The growing human rights catastrophe in Myanmar has been on my mind.

Eidomeni, Greek-Macedonian border

Just last March, I was working with the Médecins Sans Frontières team, UNHCR, Save the Children and other smaller grassroots organizations to provide urgent humanitarian relief to the 16,000 refugees, mainly from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, who were stuck in the borders after the EU had announced the closure of the Balkan borders. In fact, underneath the more obvious desire to learn about the refugee crisis firsthand was a deeper and more personal reason: To better understand my own family history — and what it was like for my grandparents to flee as refugees from Burma during the Second Sino-Japanese War in the 1940s.

Today, in an oddly circular way, the world’s attention is on Myanmar — a country that does not typically get much attention — and its treatment towards the Rohingya population.

The Situation: What is happening?

“I call on the government to end its current cruel military operation, with accountability for all violations that have occurred, and to reverse the pattern of severe and widespread discrimination against the Rohingya population.” – Zeid Ra‘ad al-Hussein, United Nation’s High Commissioner for Human Rights

On Monday, September 11, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, United Nation’s High Commissioner for Human Rights condemned Myanmar’s brutal military operation against the Rohingya a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” There are reports of ethnic cleansing, villages being burned, mass rape and executions on the Rohingya, an ethnic Muslim minority group who live in the Rakhine state of Myanmar (a Buddhist majority country).

https://www.facebook.com/ajplusenglish/videos/1048973808577459/

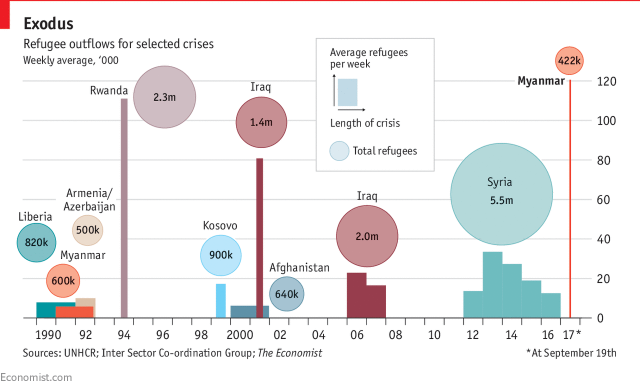

More than 400,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to the Bangladesh borders in the recent weeks. According to the chart by The Economist, the weekly outflow of the Rohingya refugee has been the highest since the Rwandan genocide.

The Roots: How did it begin?

The Current Crackdown

The current military campaign was triggered by an armed attack on border police by Rohingya militants on August 25. The Rohingya militants, mostly armed with knives and crude implements, killed 12 police officers. Though armed Rohingya insurgents exist, their numbers are overall small, and they are poorly equipped.The indiscriminate and brutal response by the military has disproportionately affected the entire ethnic group.

Although a speech delivered by Aung San Suu Kyi on September 19 has promised to allow the Rohingyas to return, there are further reports about the military laying landmines near the Bangladesh border to prevent the Rohingya from returning.

The Waves of Violence

However, this would not be the first time the government has launched an ethnic cleansing campaign towards the Rohingya. The Rohingya Muslim minority has been persecuted and disenfranchised for decades.

According to Human Rights Watch, Operation Nagamin in the late 1970s drove out more than 200,000 Rohingya; and in the early 1990s, more than 250,000 Rohingya fled Myanmar for Bangladesh trying to escape rape, violence, and forced labor.

Oh, Colonialism (You did it again)

In fact, the tension and antipathy towards the Rohingya could be traced to the country’s colonial roots, when the Rohingya minority sided with the British colonialists, according to Azeem Ibrahim, author of The Rohingya: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide. When Myanmar gained its independence from the British colonialism, the feeling within Burma that the Rohingya are leftover guests during the Colonial era, continues to persist, creating a deep sense of resentment between ethnic groups (Muslim/Buddhist) that is not unlike in Rwanda (Tutsi and Hutu) or between the Palestine/Isreal.

