I hate club basketball. I have hated club basketball. In all likelihood I will continue hating club basketball. Here’s why:

Exhibit A:

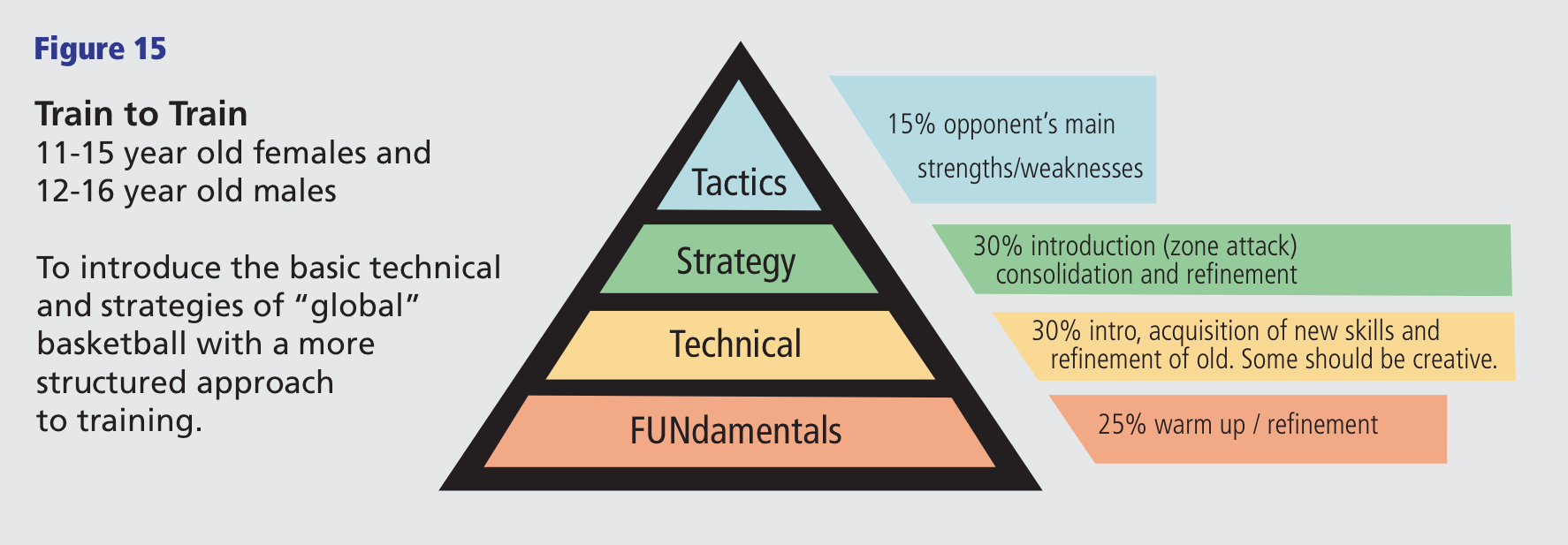

The under fifteen (U15) age group is where club basketball takes over as the primary source of athlete development. The above image outlines our national sport body’s suggested breakdown of coach contact time with athletes. Not only is this not followed en masse, most coaches involved at this level don’t know it exists.

Exhibit B:

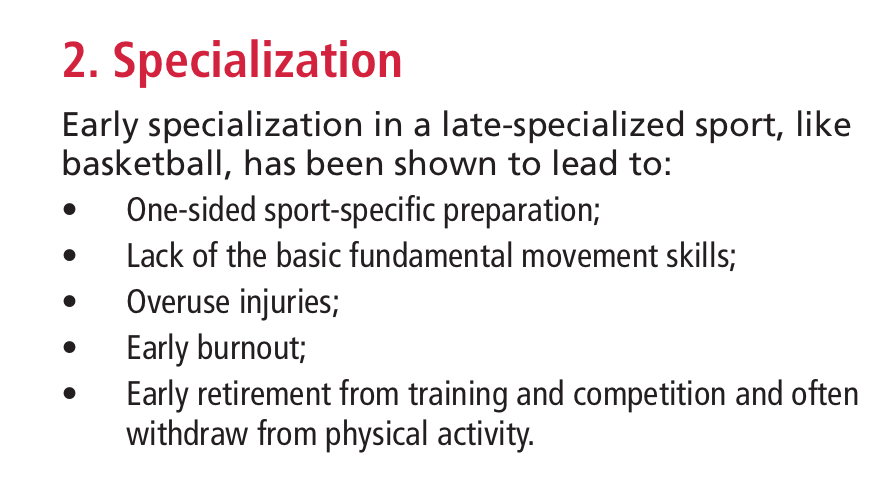

I have twelve athletes on my U15 club basketball team. Of those athletes:

