Final Maps

After completing labs on a bi-weekly basis for most of the term, GEOB 270 required that students form small groups in order to complete several maps and form a report, without the step-by-step guide that we had grown accustomed to. Our main goal was to assess the biogeographical and social features of the Agricultural Land Reform (ALR) region of Okanagan Similkameen. Even though ALR land is meant to be restricted for agricultural purposes, much of this l and is currently being used for non-farm purposes. These include uses such as roads, golf courses and reserves. Our project goal was to highlight these areas in order to have a better understanding of how the ALR land is being used.

In regards to project management, the members of my team (Andrea, Daniel, Stephanie) and I discussed which sections of the project we would like to work on. Daniel and Stephanie decided that they would prefer to create the biogeographical maps and analysis, while Andrea and I preferred the social. For other sections of the report, such as the Executive Summary and Further Research sections, the group ensured that these parts were equally distributed.

As a team member, I believe that my most value contribution to the team was the amount of work that I put into the maps for the social analysis of the Okanagan Similkameen ALR. I was attentive and careful in choosing the appropriate layers, colours and symbols for each map. I would also like to draw attention to the work of my partner for the social section, Andrea. She was always willing to help myself and other group members and was exceptionally attentive to the formation of the report.

As a result of completing this project, I learned a tremendous amount about ALRs, GIS techniques and tips for project management. Before this assignment, I had never heard of ALR land. It was interesting to learn about its existence and its complexity, especially concerning its relationship to indigenous reserves. My capacity related to GIS techniques has also improved significantly over the duration of this class. One of the most important things that I learned was that it only takes one small move to make a mistake in ArcGIS. Because of this, it is crucial to be attentive and take breaks if you need to. Lastly, I experienced the invaluableness of documenting the tasks for each group member. Even if all members are attentive to the project, it acts as helpful tool if anyone forgets their assigned tasks.

The following is the report for the Similkameen Okanagan ALR Region:

A Case Study and Analysis of Agricultural Land Reserves in the Similkameen Okanagan Region, British Columbia, Canada