Further Thoughts: On the Historic Disenfranchisement of the Rohingya Minority

There is a longstanding history of disenfranchisement and persecution towards the Rohingya Minority. This hatred is a product of specific political (colonial) choices that has become a widespread resentment between ethnic groups.

In Myanmar, even the word “Rohingya” is a taboo. Instead, the Rohingya are referred to as “Bengali”, a slur that labels them as foreign implants from Bangladesh. This deep sense of resentment between ethnic groups (Muslim/Buddhist) is not unlike that in Rwanda (Tutsi/Hutu), Iraq (Sunni/Shia), and in between Palestine/Isreal.

Although Myanmar’s first real election in 2015 was lauded as a major step forward for democracy from a military dictatorship, the situation of the Rohingya did not improve at all. Their language is still banned, they cannot get a marriage license, there is a mandatory two-child limit policy, they can’t travel between villages, and their citizenship was stripped in Myanmar’s 1982 citizenship law, leaving them without access to healthcare or education. The ethnic segregation has caused fragmentations which led to an upsurge in violence.

What does this say about the situational design of Myanmar that claims to be a democracy? Do democratic norms and values only apply to some people and not for others?

Eidomeni make-shift refugee camp

The propinquity of witnessing the depths of social injustice that exists in the world has left me with a deep commitment and conviction to continue this work, and in many ways, has led me to pursue the path I am taking right now. Yet, there have been (and still are) pockets of moments when I wonder: To what extent? To what extent can we stop this? How can the international community stop the internal sociopolitical hatred that has led to mass persecution and genocide of people? More economic sanctions – the typical option against military government and dictatorship that has worked so well for North Korea? What happens next? The conflict in Syria still persists under the watchful eyes of the world.

And perhaps it is moments like this, that I am reminded of my last night in Eidomeni. I sat around a campfire, and one of my refugee friends asked me: “Nicole, do people care that this is happening?” It was a simple question that left me unexpectedly stupefied.

I find myself coming back to this question again and again. And simple enough: I care. And I know – I have seen – many others who care as well.

Final Thoughts and Some Recommendations

Although the situation in Myanmar is very complex, I do believe there are things that could be done to mitigate some of the horrors.

To the Government of Myanmar

- Stop the violence.

- Amend the 1982 citizenship law to grant citizenship for the Rohingya and grant full and equal citizenship rights of the Rohingyas

- Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, State counselor of Myanmar and international icon Aung San Suu Kyi has been widely condemned for her equivocal and lukewarm position on this issue. Although Aung San Suu Kyi does not and cannot control the military, the widespread dislike for the Rohingya minority in the Burmese society is where I think she does have a role to play in but is failing at. To stop the systemic social and economic disenfranchisement of the Rohingya that led to the unfolding of the humanitarian crisis, a broad cultural shift and understanding. This is a space and place where Aung San Suu Kyi’s power and leadership will be very useful in.

- Commit to a process of reconciliation and allow meaningful opportunities for the Rohingya population to integrate into the society

To ASEAN

- Follow Bangladesh’s example to provide support and aid to the Rohingya refugees fleeing from terror and violence

Canada’s role (and the International Community)

- There is opportunity for Canadian diplomacy to palliate the situation by pressing the Government of Myanmar to fulfill its responsibility to protect the people of Burma

- Provide greater humanitarian support and aide for the Rakhine State, Bangladesh, and neighboring countries taking in and aiding the Rohginya

Further Reading

The history of the persecution of Myanmar’s Rohingya (The Conversation)

Ongoing Abuses and Oppression of the Rohingya in Myanmar (Refugee International)

“No one told me I was going to be interviewed by a Muslim”: Aung San Suu Kyi’s Rohingya problem (Vox.com)

Myanmar’s Rohingya Refugee Crisis, Explained (Bloomberg QuickTake)

Aung San Suu Kyi, a Much-Changed Icon, Evades Rohingya Accusations (The New York Times)