- 100% have poor fundamental movement skills in my opinion

- 100% have not been exposed to fundamental movement training

- 50% are currently struggling with overuse injuries (mostly patellar tendinopathy)

- 16% have talked about quitting basketball all together

Exhibit C:

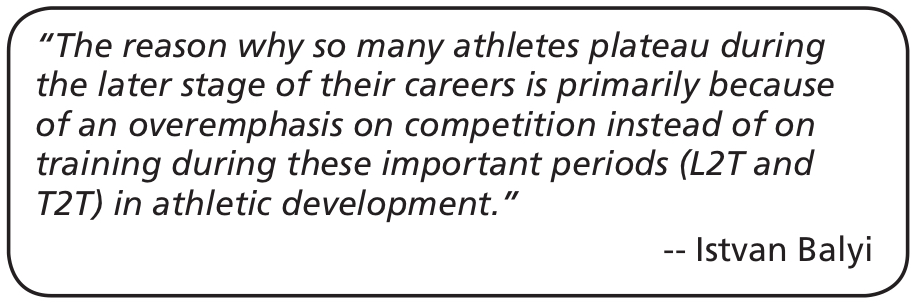

The schedule for my U15 club basketball team (which, for the record, I didn’t create) can be roughly broken down into thirty practices and thirty-five competitions. Based on Canada Basketball’s recommendations for the T2T Part II stage this is where we should be :

– 70% training, 30% competition

This is where we are:

– 46% training, 54% competition.

Not to mention that parents are paying upwards of $3,000.00 for their child to participate in a program that doesn’t follow best practices as it relates to athlete development.

You may be thinking: then why the $^#& are you coaching club basketball?!

Good question…let me explain.

First, I love to coach; I want to be involved. For the past 6 years I have always had a position with our provincial sport organization during the spring and summer. This year though, they didn’t have a position for me. Second, engaging with young players in Edmonton helps me add value to our long-term recruiting plan at MacEwan University. Lastly, all I ever do is complain about the club system as it stands. I figured it was about time to get involved and actually do something about it…

Through my experiences in club basketball I have demonstrated the coaching core competency: Leadership. By identifying systemic shortcomings and working to improve them I have (1) developed and shared a compelling picture of the future for my team, (2) actively listened and proactively communicated with all stakeholders, and (3) have taken responsibility for the development of the athletes on my team. Here’s how:

Different isn’t wrong: Club basketball is fairly homogenous in Alberta. From coaching to style of play, tactics to tournament rules; there is little difference between the 50+ organizations in the province. To make things worse the majority of said programs are pursuing an American Athletic Union (AAU) style of youth development popularized in the United States. At first glance this may not seem like a big deal, after all most NBA players are American, how bad can it be? Well…bad! The AAU is built on hype and money from sneaker companies. They value mixtape highlights and Instagram followers over science based, holistic youth development. As a professor of mine described it, their approach is equivalent to throwing eggs (the athletes) against a wall (the AAU system) to find which ones are hard boiled (tough enough to make it). They get away with undervaluing individual young athletes because of their population size. They have enough eggs to throw and still be successful. Here in Alberta, we simply don’t have enough eggs. Our geographic features call for a more intentional approach. Instead we have become so used to our current approach that anything remotely different is met with skepticism. When I started coaching my club basketball team this spring I was arrogantly expecting my twelve youth athletes to be hanging off my every word because I am an experienced, professional coach. I couldn’t have been more wrong. My approach was, and continues to be, different from what they’ve experienced so far in their short careers. I’ve demonstrated leadership by situating this spring season within the greater context of our athlete’s long term career goals thereby creating a vision of the future that guides our approach as a team. As I’ve explained to them on multiple occasions, I don’t want this spring to be the highlight of their lifelong basketball career. As such we are making decisions based on the collective desire to play post secondary basketball in the future. We have built our strategy to be athlete centric in that we are facilitating game situations that will benefit individual development (i.e. playing strictly player-to-player defence, basing our offence around compounded individual decisions and providing opportunties for every athletes to play meaningful minutes) at the expense of winning more basketball games. My assistant coach and I have managed to convince the majority of our players and their parents of this approach. With two tournaments left, we hope to have everyone on board soon.

