7.1 The Arab Spring

Though America (somewhat disingenuously) prides itself on its penchant for upholding liberty and democracy, its policies toward the Middle East and North Africa have tended historically to be inimical with both of these principles. By the beginning of 2010, many allies of the U.S. in the region were draconian strongmen: among others, President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia, Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, and the despotic military ruler of Libya, General Moammar Qaddafi. But on December 17, 2010, a single act of defiance inspired millions of Arabs to take to the streets.

Like so many of his compatriots, vegetable vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, aged 26, was neither an attention-seeker, nor a man in quest of celebrity, opulence or prestige; his objective, according to his aunt, Radia, was to save up enough money to buy a pickup truck, a giant step up from the burdensome, rickety cart he was obliged to haul about, every day, under the burning sun. But when Bouazizi’s vegetable cart was seized by a local policewoman, who proceeded to fine the merchant a day’s salary, spit in his face and insult his dead father, Bouazizi decided enough was enough.

After his attempt to lodge a complaint with the local municipal office was rebuffed, Bouazizi proceeded to publicly douse himself in fuel, and set himself alight. Though he survived his self-immolation, he would succumb to his extensive burns in hospital less than three weeks later. But his solitary protest served as a powerful symbol for his compatriots. They too decided the time had come to demand better than the corrupt autocracy with which they had been saddled for generations. And their rage overcame their fear.

7.2 Wall Street’s role in the Arab Spring

Interestingly, while Wall Street became the target of justifiable ire in the U.S., the impact of the big banks’ misdeeds on what would become the Arab Spring was equally significant.

In the modern economy, digitized capital is far freer than it has been in the past to leapfrog across international borders, owing allegiance to no state. Investors, some of whom have amassed preposterous fortunes by placing bets on the vicissitudes of the stock market, have developed means of gambling on the dollar value—both present and future—of commodities as diverse as gold bullion and seaweed. And in so doing, in pouring their wagers into goods as a collective bloc, these speculators, in turn, play a substantial role in affecting what the final asking price of those goods will be.

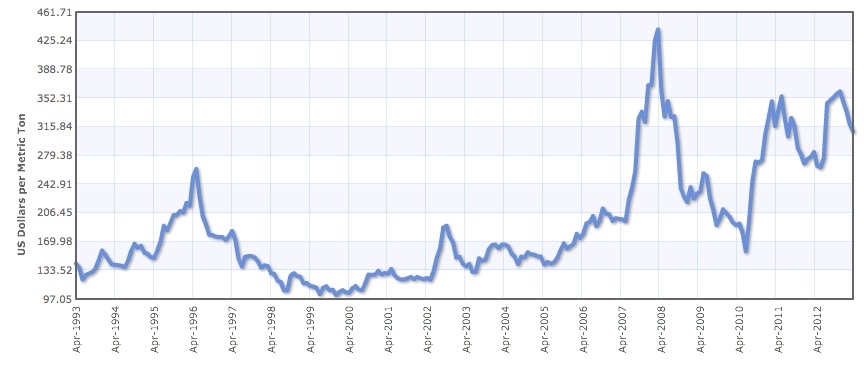

Tunisians and Egyptians are the most substantial per-capita consumers of wheat in the world, and Egypt imports more wheat that any other nation. Its population of over 80 million continues to depend heavily on bread, tabouli and other cereal-based foodstuffs for basic nutrition. But beginning in December of 2010, a price shock struck global food markets, leaving increasing proportions of citizens in North Africa hungry, angry, and desperate. By May of 2011, the price of wheat—and its derivative products—had increased by 91% over the previous year, leaving millions wondering why such an integral staple of their diet had suddenly become inaccessible. Many would have looked to the regimes of Mubarak and Ben Ali for answers and found none. Egyptians had lived with the indignity of dictatorship for decades, and many had opted to maintain a low profile, as their Tunisian neighbours had, to avoid incurring the wrath of their despot’s merciless posses of goons. But the unprecedented spike in the cost of bare necessities was the straw that broke the camel’s back. And it was the manipulations of speculators half a world away, compounding the challenges of severe drought and lower-than-usual crop yields, that made the increase possible.

As the 20th century became the 21st, some of Wall Street’s largest firms—in particular Goldman Sachs—began buying up reams of futures in food staples like wheat, perhaps anticipating that climate change, rising global population and increased government mandates for ethanol and biofuels would send the prices of these commodities skyward. Indeed, the aforementioned factors all contributed modestly to rising prices, but Goldman Sachs et al. became self-fulfilling prophets, inflating an asset bubble for which they themselves provided the fodder. In 2005, a period of decline in the real price of wheat over more than a century on the Minneapolis Grain Exchange abruptly halted, and immediately reversed. By early 2008, a steep upward trend had developed in the price of cereals and soybeans, precipitating a food crisis, and by the end of that year, more than 250 million people had joined the ranks of the world’s famished. Like the U.S. housing bubble, however, the food bubble was bound to burst; by the end of 2008, in fact, wheat prices on the Minneapolis exchange tumbled precipitously from their ethereal height. But the fall brought little relief to North African consumers, as grocers continued to charge lofty prices to compensate for their unanticipated losses. And as the American economy stabilized and began to “recover” under the auspices of the Obama administration, speculation propelled the price of wheat upward again, like as much rocket fuel.

Fig. VIII

Global wheat prices from 1993-2013. Both volatility and prices increased after the year 2000, reflecting the speculation of investors. Meanwhile, roughly a billion more people were subjected to food insecurity when wheat prices reached a record high in April 2008. Source: Index Mundi

Particularly if they’ve become accustomed to life in a totalitarian state, people do not typically take to the streets en masse. But when lives are on the line, as the lives of tens of millions of Arabs were, rebellion is ineluctable. Beginning on January 25, 2011, Egyptians—emboldened by the actions of Bouazizi and their neighbours to the north—hastened to Tahrir Square to demand the resignation of Mubarak.

7.3 Building momentum

Not long afterward, protests spread throughout the Arab world, while anti-austerity marches and demonstrations blossomed in Europe. Greek protesters clashed with riot police in Syntagma Square. In Madrid and throughout Spain, Los Indignados rejected the brutality of the conditions imposed on their country in order to secure a loan from the European Central Bank. After the collapse of real estate prices (again, inflated by reckless banks and their investors) had already left millions of Spaniards destitute, the nation’s coffers empty, and valued social services in the crosshairs of vulture capitalists, many of them, like their Egyptian and Tunisian brethren, were quite literally fighting for their lives.

Kalle Lasn of Adbusters, who admits that few things excite him quite like the prospect of a peaceful revolution, was in Vancouver, watching on television as a torrent of indignation flooded scores of countries. The ideal moment had arisen, he and his Adbusters editorial staff reasoned, to issue a call to action, a manifesto for citizens of the world to challenge the powerful in their lofty perch, to storm the walls of their modern Versailles at the mouth of the Hudson.

“We knew that the moment was ripe for something big to happen,” Lasn explained. “And I think that we were quite smart, and lucky I guess, to some degree, in zeroing in on something that’s quite provocative. We basically said ‘Ok, there was regime change in all these other places…and now, let’s go for regime change in America. Let’s occupy the iconic heart of global capitalism, which is Wall Street, and just take it over. Occupy the damn place!’”