1.1 Introduction

In the fall of 2011, a social phenomenon sprung into existence in New York City, capturing the imagination of millions, and inspiring many more to rethink what was possible. But although Occupy Wall Street is distinct and novel in many important ways, is also firmly rooted in the legacy of social uprisings that have preceded it. Much like prior pushes for change, Occupy is a popular reaction to political and economic agendas which, as far as its participants are concerned, have enhanced the station of domineering interests, while exacerbating the plight and diminishing the voice of marginalized groups in society. What’s different about Occupy, however, is its scope; the movement is broad-based, diffuse and inclusive. Rather than serving a limited, easily identifiable constituency, or set of interests, OWS claims to represent the interests of the majority, and the collective pursuit of liberty, democracy, opportunity, solidarity, community. As the movement’s mantra goes: “We are the 99 per cent.”

1.2 Neoliberalism, globalization, and corporatism

The goals and passions of protesters who have joined the Occupy movement are diverse, from preserving biodiversity, to ending corporate personhood, to denouncing the proliferation of nuclear energy, to acknowledging the impact of the colonial legacy on Aboriginal people. But inchoate as these objectives appear to be, there is a common thread that intertwines nearly all of them: the ideology of neoliberalism that emerged from the University of Chicago in the 1970s, the distinctive form of political economy it has produced, and its awkward, rankling rescue from the jaws of death, beginning in 2008, through an historic bequest of corporate welfare.

In The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism, Prof. Colin Crouch of Warwick University describes the ideology and the economic model it has produced, and investigates why it failed to perish—or at least to suffer a rightful loss of credibility among the political elite of the developed world—in the wake of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. The primary consequence of neoliberalism, as Crouch illustrates, has been a growth and consolidation of corporate power. By extension, other societal consequences, like the criminalization of dissent and the despoilment of natural resources, have followed.

As the name suggests, neoliberalism is (at least superficially) a revival of many ideas espoused by classical liberalism, a mindset that emerged in the enlightenment salons of post-revolutionary France, and later evolved in 19th-century Britain and the United States. Liberalism’s earliest proponents favoured the laissez-faire approach to most questions, emphasized the promotion and protection of egalitarianism and civil liberties (at least for white men), and, importantly, lauded the virtues of economic and commercial freedom. Among the ideological architects of free-market liberalism were David Ricardo and Adam Smith, the latter of whom espoused the belief that markets would lead to equilibrium, fair working conditions, accurate pricing and distribution of goods and services, under conditions of perfect liberty (that is, unimpeded by state intervention or other forms of coercion). To Euro-American societies in the throes of a bloody exodus from the tyranny of monarchs and empire, the idea of a diminished role for the state, and the freedom of the individual to choose, held understandable appeal.

Neoliberalism—a revival of the liberal notion that free markets offer fairness and the efficient distribution of wealth and resources better than market interventions ever could—experienced a dramatic surge in the 1970s, concomitant with a string of important historical events: the 1971 decision by U.S. President Richard Nixon to detach the U.S. dollar from the last vestiges of the gold standard, which led to the implementation of fiat money in global finance, and the installation of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency; and an extended period of “stagflation” in the United States, the consequence of an economic recession (which produced high unemployment) contemporaneous with a pair of oil shocks in 1973 and 1979 (which, along with the abandonment of the gold standard, the sudden annulment of Nixon’s price controls, and the unpaid debts the U.S. government accrued through the Vietnam War, produced dramatic and sustained inflation). It was in this context of a mounting “misery index,” that the ideas of economists Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman—both opponents of government intervention in the economy, the welfare state, social programs, and the fiscal stabilization approach advocated by John Maynard Keynes—began to garner more widespread appeal. Beginning under President Carter, and accelerating under President Reagan, sectors of the American welfare state first constructed under Franklin Roosevelt, and expanded under Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, began to be dismantled. This dismantlement has continued in the years hence, while similar neoliberal conceptions have come to dominate the political economy of Canada, Europe, Russia, India, Brazil, China, and most of the world’s developing countries.