Andrea Lucy, Nicole Rich, Daniel McFaul & Stephanie Glanzmann

Term 1 – GEOB 270

Lab L1C

Teaching Assistant: Eva CregoLiz

December 7th, 2015

Table of Contents

Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.1

Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………p.1-2

Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………p.2

Biogeographical Section………………………………………………………………………………………………………p.2-4

Social Section……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.4-7

Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………p.7-8

Errors and Uncertainty………………………………………………………………………………………………………p.8-9

Further Research/Recommendations………………………………………………………………………………..p.9

Appendices………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………p.10-22

References…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.10

Data Sources……………………………………………………………………………………………………….p.10-11

Maps…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.12-19

Okanagan Similkameen Agricultural Land Reserve Map…………………………………………………p.12

Biogeographical Maps

Okanagan Similkameen Land Cover………………………………………………………………….p.13

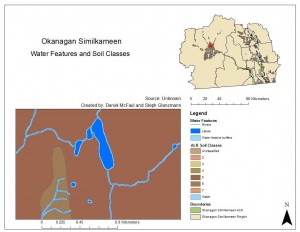

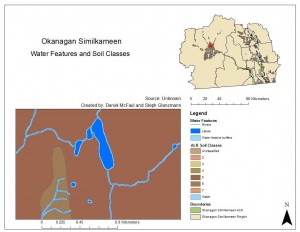

Okanagan Similkameen Water Features and Soil Classes………………………………….p.14

Okanagan Similkameen Slope & Agricultural Productivity…………………………………p.15

Social Maps

Okanagan Similkameen Road Types…………………………………………………………………p.16

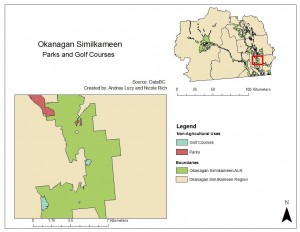

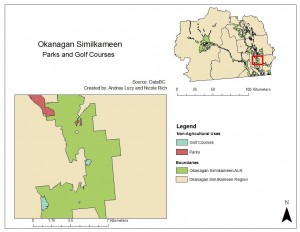

Okanagan Similkameen Parks and Golf Courses………………………………………………p.17

Okanagan Similkameen Non-agricultural Social Land Uses………………………………p.18

ALR Final Analysis Map………………………………………………………………………………………………….p.19

Flow Chart………………………………………………………………………………………………………….p.19-21

Division of work …………………………………………………………………………………………………p.21-22

Executive Summary

This project analyzes the state of the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) system in British Columbia, with a focus on the Okanagan Similkameen census division. An indepth look is taken into the biogeographical and social uses of the land that currently is considered ALR land, but should not be. ArcGIS and its many data analysis functions were applied to TRIM data and government data to refine and highlight relevant features.

Analysis shows that that there are a wide variety of agricultural protective restrictions that are not respected in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR, such as roads, buffered water features, and unsuitable farmland. These are non-agricultural uses, therefore the accuracy of how much land under protection is compromised. This in turn poses as a problem to food sovereignty issues, developing land management plans and providing accurate food production data.

An overarching issue that has been identified is that there is a lack of organization within management of the Agricultural Land Reserves, and it’s ability to address flaws in the current structure.

This project faces some limitations as there was potential for error (human, statistical, etc.) at every point of analysis, as is explored in the report.

Introduction

There has recently been concern about whether British Columbia’s Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) laws are being respected. The ALRs, zones restricted for agricultural purposes, were originally created in the early 1970s to address the worry that “prime agricultural land” was being increasingly developed (Provincial Agricultural Land Commission, 2014). As of March 2015, it has been noted that nearly 100,000 hectares of ALR land is not being used for it’s intended industry (Provincial Agricultural Land Commission, 2014). However, these numbers are estimates because there had not yet been a thorough calculation and analysis of mis-used ALRs.

This analysis uses ArcGIS software to investigate the biogeographical and social non-agricultural features in the ALR of the Okanagan Similkameen region. The primary purpose of this report is to determine the amount of land that is truly being used for agriculture uses according to the ALC Act and ALR Regulation, and what features are falsely considered ALR areas (Provincial Land Commission, 2014). The results will be disseminated through open sources, therefore available for public consumption. The hope of this report is that it will help inform public debate and provide a more accurate calculation related to ALR land in British Columbia.

As previously stated, the study area for this report is the census division of Okanagan Similkameen. This is area is in southern British Columbia bordering with the United States (see Map 1). The largest city in the region is Penticton with a population of approximately 32,000 (Penticton, n.d).

The data used was collected by different provincial government or federal government ministries, including DataBC and Statistics Canada. They cover both social and biogeographical thematic features. ALR areas were provided by Arthur Green (2015), the creator of this specific project. The data used was believed to be credible and trustworthy. The Okanagan Similkameen area is covered by two National Topographic 250k map sheets, 92H and 82E that had to be merged for analysis. For this entire analysis, the data and map projection was NAD 1983 BC Environment Albers using a geographic coordinate system of GSC North American 1983.

Overview

Specifically, the study area is the Agricultural Land Reserves estimated to cover 83,923.35ha, 4% of the Okanagan Similkameen region (see Map 1). This calculated area was created using GIS and published on April 1, 2014 (Provincial Agricultural Land Commission, 2014, p. 31). The features in the ALR area were split into two categories for analysis: biogeographical and social. In preparation for an analysis of these two uses with ArcGIS, all of the thematic vector and raster layers were first clipped to the ALR project boundary (see Flow Chart).

Biogeographical Analysis

Land Cover

There are 4 types of land cover in the original ALR shapefile; annual cropland, perennial cropland, developed, and unclassified. This data was sourced from the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (2015). Once the data was added as a layer, it was separated into its land use categories through processes using the attribute table (see Map 2).

| Land cover |

Total Area (ha) |

% of Okanagan Similkameen ALR |

| Annual Cropland |

498.65ha |

0.6% |

| Perennial Cropland |

1949.82ha |

2.3% |

| Developed |

1616.60ha |

1.93% |

| Unclassified |

356.24ha |

0.42% |

Table 1. Types of landcover and area (ha) in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR project area.

