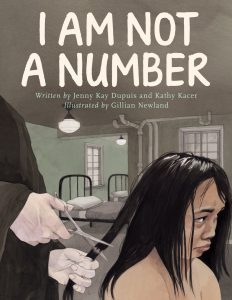

Source: Second Story Press, Jenny Kay Dupuis & Kathy Kacer/Gillian Newland

While ASTU 100 has allowed students to explore a number of themes and works, this post has given me the opportunity to offer another work that I believe would extend the knowledge of life narratives for my peers and I. My nomination is I Am Not a Number by Jenny Kay Dupuis and Kathy Kacer, with illustrations by Gillian Newland. There are a number of reasons for this selection, but for the purposes of this post I will break it into three key points: the target audience, subject matter, and relation to other works in the course.

This is a picture book based on Dupuis’ grandmother’s experience in the residential school system in Canada. The narrative follows Irene as she and her brothers are forcefully removed from their home, before being separated upon arrival at the school. There she becomes subject to abuse and neglect, while simultaneously having her identity stripped away from her; she cannot speak her mother tongue and is only referred to by the number 759.

This is a powerful trauma narrative that targets an audience that has not been addressed in ASTU: children. We have had many discussions about the influence of genre and intended audience on life narratives, however studying the presentation of trauma to children would allow us to analyze through a different theoretical framework. We would have the opportunity to discuss the sharing of childhood trauma with an equally young audience, while additionally discussing the role the illustrations play in the narrative.

Source: Second Story Press, Jenny Kay Dupuis & Kathy Kacer/Gillian Newland

The second reason I believe we should study this work is because of the content of the story itself. The residential school system is an important issue that needs to be addressed, especially considering the location of our institution on the unceded land of the Musqueam peoples. It is our responsibility as guests to educate ourselves about the injustices that have been imposed on the Indigenous peoples of our nation. By studying this book, we will be given the opportunity to further our knowledge of Indigenous issues that will spark necessary conversations on these difficult subjects.

Finally, I believe this picture book would compliment the work that has already been done in the course. As previously stated, I Am Not a Number is based off the experience of the grandmother of one of the authors. This lends itself for comparisons to be made to Forgiveness by Mark Sakamoto, a memoir that shares the stories of the author’s grandparents during World War II. Both narratives have a responsibility to both their relatives and their audience to authentically share the traumatic experience. Additionally, the discussion of race would compliment Missing Sarah by Maggie De Vries, a memoir that prompts discussions of contemporary Indigenous discrimination. The following discussions of Indigenous rights also correspond with the archival studies done in the course, particularly the online archives of residential schools. In the archives the narratives are shaped by those in power, but this book would provide an alternative view of the experience.

It is for these reasons, I believe that the powerful story of I am not a Number deserves a place on the ASTU 100 syllabus.