Under Reagan, one of neoliberalism’s inevitable consequences arose, as wealth disparities between the poorest and richest Americans began to rapidly broaden. Crucially, Reagan further broke from tradition by trampling America’s long-standing antitrust regulation, designed to prevent large firms from gaining too much market share (Crouch, 54-55, also noted in Klein No Logo, 163). (The iconic president Theodore Roosevelt, among other Republican stalwarts, had been a staunch proponent of suchlike regulation in his day.) Reagan’s decision laid the groundwork for global “competition,” which forms the intellectual basis of capitalism, to achieve its logical end—corporations began to expand, merge, and dominate ever-increasing market shares, enhancing their own scope, reach, and earning potential, while effectively reducing consumer choice. Neoliberalism’s stock continued to rise throughout the 1980s (it had been credited, however dubiously, with bringing an end to the 1970s stagflation through savage cutbacks to public services), into the 1990s and eventually the 2000s, with stark results for both public policy and society as a whole. Free trade agreements like NAFTA created further means and incentives for corporations to cut costs and maximize revenues by shipping manufacturing jobs overseas, sub-contracting to foreign factories, and seeking out countries and markets wherein infrastructural needs and demand for labour, technology and components could be met, but also wherein environmental and safety regulations were laxest, taxes and wages lowest, and labour unions severely restricted or non-existent.

A further consequence of this process has been the increasing influence of multinational corporations and their owners and executives—most of whom were once American, but now owe allegiance to no nation—over the political landscape of the nations and jurisdictions in which they do business. Political leaders, anxious to attract investment, “capital” and private-sector jobs, have played along with the amoral profit- and rent-seeking mission, slashing taxes and dismantling public programs to reduce corporate expenses—an approach Western political euphemists, who lack the authority to impose forced labour and outlaw collective bargaining as totalitarian states like China freely do, describe as “enhancing competitiveness,” “controlling spending,” “fiscal discipline,” and “creating a ripe environment for job creation.”

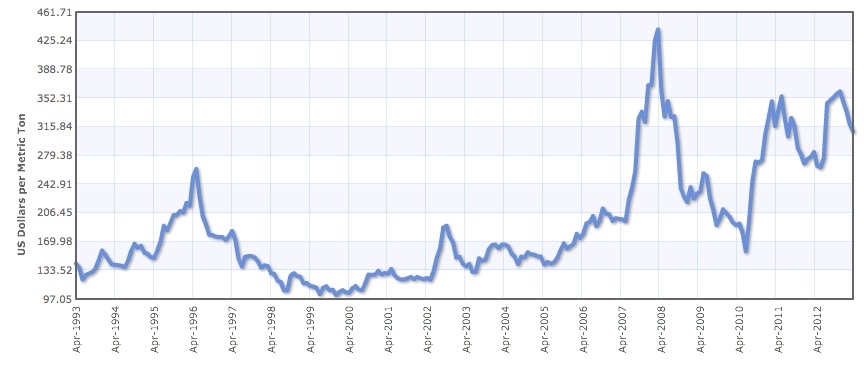

The race-to-the-bottom mentality of globalization and so-called free trade, political corruption, the infamous Citizens United ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court, a burgeoning (and increasingly villainous) financial sector in Western countries whose constituents subsume ever larger capital flows while imposing ever more burdensome debt loads (Hudson, 1998) and occasionally even bet against their debtors’ ability to repay, a sharp decline in manufacturing, union membership and middle-class jobs in the West, and the persistence of a neoliberal orthodoxy on the policy agenda despite its failings, have combined to inflict numerous socially undesirable outcomes. For instance, the climate change denial movement largely consists of propaganda and pseudo-science from a fossil fuel industry anxious to maintain and expand its profits. All the while, climate change and ocean acidification continue their steady march toward the point of no return.