Having difficult conversations: At the U15 level, actively listening and proactively communicating includes coach-athlete relationships and, perhaps most importantly, coach-parent relationships. I came into the season knowing that my approach would be different and that a hostile reaction was a possibility. A parent meeting early in the season was a must. I gathered the parents and explained my philosophy. After I emphasized growth mindset and went over the logistics of the season I arrived at the part of the meeting I was dreading…the role of the parent. Whereas our parent meeting occurred a few weeks into the season I was already aware of a few unhealthy situations that would be tricky to navigate. I had decided to be fairly forceful with the parent group and needed to do my research; I needed to be very prepared for a difficult conversation. Thankfully I was able to draw upon True Sport ‘tips for parents to guide the conversation:

The conversation went well and my fears were unfounded. The entire process got me thinking though, how many times do we avoid certain conversations because they are uncomfortable? No matter how difficult a particular conversation may be it is always better than leaving a topic or situation open for individual interpretation, often leading to misunderstanding. More important still is actively listening to your constituents so as to understand their perspective. Through informal interactions with my parent group I have been able to ascertain their motivations for their children. Some align with my philosophy and others oppose it. As I continue to share my vision for their child’s basketball future, hopefully I can convince more of them to see my perspective.

Growth over everything: In my opinion, the most important mandate I have as a youth coach is to ensure the development of my athletes as people, students, and athletes. I’ve made this commitment to my athletes and their parents. One might think such a commitment would be met with appreciation and understanding. In my case that is only partially true. In my current context prioritizing development means sacrificing winning. My athletes, as mentioned above, are chronologically in the T2T stage of development. Intellectually and developmentally though, they remain in the learn to train (L2T) stage having missed several key technical and strategic outcomes. Thus the dilemma: facilitate opportunities for our athletes to work on their weaknesses, in practices and in games, or hide them with tactics and win more. For me the decision was easy and I’ve abided by it to this point. What I wasn’t expecting was the backlash. I half expected the fourteen year olds to been clouded by the industrialization of youth sport. I wasn’t expecting the adults would be as well. Sometimes doing what’s right isn’t popular. Sometimes a leader has to play the role of the bad guy in order to stay on the proper path. My mother, a coach in her own right, has always acted as a mentor to me. In the early 90s she coached a team of synchronized swimmers. Now, almost two decades later, they have tracked her down on social media in an attempt to reconnect. The way she tells it, they weren’t always the sweetest group of girls and she was tough on them. They didn’t appreciate it in the moment but now, as adults, they have perspective and appreciate what my mother did for them. I like to think I will have a similar effect on the athletes I am working with currently.

TL;DR: I hate club basketball but I’m coaching it anyway. My approach is sound and science based but it’s different so no one likes it. I am demonstrating my leadership by articulating a vision of the future for my athletes and facilitating buy in, actively listening and proactively communicating with my constitutents by engaging in difficult conversations, and executing my responsibility to develop my athletes holistically as people, students, and players.

JP

The joys of club basketball. Club basketball has unique challenges as it is the first time sport is a business in many of these athlete’s (and parent’s) lives. The battle between convincing them that a less glamorous route is better for the long term is not easy. Club coordinators are stuck between wanting to attract athletes and do what is best. Unfortunately the attracting athletes part pays the bills and gets far more weight to how a program is structured. With club basketball being relatively new, we need more coaches willing to step in and show the best path for development. Stepping into tough situations and tough conversations is the only way we can bring it to a better place. A saying I heard yesterday that fits for this is “Truth Over Harmony”. The only way we can make the change is if we are willing to confront the truth.

Hi Jackson,

Nice Post, your attitude is refreshing.

As we have discussed over the course of this year, there are many similarities between youth basketball and soccer in Alberta. A heavily focused pay to play model will create a tussle in priorities between player development and revenue generation. Similar to yourself, I have the philosophy that development should be first and as a result our club has lost 14 year old players for reasons such as “we aren’t attending enough US showcase events”.

I feel your pain but keep fighting the good fight!

Jackson, alas high quality sport development continues to struggle. The crux of the problem is the balance between outcome and process. In most sport the outcome is competitive and a desire to compete and win, where as the process is often a means of getting to that end, which, as you have identified, short cuts the development. I continue to be amazed if not saddened by the lack of real change despite the desires of the sport bureaucracy in Canada. LTAD was implemented in 2006 as an agent for change. Many sports, basketball in particular, put LTAD as a pillar of their NCCP. Yet we still struggle to create the change that could have a real impact on development. I was encouraged to hear that Alberta has mandated that all sports need to have minimum NCCP for coaching (this came from a student in my Uvic class). I am not sure how this will be implemented, but perhaps in a small way educating the sport leaders is one way to make change occur. Sadly, our governments do not seem to see the value in imposing minimum standards around sport and coaching.