Water Features

The bodies of water that are included in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR analyses were rivers and lakes. The data sources for each were from BCGOV ILMB Crown Registry and Geographic Base Branch (2015). Though watersheds and water sources are intrinsic to the viability of agricultural land, their total shape area should not be considered usable ALR land. Both lakes and rivers were buffered by 10 m to maintain riparian ecosystem health. Rivers and lakes and were unioned for future analysis of water features. The dissolve function was used to fluidly join points of intersection. Including the buffered area, water covers 4,445.61ha and accounts for 5.3% of the total Okanagan Similkameen ALR (see Map 30.

Soil Types

The ALR uses a ranking system from 1-7 where soil type 1 is extremely arable, and 7 is virtually unusable (Agricultural Land Commission, 2013). Soil types found within the Okanagan Similkameen ALR boundaries are type 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, W, and unclassified (see Table 2; see Map 3; Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 2013; Ministry of Environment, 2015). There were concerning dataless sections of the soil layer, but these are different from the ‘unclassified’ soils.

| Soil Types |

Total Area (ha) |

% of Okanagan Similkameen ALR |

| 2 |

854ha |

1% |

| 3 |

501ha |

0.6% |

| 4 |

7,135ha |

8.5% |

| 5 |

33,442ha |

40% |

| 6 |

12,408ha |

14.7% |

| 7 |

5,285ha |

6.3% |

| Water |

767ha |

0.9% |

| Unclassified |

2,081ha |

2.4% |

Table 2. Soil types and the area (ha) they occupy in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR project area.

Slope

It has been identified by Hermansen and Green (2015) that few agricultural activities can occur on land that has a slope greater than 30%. In order to see how much land falls into this category, the raster DEM data was reclassified into two categories, above 30% and below 30% (Government of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Earth Sciences Sector, Mapping Information Branch, GeoAccess Division, 2012). The above 30% was then extracted as a new raster layer and converted to vector data (see Map 4). It covers an area of 7,061.58ha and accounts for 8.41% of ALR land.

Agricultural Products

The 2011 Agricultural Census data gathered by Statistics Canada (2011) provides general insight into the types of agricultural production and frequency of agricultural activities. There is diversity in the type of agricultural production conducted in Okanagan Similkameen ALR. Among food crop products, fruit, berries and nuts has 5,511ha devoted to it, making it the most abundant agricultural use category (Statistics Canada, 2011). Other agricultural activities present within the region are hay and field crop production, livestock rearing, and vegetable production (see Map 4; Statistics Canada, 2011).

Social Analysis

Roads

There are several types of roads that crossed all throughout the Okanagan Similkameen region. Although important for transportation of agricultural resources, nothing can be grown on these roads. The roads data was acquired from BCGOV ILMB Crown Registry and Geographic Base Branch (2015). The summary statistics function was used to calculate the sum of the length of clipped roads, which was 2564.576km. There are 10 types of roads that make up this figure:

| Type |

Length (km) |

| Gravel Road 1 Lane |

497.29km |

| Gravel Road 1 Lane Under Construction (U/C) |

1.16km |

| Gravel Road 2 Lane |

197.88km |

| Overgrown Road |

1.04km |

| Paved Road 1 Lane One Way |

0.02km |

| Paved Road 2 Lane |

667.74km |

| Paved Road 2 One Way |

6.52km |

| Paved Road 3 Lane |

0.44km |

| Paved Road 4 Lane |

8.05km |

| Rough Road |

1185.19km |

Table 3. Road types and their length (km) in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR project area.

When categorizing these road types to represent on maps, they were arbitrarily generalized to 4 types based on construction material for reader accessibility: Gravel Road; Overgrown Road; Paved Road; Rough Road (see Map 5).

In this report, roads also occupy space on either side because of the inability to grow close to the roads (Hermansen and Gill, 2015). Our analysis acknowledged this concern by creating a buffer of 10m. The area attribute of this new buffered layer was summed to reveal that 5,093.97ha or 6.07% of the original subpanel ALR is covered by roads and their accompanying buffer.