Deregulation, often spun as “cutting red tape,” leaves an increasing expanse of the natural environment and Indigenous territory unprotected, resulting in unprecedented loss of biodiversity and destruction of both natural and human assets. “Free” trade, idolized by Reagan, Thatcher, Mulroney, and Clinton, has facilitated a reduction in consumer prices for many imports, offset by a migration of middle-class jobs from the wealthy countries to overseas destinations like China, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Bangladesh (Fletcher, 2010).

1.3 Responses to corporatism

Much has been written about popular responses to the increasing influence of corporations within the public sphere. Within this body of literature, Naomi Klein’s No Logo distinguishes itself from the work of Crouch and others, by contending that neoliberalism and corporatism have not necessarily been determined by a growth in the sheer scale of the multinational firms themselves, but rather, by the prominence of the brands and marketing identities they seek to promote.

Klein argues that as corporations like Nike, Reebok, Apple and Microsoft have invested greater sums in their public image, partly owing to advances in communications technology, they’ve sought to reduce direct expenditures on the manufacture of products. This has led many large firms to outsource labour not only to foreign countries, but to foreign subcontractors (in an arrangement which resembles, for instance, Apple’s business relationship with China’s FoxConn Corporation). The consequence of this behaviour is that while logos, corporate images, insignia and advertising play an increasingly influential role in developed countries, the size and payroll of the firms themselves have not increased to nearly a commensurate degree. Rather, multinationals place orders with their subcontractors, who guarantee delivery of a given stock of product at a specified price, by an agreed-upon deadline. To achieve this, subcontractors and their suppliers exploit workers, bar collective bargaining and unionization initiatives, and confine much of their activity to export processing zones (EPZs), or free trade areas, in which most taxes, fees, tariffs and labour regulations do not apply. Among the examples Klein cites is the town of Rosario, in the Philippines, where an EPZ provides the majority of the community’s employment, but simultaneously undermines the growth of its economy by paying poverty wages, underselling local competitors and contributing next to nothing to Rosario’s treasury.

Klein describes various forms of activism in opposition to this model of corporate profiteering that have evolved since the 1960s, including “culture-jamming,” or altering advertising and corporate logos to reveal social ills like anorexia among fashion models, third-world worker exploitation, or rainforest destruction by chocolate producers in search of palm oil; consumer activism and online knowledge-sharing around products and where and how multinational firms conduct their business, the potential for which has exploded in the age of the Internet and social media; and “street parties,” or large social gatherings in the 1990s (and later the 2000s) with a view to simultaneously reclaiming public spaces, and denouncing corporate overreach. All of these ideas have had a significant impact on the Occupy movement—it was culture-jamming magazine Adbusters that first called on activists and concerned citizens to occupy Wall Street, while the constant exploitation of workers and the environment by multinational firms is among the movement’s chief grievances, and the desire to reclaim public spaces from private interests has motivated Occupy activists across the Western world to pitch tents and stay a while.

