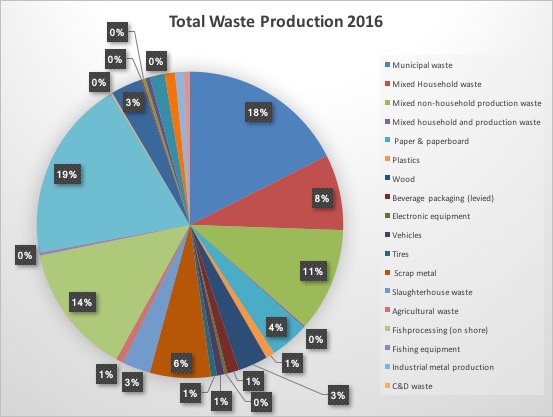

After learning about plastic waste treatment in Iceland, I had a few more unanswered questions. When I examined the issue further, it turns out that plastic waste only makes up 1% of waste in Iceland. The two source that tops waste production are industrial metal production and municipal solid waste, making up 19% and 18% respectively (Statistics Iceland, 2016). While plastics are an important issue to tackle, I am interested in understanding the overall waste management policy on the two biggest sources of waste in Iceland.

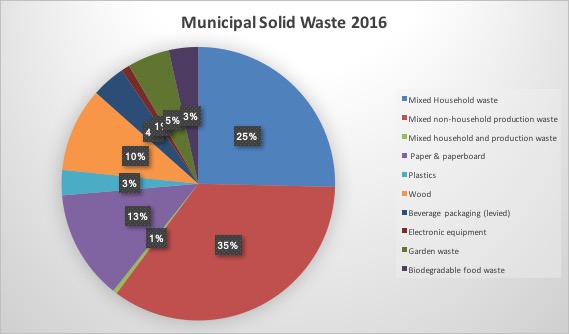

Municipal solid waste indicate waste produced by the public. This includes household and non-household wastes. Within these two sources, non-household wastes dominate by making up 35% of the MSW. While household wastes follow closely behind with 25%, the bigger issue seems to be pointing towards businesses. According to the European Environment Agency, most of the MSW is landfilled in Iceland (EEA, 2013). Out of the 174,000 tonnes of MSW produced in 2007, 67% of that was sent to the landfill (2013). Prior to 2000, open-pit trash burning was the most common solution. Comparing to how it used to be dealt with, landfilling almost seem like a step up from such practices. In the 33% of waste remaining, 17%-23% was reported to have been sent for recycling in 2008 (2013). The rest was incinerated. It is important to note that due to Iceland’s remote location and smaller size, there is a lack of recycling facilities nationally such as paper mills, plastic facilities, and glass works. This is due to the low and dispersed population of the country, making it difficult and expensive to facilitate a nationwide recycling scheme. The main source of waste that is recycled locally is biodegradable wastes.

As for industrial metal production, we’ve learned from our visit to ALCOA aluminum smelter that they try to recycle most of their materials. The more well-known waste would be the anodes that are changed very frequently. They are made up of carbon and used as a conductor in the process of smelting. Other than anodes, the largest amount of industrial metal production waste is SPL and dross (Gunnarsson, 2016). Spent Pot Linings (SPL) must be replaced every 5-7 years. The pot lining is particularly difficult to treat because contact with water or acid will result in toxic gases such as hydrogen fluoride, ammonia, phosphine and methane. Hence, SPL is banned from landfill in America to prevent toxic leakage into soil (2016). The other source of waste is dross, which is the resulting oxides and nitrides on the surface of molten aluminum. This by-product contains 50% metallic aluminum, making it just as hard for after treatment like SPL (2016). Not only do they produce flammable and toxic gases when contacted with water, they are expensive for transport and cannot be kept outdoors. If exposed to the outdoor environment, they will form ammonia clouds. Hence, they are usually treated with salt on site to separate aluminum from impurities. This result in salt cakes that sent to UK for treatment along with SPL and carbon anodes.

In both scenario, waste that is recyclable are exported and processed elsewhere. Therefore, the country’s focus is on waste prevention, especially for biodegradable waste as it is the main source that is processed locally. As we’ve learned from the group presentation on plastic, a waste prevention programme was launched in 2016. The objectives are listed as “reduce waste generation, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve use of resources…” (EEA, 2016). Through learning about the treatment of two of the biggest sources of waste in Iceland, I’ve come to realize that exporting industrial and some municipal waste elsewhere, the country could maintain the image of a sustainable nation. While they are sustainable in many aspects such as clean energy, there is room for improvement when it comes to waste management. Comparing to other Nordic countries such as Norway and Denmark, they only send 0.7% to 2.5% of MSW to landfills (Hafstad, 2016). However, both countries burn trash for energy generation.

I believe waste prevention was the right step to take for Iceland in tackling their waste management. As Brynhildur Davidsdottir pointed out in her lecture, Iceland is a wasteful nation with an ecological footprint of 2.8 hectares per person (Davidsdottir, 2018). Even though some waste is exported elsewhere for recycling, Iceland shouldn’t ignore this problem.

Bibliography

Fischeer, Christian. Municipal Waste Management in Iceland. PDF. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency, February 2013.

Gunnarsson, Guðmundur. Recycling of Waste from the Primary Aluminium Industry. PPT. Reykjavik: Reykjavik University Seminar on Aluminium, Energy and Environment, April 7, 2016.

Hafstað, Vala. “Half of Household Waste in Landfills.” Iceland Review. March 09, 2016. Accessed June 17, 2018. http://icelandreview.com/news/2016/03/09/half-household-waste-landfills.

European Environment Agency. Iceland – Waste Prevention Programme. PDF. European Environment Agency, October 2016.