Parks & Golf Courses

Parks are another area in the ALR that are not directly linked to agricultural practices, therefore are not part of the ALR area. The attribute table of the clipped parks layer showed that the feature categories are ‘provincial’ and ‘other parks’ (see Map 6). ‘Other parks’ include Ecological Reserves and Protected Areas.

Another green space in the ALR that is not used for agricultural purposes are golf courses. This was part of the cultural infrastructure data layer, acquired from BCGOV ILMB Crown Registry and Geographic Base Branch (2015). The select by attribute query was used to create a new layer of solely golf courses. The resulting layer was represented in polylines. To determine the area of each golf course, this layer was transformed using the ‘feature to polygon’ function. A new layer was created from this process named golfcourse_polygon and the summary statistics function was used to determine the entire area it occupies (see Map 6).

| Feature Type |

Area (ha) |

| Total Parks |

1,574.14ha |

| Provincial Parks |

84.76ha |

| Other Parks |

1,489.38ha |

| Total Golf Courses |

238.05ha |

Table 4. Area (ha) occupied by parks and golf courses in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR project area.

Population Demographics

The Okanagan Similkameen region is a federal census division, therefore the 2011 Census survey data from Statistics Canada (2013) was used to analyze the social makeup of the region. In 2011, there were 78,385 people living in the area. There were more females, 40,605, than males, 37,790 at the time. 76,130 of the residents were Canadian citizens, conversely 2,265 people were not. Of these Canadian citizens, 12,585 are under age 17. The average family size in 2011 was 2.7 people. The region is ethnically diverse, based on the 2011 census categories used in this report. The most represented ethnicities are listed below, but this is not a complete list of all the ethnicities in the area:

- British Isle origins: 43,945

- North American Aboriginal: 5,900

- North American other: 18,235

- French origins: 8,975

- Western European origins: 19,410

- Visible minority: 4,395

Additional Social Non-Farm Uses

There are a number of other cultural infrastructures in the ALR region that are not used for agricultural purposes. These include pipelines, transmission lines, fences, rail lines, pits, dumps, and reserves, all of which was acquired from BCGOV ILMB Crown Registry and Geographic Base Branch (2015; see Map 7a & 7b). They were all in the clipped cultural infrastructure layer, therefore a select by attribute query was used to select each specific infrastructure from the attribute layer, creating a new polyline layer. The other layers created from the cultural infrastructure layer had to undergo further data management processes. The pits and dumps were transformed from a feature to a polygon to be able to calculate the area they consume. A separate reserves layer, acquired in polygon form, was used to calculate the area they cover in the project area.

| Feature |

Total Area (ha)/Total Length (km) |

| Pipelines |

110.39km |

| Transmission Lines |

134.17km |

| Fences |

41.95km |

| Rail lines |

127.1km |

| Pits |

74.30ha |

| Dumps |

21.24ha |

| Reserves |

12,506.36ha |

Table 5. Non-farm uses and the area (ha) or length (km) they occupy in the Okanagan Similkameen ALR project area.

Major Social Threats to the ALR

Based on this analysis, we think that the most common socially created threats to the Okanagan Similkameen subpanel region are reserves, roads, and parks. A key issue is that while reserves are federally administered land controlled largely by the preferences of the indigenous peoples living in it, ALR land is provincially administered. The issue is that much of the reserve land in the region researched overlaps with the ALR region, when the two should not cross each other. The reason for this is that reserve land is not inherently used for agricultural purposes. The federal reserves cover 19.4% of the ALR region. It is apparent that this overlapping was not examined during the ALR program creation in the early 1970s (Runka, June 21, 2006).

The roads cover 6.07% of the ALR and fragment the agricultural land. Parks cover 1.88%. However, in regards to parks, conservation parks fall into Section 3(1) of the ALR Regulation, making them a permitted use even though they are not directly linked to agriculture. An area for future research is to determine if some of these ‘other parks’ may fall into this permitted use category.

Overall, man-made features such as roads, parks, golf courses, reserves, pits, pipelines, transmission lines and dumps do cover a large area of the currently designated ALR land in the Okanagan Similkameen region. Consequently, much of this area is not being used for it’s intended purpose of agricultural activities.