1.4 The global economic crisis, disillusionment, and the impetus for Occupy

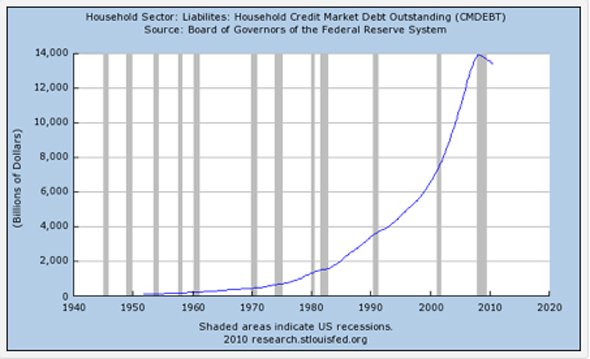

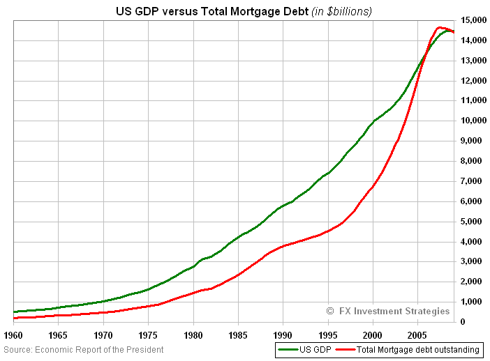

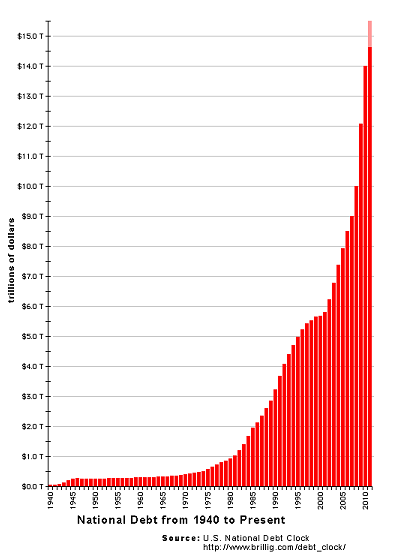

Ballooning inequality and the diminution of the middle class, cutbacks to public services like higher education and social transfers, unscrupulous predatory lending tactics by oversized financial institutions, and the introduction of credit cards and increasingly complex financial instruments, have all contributed to an unprecedented spike in consumer credit and household debt since 1980. (According to the Bank of Canada, our country’s gross domestic product has grown roughly fivefold since then, while consumer credit has increased tenfold.) It was a fraud of repackaged, falsely-advertised subprime mortgage debt that precipitated the economic collapse of 2008, a crisis mitigated only through recapitalization of the culpable institutions by befuddled federal administrations. Politicians, some of whom (like current U.S. President Obama) received generous campaign contributions from these same institutions, were (at least ostensibly) faced with two unsavory options—nationalize the monstrous banks and dissolve them into smaller, localized institutions to promote a long-term structural economic recovery, or accord them loan guarantees from the federal coffers on few, if any, conditions.

Conscious of the fickleness of their electorates, benefiting from the support of their wealthy bidders, and limited to brief terms in office, politicians nearly unanimously chose the latter option. As a result, billionaire bankers have been spared both judicial reprisals and the justice of market discipline, as their too-big-to-fail banks (and obscene publicly-collateralized salaries) further enlarged through the crisis. Meanwhile, multinational corporations, having whiled away the recession by paying down debts, laying off workers, outsourcing, offshoring and automating more jobs while successfully ducking state taxation, have watched their profits soar to record highs.

At street level, on the other hand, the economic recovery has been anemic, characterized by low-paying and increasingly precarious jobs, and accompanied by further public-sector cutbacks, bankrupted municipalities, and disintegrated pension funds. A post-crisis race-to-the-bottom mentality has also sparked a money creation and currency devaluation contest among the large economies, and has demanded continual, frequently draconian austerity measures, especially in Europe, but also in the U.S., Canada, and other developed nations. Recent history suggests there is method in this madness, however; to borrow the primary concept of Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, in many jurisdictions, the financial crisis has become a weapon of politicians and business interests, who have capitalized on popular disarray in the wake of the 2008 meltdown, and consequent federal budget deficits, to implement a project of accelerated government service reduction, privatization and deregulation—a sort of rocket-propelled neoliberalism.

Spain and Greece, who unwittingly relinquished their monetary and fiscal autonomy with the adoption of the Euro in 1999 and 2001 respectively, have been victimized most severely by the cutbacks, and transformed most rapidly and perilously by the subsequent neoliberal marketization. But Canada, the U.K. and the U.S. have also suffered austerity to varying degrees, while our leaders have resorted to the familiar neoliberal program of deregulation, crippling cuts to government programs deemed unimportant, privatization, corporate welfare, resource exploitation, systematic undermining of labour union authority, artificially sustained asset bubbles, and copious political propaganda.

