5.1 Big credit, big deposits, big banks

As the wealth of the employer class surged since the 1970s, bank deposits and credit followed suit.

“In the last 40 years…you’ve had an unparalleled, historic boom, in which the growing productivity of labour accrues entirely to profits, and not at all to wages,” said Wolff.

“This produces two phenomena that explode the financial sector and banks: on the one hand, a vast amount of wealth is created that accrues, in money form, to the employer class…And they put that money in the bank…At the same time, the working class of Americans is basically shattered; the American dream of an ever-higher standard of living is no longer possible with wages that don’t go up. And one of the solutions found by the American working class is to turn to debt, in a way that they had never done before.”

As much as neoliberal apologists like to trumpet the beneficence of the “job creators,” the true engine of the economy is aggregate demand. Producers can generate products and services all they like, but unless a sufficient number of consumers are able and willing to pay for these products and services, producers will be unable to earn a dime, and an economy can’t possibly grow absent an explosion of credit and debt—the likes of which the U.S. and many other countries have experienced in the neoliberal era.

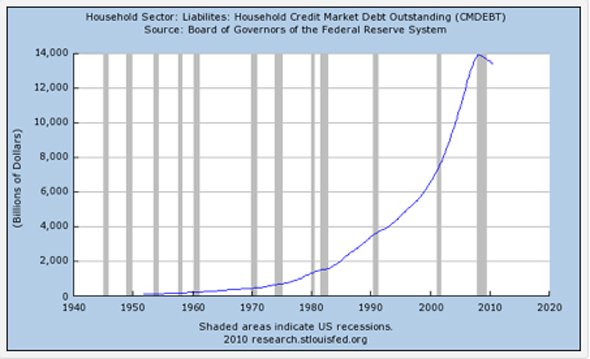

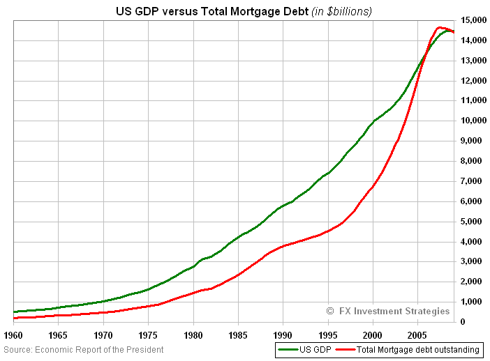

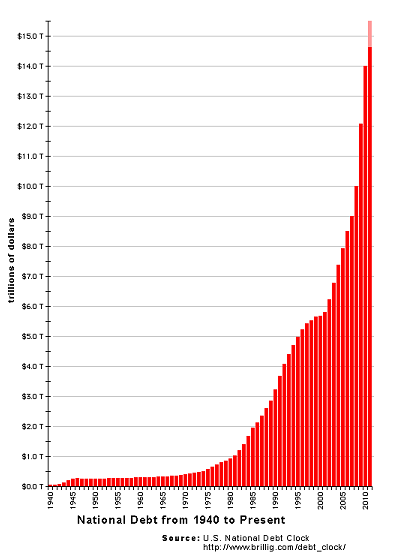

The following charts illustrate

1. total U.S. household credit market debt outstanding, since 1970 (Fig. I);

(Retrieved from St. Louis Fed web site http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/CMDEBT)

2. U.S. mortgage debt compared to GDP over roughly the same period (Fig. II);

(Retrieved from FX Investment Strategies http://www.fxinvestmentstrategies.com/2010_02_01_archive.html)

and 3. U.S. federal government debt, since 1940 (Fig. III);

This spectacular buildup, needless to say, is not sustainable; total debts outstanding in the U.S. economy now exceed the ability of debtors—both public and private—to repay them. This mountain of borrowing combined with the reckless activities of Wall Street institutions that bid up the price of homes through speculation, peddled sub-prime mortgages to clients who would eventually be unable to service them, and then sold or lent toxic liabilities in the form of debt-backed securities (to which credit rating agencies, equally complicit in the crisis, ascribed their highest degree of confidence) to precipitate the 2007-’08 economic crisis.

Ultimately, the cost of avoiding a second Great Depression would have to be borne by someone.