Summary

The thematic layers analyzed that are not used for agricultural purposes, yet were officially part of the ALR, were erased to provide a more accurate representation of how much usable agricultural land is in the Okanagan Similkameen region. After erasing the layers identified in Table 6, the total ALR land calculated in this analysis is 54,061.31ha. This is only 64.42% of the official total area of ALR land in the region.

| Feature |

Area(ha)/Length(km) |

| Slope >30° |

7,061.58ha |

| Soil Class 7 |

5,285 ha |

| Parks |

1,574.14ha |

| Golf Courses |

238.05ha |

| Pipelines |

110.39km |

| Reserves |

12,506.36ha |

| Dumps |

21.24ha |

| Pits |

74.30ha |

| Transmission Lines |

134.17km |

| Rail |

127.1km |

| Roads & buffer 10m |

5,093.97ha |

| Fences |

41.95km |

| Water (lakes & rivers) & buffer 10m |

4,445.61 |

Table 6. Non-farm uses and their area or length that was erased from the original Okanagan Similkameen ALR area to produce a more accurate calculation of useful agricultural area in the ALR.

There is huge discrepancy between this final calculation, 54,061.31ha, and the total area of the original dataset. Of even more concern is that this number does not match the Agricultural Land Commission’s (2013) 1974-1975 calculation that there was 86,478ha of ALR land in the Okanagan Similkameen upon creation (Provincial Agricultural Land Commission, 2014, p. 31). Based on this large discrepancy, the current estimates of hectares calculated by the Agricultural Land Commission are not accurate and are in need for official policy revision.

Error and Uncertainty

As with any GIS analysis, this analysis of the Okanagan Similkameen ALR is not free from error. Errors may have arisen from data quality surrounding. There may also be inherent errors in the data used. Although the data was acquired from trustworthy sources, such as Statistics Canada and DataBC, that does not mean it is always complete. For instance, the numbers in the the Stats Canada 2011 Census Survey did not always add up to total population in the area, as in the case with ethnicity. Some of the data used was also incomplete, as in the case of the land cover and soil datasets that did not have values for the entire region. Additionally, some of the data was captured decades ago, such as the TRIM data from 1992 and the DEM data from November 15, 2002 (BCGOV ILMB Crown Registry and Geographic Base Branch, 2015; Government of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Earth Sciences Sector, Mapping Information Branch, GeoAccess Division, 2012). Data captured more recently would be more precise, and would avoid any changes in the landscape that have occurred since these older dates. As a result of these errors and uncertainties, the results are not as accurate or precise as may be desired.

Being new users to ArcGIS and geographic information systems in general, a major source of error could be in the data analysis. It is possible that steps were missed or performed incorrectly as the data was analyzed and transformed.

Some errors and subjectivity were unavoidably included in the representation of the maps. Personal preferences came forth in conceptual selection of symbology colour gradients that were used to show differences in our data. Additionally, some of the features used are generalized on the maps by being categorized. For instance,the roads were simplified by the map creators into 4 categories. Although useful to the reader for understanding the maps, it does reduce the level of detail. The maps also have error in them in regards to scale. For instance, the roads are actually much smaller in reality than they appear on the map, but they have been enlarged so that they are visible. Due to this issue, the measurements included in this report are a valuable tool in conjunction with the maps for understanding the true scale. This is important as our map may be used in a future decision-making process surrounding ALR in the Okanagan Similkameen region.

Further Research and Recommendations

This report is just a preliminary start to the research that should be done on the ALR in the Okanagan Similkameen region. It must be acknowledged that this data analysis is incomplete as it does not include every possible feature that could be studied. Therefore, this analysis is a generalization of only a few of the issues affecting ALR land laws. For instance, mines, sewage areas, and campsites could be included in future analyses. Buildings are one such vector point that were not included in this study, but are important. No dataset was found that detailed the functions of the buildings in the region, which is important because according to the Provincial Agricultural Land Commission (2014), some buildings are a permitted use of the ALR. Having included the building datasets acquired into the maps would have introduced unnecessary error.

In regards to some of these features, such as pipelines, fences, and transmission lines, a buffer is suggested to be researched and included in the future. There may be a certain buffer distance considered along these polylines for safety or due to an inability to grow along these lines.