The above factors, along with the general impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators of the crisis, and a media establishment that often appears to disproportionately represent the interests of the elite, served to elevate the rightful indignation of the citizenry to a fever pitch by the summer of 2010. Public dismay erupted in the form of the G-20 protests in Toronto, the largely misguided U.S. Tea Party movement, the student-led demonstrations in England, the Indignados of Spain, the Arab Spring uprisings of the Middle East and North Africa, labour protests in Madison, Wi., and eventually Occupy Wall Street. (The student-led Printemps Erable of 2012 and The Idle No More movement of winter 2012-13, while distinct from their antecedents, are both reactions to different aspects of the same neoliberal process.)

1.5 The tenor of a movement

Occupy Wall Street began as a hodge-podge of dissatisfied citizens, united primarily by their dissatisfaction, but not necessarily in the issues they sought to confront, nor the potential solutions (if any) they hoped to advance. It’s no coincidence that “Hey hey, ho ho, the status quo has got to go!” quickly became a signal chant of the uprisings—clear and unambiguous, but sufficiently generic to encompass Occupy’s wide-ranging discontent and diverse participants. There were some notions upon which the protesters managed to reach broad consensus, however: namely, that the wealth disparity in America and other Western nations was escalating out of control; that affluent lobbies had ingratiated themselves in the halls of power, to the detriment of the general public; that an economy built on debt peonage, the quest for perpetual growth and unchecked environmental exploitation was unsustainable; and above all, that corporations were not persons.

Todd Gitlin, a veteran of protest movements and political activism since the 1960s, is well placed to offer commentary around the long legacy of civil dissent that forms the foundation for the Occupy movement. In Occupy Nation, he offers a reasoned, eloquent and informative perspective focused on the New York uprising, its precedents and sources of inspiration, and what may lay ahead for the movement.

Although the occupation of Wall Street on September 17, 2011 would have appeared spontaneous to most outside observers, Gitlin notes that organizers had begun to plan the congregation months in advance. Adbusters editor Kalle Lasn issued his “call to occupy,” along with the post-script “Bring a tent,” on June 9. On June 14, a group of anti-austerity protesters established “Bloombergville” in Zuccotti Park—a tent village inspired by the Hoovervilles of the 1930s, which held daily general assemblies during its brief lifespan. By September 17, the Twitter hashtag #occupywallstreet had spread like wildfire; social media thus became, in a way reminiscent of the Arab Spring uprisings and Iran’s 2009 election protests, a redoubtable vehicle for sharing information among activists and observers, a forum by which organizers could coordinate their plans, sympathizers, share and reaffirm their grievances, and political thinkers, expound on the causes they hoped to champion.

While many Occupiers complained about the “media blackout” their movement suffered in the early going, Gitlin argues the contrary, a position corroborated by communications specialist Bill Dobbs of the Occupy PR Working Group (1: 16/21). But even though, as Dobbs contends, news reports abounded, Gitlin notes that quality and fairness of representation was frequently lacking. One of the first analytical news articles on the Manhattan encampment came from Ginia Bellafante of the traditionally liberal New York Times on Sept. 23, 2011—under the headline “Gunning for Wall Street, with Faulty Aim.” In a manner consistent with much of the early Occupy media coverage, Bellafante’s piece portrayed the movement as disorganized, dominated by “hippies” and fringe elements, intellectually vacuous, and lacking in clarity, articulacy, coherence and leadership. As Gitlin writes:

Disparagement and incomprehension were not hard to derive from news media who were drawn to the most garish and photogenic sights in the encampment, the outré and the scruffy, with their scatter of protest slogans, their anger at capitalism, their general disrespect, their apparent disorder (Preface, 3/4).