5.2 Foreclosure crisis

Wall Street’s biggest banks enjoyed spectacular profits prior to the 2007-‘08 collapse, before their fortunes temporarily turned sour. In 2009 and 2010, the big banks initiated foreclosure proceedings against millions of American mortgage holders, many of whom were “underwater”—i.e., confronted with a real estate collapse that had reduced the value of their homes to a level below the value of their mortgages. Some of these were landlords or speculators who abandoned ship at the first sign of trouble, leaving hundreds of thousands of residences in the U.S. vacant at a time when homelessness had simultaneously skyrocketed in most American cities. Others had fallen behind on their payments as a result of chronic illness, injury, or unexpected rate hikes imposed by the banks. But there was still another large category: Those who faced wrongful foreclosures, many of whom had never missed a payment. By April of 2013, it was revealed that these completely innocent victims numbered close to 4 million—nearly a third of the total (Nasiripour, 2013).

www.youtube.com/watch?v=exxRes2JiJE

As MSNBC host Chris Hayes explains in the above video, the average settlement Wall Street banks paid to the victims of wrongful home foreclosure amounted to a mere $500, pursuant to subsequent court rulings—seldom sufficient to cover a month’s rent in America’s largest housing markets.

Of course, the air of inevitability hangs over any economy in which private debts escalate to a scale at which repayment—even by the gainfully employed who enjoy consistently good health and manage to avoid unanticipated adversity—nears the threshold of arithmetic impossibility, as it had in the U.S. by 2007. Furthermore, a disproportionate number of mortgage holders who fell victim to the Wall Street banks’ predatory lending practices were people of colour. And according to data retrieved by the Pew Research Center, among individuals whose net worth declined most due to the Great Recession, African-Americans and Latinos—who tend to hold fewer assets on average than their white American counterparts—are also dramatically overrepresented.

Fig. IV

Fig. V

Hence, the catastrophe of 2007-’08 not only revealed in America enormous class divides long concealed by an economy built on hollow, fictitious prosperity; it also made plain what millions of Americans know in their hearts but are still reticent to say: that wealth disparities, throughout the country’s history, have been entrenched along racial lines, that they remain entrenched along those racial lines, and that the American experiment in capitalism has, for all its champions, fallen miserably short of rectifying the injustices of its colonial past.

5.3 Canada at risk?

Incidentally, in Canada, household debt is now at a record high, even higher on a per-capita basis than private debt levels in the U.S. prior to the collapse. And given that inequality in our country has also increased since the crisis, with record numbers of Canadians relying on food banks and a federal government with no apparent interest in addressing the situation (when UN Special Rapporteur Olivier de Schutter issued a report criticizing the state of food security in Canada last year, Immigration Minister Jason Kenney and Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq both chided him for “lecturing a wealthy country”), Canada’s claim to economic stability would appear to be tenuous at best. Household and consumer debt in the country, as of March 2013, totaled more than $1.5 trillion—close to 90% of GDP, and rising.

As research economist and balance-of-payments expert Michael Hudson is fond of saying, “Debts that can’t be repaid, won’t be repaid.” His observations are echoed by Steve Keen, an Australian economist who specializes in the study of the link between private-sector debt and economic recessions—a process called “debt deflation.” In his book Debunking Economics, Keen notes that private-sector debts play an integral role in both precipitating and prolonging economic recessions, but that this connection is still little understood by the majority of neoclassical economists. It is a reality which, in Canada as in most other Western countries, ought to be cause for alarm. And the efforts of the Canadian federal government to balance its budget by 2015, by essentially removing equity from the economy through austerity measures, will only exacerbate the already colossal burden of private indebtedness.

Fig. VI

(Retrieved from Saskatoon Housing Bubble http://saskatoonhousingbubble.blogspot.ca/2011/12/saskatchewans-real-gdp-growth-from-2005.html)

But how did the forces of greed, rent-seeking and excessive credit get so far out of control in modern capitalism? And more perplexingly, why did the 2007-’08 crash not elicit a louder, more profound public critique of the flawed economic system that caused it? How has America—and nearly every other industrialized country, Canada included—simply bailed out its irrationally oversized banks and carried on with a status quo doomed to usher in more pain and suffering for millions in the years to come?

Part of the answer to that question may lie in the disintegration of the constituency that has historically played a prominent role in holding the failings and iniquities of capitalism to account: the left.