“Fuel” – where does it come from?

Jul 9th, 2011 by moniquewong

As a concluding post, I thought it’d be fitting to talk a bit about fuel and it’s sources. Many of my previous posts talks about the use of oil and then it stops there. But where does it come from and how is it produced? These are questions worth pondering about.

Of course, it depends on where we are situated in the world, where our oil comes from. I thought though, that I’d dedicate this last post to talking about the petrostate of Canada. Before we start, let’s take a look at this video:

When I first saw this video, I really did get a gush of pride running through my veins. This is what we’re about, what Canadians are! But let’s juxtapose this to pictures like this:

Unfortunately, this is what Canada is also. A petrostate. And we’re one like no other. In fact, it’s wrong to call us oil-rich, cause we’re not. We’re tar-rich. If oil could be called “clean”, than we’ve moved beyond clean oil, we’ve moved onto the dirty bitumen that Stephen Harper likes to call oil. This is what Manning means when he notes that in the 1940s, every barrel of oil invested returned 100 barrels, nowadays, around 10 barrels. When bitumen is extracted (extraction meaning playing tetris with tons upon tons of earth where only half is bituminous sand), it needs to be heated and heavily chemically processed before it can be sold. Not only that, to pass this molass-like consistency product through pipelines, it is most often diluted with more oil to make it run. Throughout this process, earth is shifted numerous times over, forests are clear-cut to get to the earth and the wildlife in the surrounding area disappears.

Nikiforuk in his book “Tar Sands: Dirty Oil and the Future of a Continent” uses a couple of ways to describe this process:

– “burning a Picasso for heat”

– “the resource has no value, other than the value we create”

– bottom-of-the-barrel resource, a signal that business as usual in the oil patch has ended

and finally: “an upgraded version of the smelly adhesive used by Babylonians to cement the Tower of Babel”

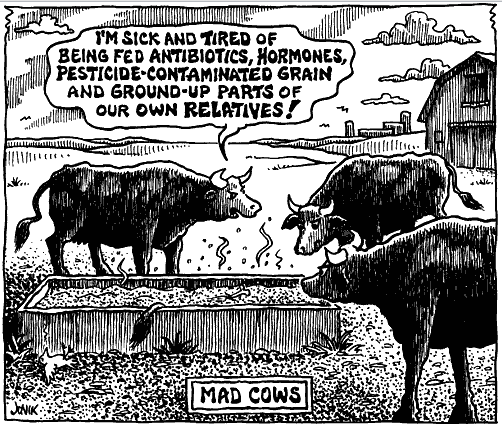

And based on this blog, this is where our food comes from.

Source:

Andrew Nikiforuk, Tar Sands: Dirty Oil and the Future of a Continent (2010), 6 – 37

Richard Manning, “The Oil We Eat: Following the Food Chain Back to Iraq,” Harper’sMagazine, February 2004: 37-45.