Considering the dismissiveness of many early media critiques of Occupy, the staying power of the movement must have come as a surprise to some journalists and policymakers. Soon, President Obama and others began to not only acknowledged the movement’s legitimacy, but attempted to co-opt its message for their own political purposes. The president, in particular, was keen to exploit Occupy as a sort of “liberal answer” to the Tea Party movement, by resurrecting the rhetoric of American wealth disparity, and insisting that multinational corporations and the country’s moneyed minority “pay their fair share” and “play by the same set of rules” (Scherer, 2011).

However, to ascertain the attitude of Occupiers toward the White House, it’s crucial to acknowledge the Obama administration’s perpetuation of and expansion upon the virulently illiberal policies of his predecessor (thoroughly examined in feminist cultural critic Naomi Wolf’s The End of America)—including state surveillance, impunity for members of the corporate and governmental elite, contrasted with ferocious law enforcement and soaring incarceration rates for the laity, escalated drone warfare, contravention of civil liberties, corporate cronyism, expanded “free” trade, environmental laxity, and friendly-faced austerity. Meanwhile, the gulf between rich and poor has widened under Obama’s watch, just as his signature healthcare law afforded a handsome and practically inescapable windfall to profit-driven medical insurers. For the president to take for granted the support of the Occupiers would be more than presumptuous, as demonstrated by the fervent protests at last year’s Democratic Party Convention in Charlotte, N.C. In reality, the U.S. Occupy movement is largely a reflection of disillusionment toward the commander-in-chief and the powerful interests he represents, rather than implicit support for his agenda, which many Occupiers would characterize as no more than the lesser of two evils (Gitlin, 1: 19/21).

1.6 The general assembly

Many aspects of the process and manner of organization characteristic of Occupy—the General Assembly; “twinkling” and “de-twinkling” one’s fingers to display approval or disapproval; horizontality; the cacerolazo (also prominent at the Printemps Erable protests); and consensus-based decision making—owe their origins to prior social movements and established institutions (Gitlin, 4:1-10, Kaufmann, 47-49, Sitrin, 8-10). Others—like the “Human Mic”—originated within Occupy itself, arising from a need for non-electronic vocal amplification in keeping with a New York city noise bylaw (Gitlin, 4: 1/10). In due course, these tactics spread, disseminated through the use of social media, to sister Occupations throughout the continent and the developed world.

Occupy’s encampments are deliberately designed to represent microcosms of a more collectivist, more sustainable society, of the sort Occupiers hope will prevail in the future. Over the course of their presence in public spaces, Occupy encampments have developed their own models of political economy and division of labour, their own libraries and places of learning, their own methods of resource allocation and citizen engagement. Participants in the Occupy movement aspire to an ideal of cooperative living, consensus-based decision-making, sustainability, egalitarianism, a robust and accessible public commons that encourages the sharing of ideas, and the prioritization of “people before profit.” (These ideals are echoed by longtime activist, professor and political theorist Noam Chomsky in his eponymous Occupied Media pamphlet.) But the Occupy sociopolitical model has not been without its challenges, setbacks and regrets: laborious general assemblies that tested Occupiers’ patience and commitment to the consensus approach; the incidence of problems from the wider world, like male sexual violence against women, drug and alcohol abuse, homelessness, racism, and petty crime; painful but necessary confrontations arising from various forms of privilege (Maharawal, 37-39); police crackdowns and mass arrests; chilly and inclement weather that seemed to beg the question of Occupiers’ commitment to their cause.

1.7 Christopher Hedges’s indictment of unrestrained capitalism,

and reason for hope

One of the most prominent, vocal and consistent supporters of the Occupy movement to emerge from the U.S. media establishment is journalist, author, and former New York Times war correspondent Christopher Hedges. In the non-fiction opus Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt, which he co-authored with veteran political cartoonist Joe Sacco, Hedges articulates a scathing critique of unfettered capitalism and its destructive consequences—or, in the parlance of economics, negative externalities.

