As a student, I feel humbled by such sites to reflect upon not only on the anthropological changes we bring about, but also how we are integrating the Icelandic environment in our literature. In this regard, Andri’s book Dreamland: A Self-Help Manual for a Freightened Nation is significant in starting a conversation to rethink industrialization and environmental protection. His book comments on the façade of “clean energy” that hydropower puts forth, and the wasteful nature of aluminum smelters (Magnasson, 2006). He states that the dams built to create the hydropower plant is harmful for the central highlands, which is regarded as pristine and untouched wilderness (2006). He takes an eco-critical approach to Icelandic environment literature, which I believe was the beginning of sparking international attention for the country.

Music in the environmental movement

Since the late 1970s, Bjork has been a major influence in the European alternative music scene. She is known for her raw, experimental and often referred to “childlike” music style (Pytlik, 2003). After Andri’s book was released in 2006, she along with Sigur Rós and other artists hosted the Náttúra environmental concert to raise awareness on the harmful effects of the hydropower plants. The concert was broadcasted by National Geographic with many reporters present for the event, which brought the country’s beauty to the public eye. This event gave the landscapes of Iceland a persona because Björk and Andri led people to think about the environment more critically. Her song Desired Constellation, for example, captures the Icelandic landscape beauty very well. The line “With a palm full of stars I throw them like dice” is used as a metaphor for destiny (Björk, 2004).