A recommendation to policy makers and the Agricultural Land Commission is to carefully consider this discrepancy in calculations between the estimated and actual ALR, and implement policies that can better protect and manage the land. As well, they should consider how these land changes even occurred, to prevent them from happening again.

Although this analysis could be improved upon in the future, this report provides a starting point. It provides an idea of how much land currently considered ALR in the Okanagan Similkameen region is not used for agricultural purposes or appropriate uses.

Appendices

References

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2013). Overview of Classification Methodology for Determining Land Capability for Agriculture. Retrieved December 6, 2015 from http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/cli/classdesc.html

Agricultural Land Commission. (2013). Agricultural Capability Classification in BC. Retrieved from http://www.alc.gov.bc.ca/assets/alc/assets/library/agricultural-capability/agriculture_capability_classification_in_bc_2013.pdf

Hermansen, S., & Green, A. (2015). Final Project. Retrieved December 6, 2015, from https://blogs.ubc.ca/giscience/final-project/

Heywood, I., Cornelius, S., & Carver, S. (2011). An introduction to geographical information systems (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Green, A. (2015). GIS analysis case study: BC agricultural land reserve discussion. [PowerPoint slides].

Letnick, Norm. (2015). Provincial Agricultural Land Commission: Annual Report (2014/2015). Burnaby, British Columbia: Provincial Agricultural Land Commission.

Penticton. (n.d.) Demographics. Retireved December 6, 2015 from http://www.penticton.ca/EN/main/business/economic-development/about-penticton/demographics.html

Provincial Agricultural Land Commission. (2014, June 30). Annual Report 2013/2014. Retrieved from http://www.alc.gov.bc.ca/assets/alc/assets/library/commission-reports/2013-14_alc_annual_report_final_revised.pdf

Provincial Agricultural Land Commission. (2014). Permitted uses in the ALR. Retrieved December 6, 2015 from http://www.alc.gov.bc.ca/alc/content/alr-maps/living-in-the-alr/permitted-uses-in-the-alr

Runka, G. (2006, June 21). BC’s Agricultural Land Reserve – Its Historical Roots. Retrieved from http://www.alc.gov.bc.ca/assets/alc/assets/library/archived-publications/alr-history/alr_historical_roots_-_runka_2006.pdf.

Data Sources

BCGOV ILMB Crown Registry and Geographic Base Branch. (2015). Terrain Resource Information Management Program – (TRIM) Version 3 (Data file). Retrieved November 23, 2015 from http://hdl.handle.net/11272/10166

Government of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Earth Sciences Sector, Mapping Information Branch, GeoAccess Division. (2012). Canadian Digital Elevation Model Mosaic (CDEM) (Data file). Retrieved November 23, 2015 from http://geogratis.gc.ca/api/en/nrcan-rncan/ess-sst/C40ACFBA-C722-4BE1-862E-146B80BE738E.html.

Green, A. (2015). ALR. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Vancouver. Retrieved November 23, 2015 from https://www.dropbox.com/sh/55y487zz8hs6m32/AADV9awhjk_8C42kKg_jLtbLa?dl=0

Ministry of Environment. (2015). Agriculture_Capability (Data file). Retrieved November 23, 2015 from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/esd/distdata/ecosystems/Soil_Data/AgricultureCapability/

Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. (2015). Other Land Cover 1:250,000 GeoBase Land Cover (Data file). Retrieved November 23, 2015 from http://catalogue.data.gov.bc.ca/dataset/other-land-cover-1-250-000-geobase-land-cover

Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. (2016). Indian Reserves — Administrative Boundaries (Data file). Retrieved November 23, 2015 from http://catalogue.data.gov.bc.ca/dataset/indian-reserves-administrative-boundaries

Statistics Canada. (2013). Okanagan-Similkameen, RD, British Columbia (Code 5907) (table). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa. Released September 11, 2013. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Statistics Canada. (2011). Table 004-0221 – Census of Agriculture, cattle and calves on census day, every 5 years, CANSIM (database). Retrieved from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=0040221&pattern=004-0200..004-0242&tabMode=dataTable&srchLan=-1&p1=-1&p2=31