Among the problems Hedges explores is the persistent economic inequalities along racial lines that have plagued America since the days of slavery, and that have increased post-crisis. Indeed, a disproportionate number of victims of the subprime mortgage fraud, and subsequent home foreclosures, were African-American, Hispanic, and other members of historically marginalized groups; by contrast, the investors and executives who have reaped the benefits of the profit-seeking mentality, easy credit, preferential loans and inflated home values are disproportionately white. Hedges also investigates the de facto debt slavery of Mexican undocumented migrants (many of whom are farmers impoverished by the combination of NAFTA and American corn subsidies) in Immokalee, Fl.; mountaintop strip mining in West Virginia; and the abject poverty of the Oglala Lakota people at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The picture he paints of America’s prospects, and by extension, the trajectory of the global economic system, is grim:

The decline of America is a story of gross injustices, declining standards of living, stagnant or falling wages, long-term unemployment or underemployment, and the curtailment of basic liberties, especially as we militarize our police. It is a story of the weakest forever being crushed by the strong. It is the story of unchecked and unfettered corporate power, which has taken our government hostage, overseen the dismantling of our manufacturing base, bankrupted the nation, and plundered and contaminated our natural resources. Once communities break down physically, they break down morally (69).

However, Hedges provides reason for optimism in the book’s final chapter, describing the Occupy movement in its incipient stages as “a revolution,” and revolt against the established order as “our only hope”:

There comes a moment in all popular uprisings when the dead ideas and decayed systems, which only days before seemed unassailable, are exposed and discredited by a population that once stood fearful and supine. This spark occurred on September 17, 2011, in New York City when a few hundred activists, who were easily rebuffed by police in their quixotic attempt to physically occupy Wall Street, regrouped in Zuccotti Park, four blocks away. They were disorganized at first, unsure of what to do, not even convinced they had achieved anything worthwhile, but they had unwittingly triggered a global movement of resistance that would reverberate across the country and in the capitals of Europe. The uneasy status quo, effectively imposed for decades by the elites, was shattered (226).

What the new world order Occupy activists hope to construct would look like is unclear, but the unanimous opinion of Occupiers, along with the movement’s supporters, is that the status quo is not working; the corporate-dominated neoliberal economic system, while churning out desirable consumer products in mind-boggling quantities and enriching a privileged few beyond reason, entails environmental and human costs too unconscionable and devastating to bear.

1.8 Winter 2011, and the dissolution of the occupations

Gitlin and others identify many of the myriad vulnerabilities to which the movement began to succumb by the winter of 2011. Popular sentiment soured in some cities, as locals tired of the inconvenience posed by the encampments, and the cost to taxpayers of daily police monitoring. The weather grew colder, compelling some less hardy Occupiers to depart, and eliciting ridicule from unsympathetic ideologues on Fox News, Sun News, and at the National Post. Confirmed reports of sexual assault and sexual harassment of women emerged from the Zuccotti encampment (Resnick and Taylor, ed. by Taylor et al., 187-188). General Assemblies, operating on the basis of horizontality and consensus, were wont to descend into tedium and frustration. The number of homeless and drug-addicted—many of them victims of the same neoliberal, corporate system in the protesters’ crosshairs—began to increase, engendering both internal conflict, and a popular perception of the movement as unhygienic and undesirable (Gluck and Herring, ed. by Taylor et al., 169). In the case of Occupy Vancouver, the tragic passing of 23-year-old Ashlie Gough by drug overdose provided the pretext for the tent city’s court-ordered eviction in November of 2011. Strife arose in Oakland and elsewhere, as protesters debated the merits of non-violence, versus the embrace of a “diversity of tactics”—a euphemism for physically fighting back against economic violence and police crackdowns (Schneider, ed. van Gelder, 39-45). In the same vein, “Black Bloc” protesters—a menacing faction that has aroused heightened suspicion from activists since black-clad undercover police officers posed as agents provocateurs at a 2007 union protest in Montebello, Qc.—began to wreak havoc on store windows and private property, inviting belligerent police intervention. By the winter of 2011, for various reasons and justifications, most of Occupy’s tent cities had been uprooted.