Filming increasing popular media exposure

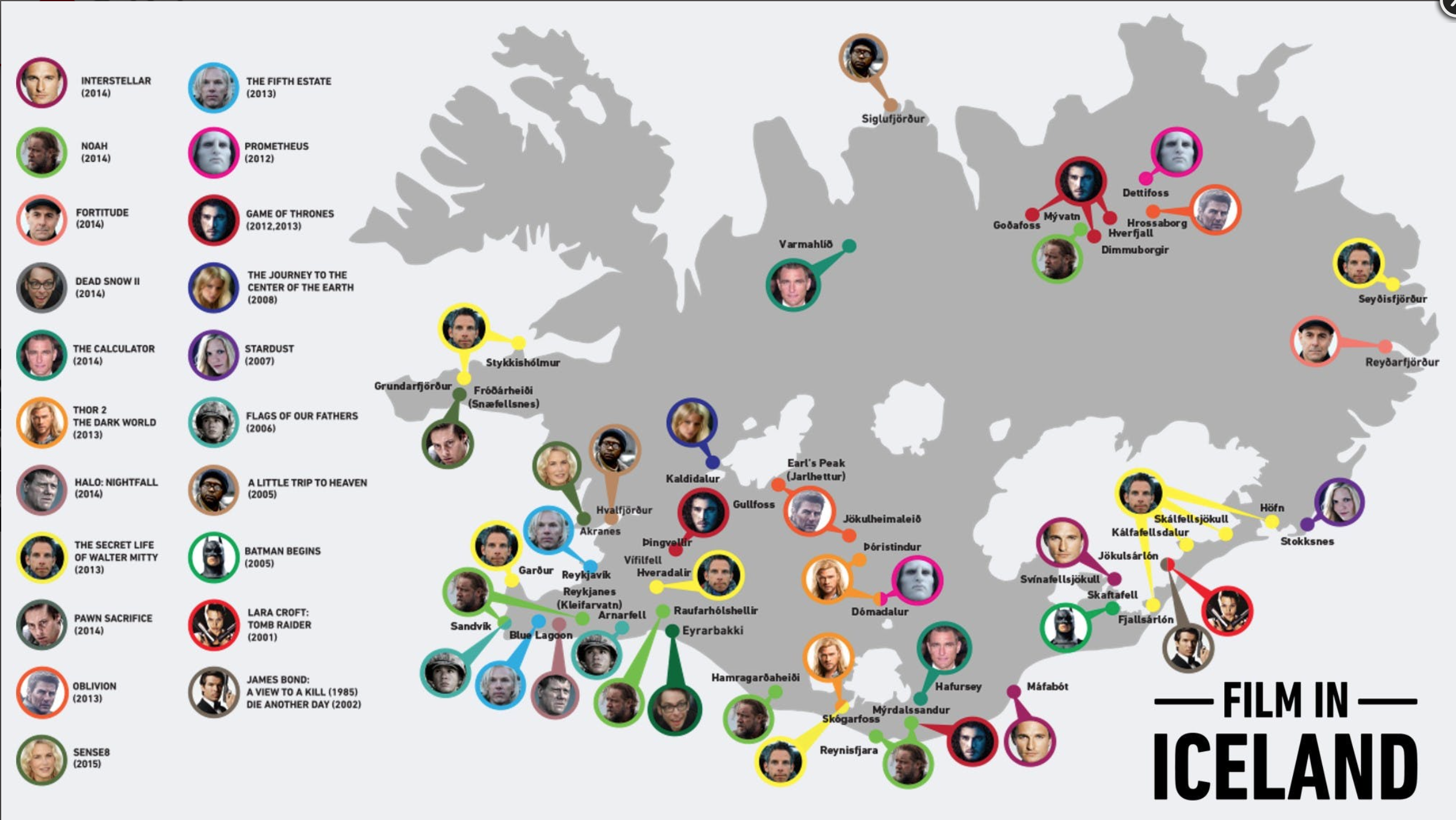

In recent years, Iceland has become a popular choice for film locations. Most notably, the Game of Thrones series was filmed in several iconic landmarks such as Þingvellir national park and lake Mývatn. Other well-known movies such as Intestellar, Thor 2 and Oblivion are all set in outer space where weather conditions are extreme. According to this chart from Guide to Iceland, most of the filming took place after 2010 (Chart)(Film in Iceland, 2018). This could be due to a combination of the Nattura environmental concert, and the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull. Nevertheless, this has brought Iceland’s landscapes into the world of popular media, which has since contributed to tourism for the country. In Grjótagjá, otherwise better known as the Jon Snow Cave, it was originally only used by locals under the permission of the owner. However, now the site is overrun with tourists. There are signs set up to prevent people from bathing in it. The increase use of Iceland as film sites provided context for tourists to visit.

Tourism campaign – Inspired by Iceland

Other than Iceland’s presence in popular media, the government also contributed to romanticizing the landscape. Due to the Eyjafjallajökull eruptions in 2010, the government used this as an opportunity to launch a special marketing campaigned known as Inspired by Iceland. They invested 350 million ISK to push content through “viral marketing, Facebook, Twitter and other social media” platforms (Benediktsson, 2010). Many people were excited to see the ashes looming over the country, and perhaps using this experience to feel more like an “inhabitant” of Iceland (2010). Iceland had turned their extenuating circumstance around with a successful marketing strategy.

In the early years, Iceland was exposed to popular media through literature and music by Icelandic artists. After the eruptions in 2010, Iceland appeared more in films and started catching international attention. Alongside with the Icelandic government’s tourism campaign, it is not a surprise that the country has built their reputation by the romanticized notion of pristine wilderness.

Bibliography

Battaglia, Andy. “Back to Iceland: The Náttúra Environmental Concert.” Music. August 23, 2017. Accessed June 17, 2018. https://music.avclub.com/back-to-iceland-the-nattura-environmental-concert-1798214329.

Benediktsson, Karl, et al. “Inspired by Eruptions? Eyjafjallajökull and Icelandic Tourism.” Mobilities, vol. 6, no. 1, 22 Dec. 2010, pp. 77–84., doi:10.1080/17450101.2011.532654.

Gunnarsdóttir, Nanna. “Movie Locations in Iceland.” Guide to Iceland. June 23, 2015. Accessed June 17, 2018. https://guidetoiceland.is/history-culture/movie-locations-in-iceland.

Incentives. Accessed June 17, 2018. https://www.filminiceland.com/incentives/.

Ingram, Annie. “Coming into Contact.” Thinking of Our Life in Nature, 2007, 1-14.

Jones, Lucy. “Radiohead, Björk, Dylan: 12 Beautifully Poetic Lyrics about Nature.” NME. September 04, 2017. Accessed June 17, 2018. http://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-blogs/radiohead-bj-rk-dylan-12-beautifully-poetic-lyrics-about-nature-762548.

Magnason, Andri Snær. “Anarcho-surrealism Thrives.” The Effects of Poverty on Children on JSTOR. June 01, 2013. Accessed June 9, 2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41963171.

GristTV. YouTube. July 07, 2008. Accessed June 17, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqXooEZSPGA.

Shannen, Lisa Gail. “Inspired by Iceland.” Reykjavik.com. June 26, 2012. Accessed June 18, 2018. http://www.reykjavik.com/inspired-iceland/.