1.9 Shortcomings of the available literature, and whither

Occupy from here?

Due to its novelty, the Occupy movement proper has generated scant literary treatment. However, the same cannot be said of the historical precedents that nourished it—among others, the civil rights and anti-war protests of the 1960s, anti-nuclear activism in the 1970s and ‘80s that continues to the present day, LGBT rights marches, movements for universal suffrage and women’s reproductive freedoms, Mexico’s Zapatista rebellion, anti-authoritarian cacerolazos in Argentina and Chile, general strikes, student strikes, anti-corporate, anti-globalization and anti-austerity uprisings, and labour union unrest across the Western world. From many of these past events, Occupy has borrowed pieces of its own intellectual scaffolding; this is why some examination of the history of protest movements is necessary, in order to glean a thorough and cogent understanding of Occupy’s roots.

The literature examined in this review presents primarily an unsympathetic view of the global socioeconomic system in its current form, but it’s worth noting that this system is not without advantages; as mentioned previously, multinational corporations have succeeded in producing desirable, useful products at modest prices, which ostensibly benefits the deal-seeking Western consumer. The ingenuity facilitated by corporate investments in research and development has produced modes of interpersonal communication and technological advances beyond the wildest dreams of our ancestors. High-level competition between corporations has also enabled the production of new and more powerful tools; Samsung and Apple persist in their efforts to one-up each other in the smart phones market, which can only result in further breakthroughs and enhancements to our way of life. And it’s undeniably true that such competition could not exist absent some form of competitive market discipline, if not pure market freedom. The personal ingenuity of entrepreneurs, like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, has enabled them to attain spectacular wealth, while introducing valuable new tools to our civilization. Even newfangled financial instruments, like credit-default swaps, complex derivatives, mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations, may one day become safer, more effective means of capital allocation, helping the economy to prosper and distribute resources more effectively.

That said, however, there is no law of nature which dictates that capitalism is the only means by which to achieve prosperity while encouraging ingenuity and personal initiative, or that these aims cannot be accomplished more ethically and sustainably than they are at present. And while the free market extolled by neoliberal theorists excels at price discovery and rooting out inefficiencies, it fails catastrophically at mitigating the externalities of unfettered capitalism, preserving elements of “social good” which markets may fail to reflect, and averting the logical consequence of competition—the oligopolistic consolidation of corporate power that has come to dominate the world economy, and much of the world’s popular media, at the time of this writing.

Another unavoidable shortcoming of the extant literature around the Occupy movement, is its lack of discussion of ongoing Occupy projects. In the time since the publication of the works cited in this review, the movement’s physical presence has largely dwindled, but its intellectual, activist fervour endures in the form of the Strike Debt/Rolling Jubilee endeavour—a lottery designed to relieve distressed debtors of their burdensome obligations; the Occupy Sandy project, which seeks to distribute aid to residents of the Tristate Area still homeless, or without heat and electricity, in the wake of the devastating hurricane last October; local Media Co-op initiatives that allow valuable but typically unpublished perspectives to enter the public discourse; and numerous evolving movements, discussion groups, and online fora.

While some have expressed pessimism over Occupy’s future, or asserted that the disappearance of the encampments in 2011 heralded the death of the movement (Caplan, 2012), an abundance of evidence supports the notion that Occupy still has an valuable purpose to fulfill, that its presence has already influenced subsequent social movements, like the Printemps Erable and Idle No More, and that the discussion it sparked around wealth inequality, environmental degradation and the scourge of unfettered corporate power, will inform public discourse, discussions of economics, and political theory for years to come.