Since my initial project proposal in the first week of October, the angle from which I want to approach the issue of appropriation of Indigenous cultural heritage in Western fashion, art, literature and music subcultures has been both clarified and broadened. Originally, I modestly envisioned my project to take the form of a rebuttal to certain “hipster” circles, who typically congregate at music festivals (e.g. Burning Man) and appropriate an assortment of different cultures’ traditional attire. My final paper would, and still will, refer to First Nations, Métis and Inuit perspectives to substantiate the arguments that it will present.

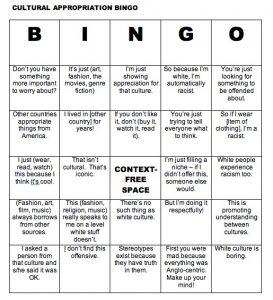

However, while the intention of my project remains (that is, to appeal directly to the violators of culturally appropriative behaviours in an attempt to convince them that these behaviours are immoral and harmful), the target audience to which I am directing my inquiry and the range of resources that it will draw upon have expanded. Upon realising that I have up to ten pages to explore my topic, I decided not only to focus the discussion on the white youth, who shamelessly embrace every opportunity from Halloween to Coachella to “celebrate Indigenous peoples and their creativity” (IPinCH 2015), but also on the companies who manufacture the bootlegged war bonnets and bindis worn by these festival-goers and the “artists” who produce the whitewashed versions of the Indigenous art and music that they obliviously admire.

This decision was influenced by a number of texts I have been reading in my research, which explore the issue from a legal point of view (more on this later), as well as the realisation that the nuances and intricacies of the debate surrounding cultural misappropriation (of Indigenous cultural heritage or otherwise) require a comprehensive analysis of how we got to this point; that is, ethical, social and legal readings of the present and historical contexts of settler-Indigenous relations. With this revised plan, I believe my project will carry greater significance and credibility, in that it will unpack all contributions to the problem at hand and hopefully encourage passive observers to think more about the big picture.

Marx’s idea of commodity fetishism serves as an apt introduction to the discussion and a form of justification for the discordance between Indigenous and Western capitalist opinions on the “sharing” of cultural elements in the 21st century. A concept first introduced in Capital: Critique of Political Economy (Marx et al. 1955), commodity fetishism refers the obscuring of an object’s real value by its economic value in the market. In the context of this discussion, an “object” can refer to products of Indigenous cultural heritage (for example, clothing items, musical instruments, artworks and art styles, languages, etc.). Through this process, traditions with rich cultural histories of thousands of years are reduced to profitable commodities who may be exploited by whoever is willing to invest in the costly process of copyrighting. Couple this phenomenon with existing imbalances of power and it becomes plain to see that the free market poses a real threat to the preservation of sacred Indigenous cultures.

In his article Scenes from the Colonial Catwalk: Cultural Appropriation, Intellectual Property Rights, and Fashion, Peter Shand attributes the main causes of misappropriation to early Enlightenment principles:

“It is a dull fact that the initial phase of modern cultural heritage appropriation was underscored by the twinned ages of Enlightenment and Empire, during which all the world was made over to fit the intellectual, economic, and cultural requirements of first Europe, then the United States. All manner of cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples (from design patterns to artifacts to body parts, even the people themselves) were looted, stolen, traded, bought, and exchanged by colonials of every status (from Governors General to itinerant sealers).” (Shand 2002)

Moreover, he asserts that while Anglo-American law treats tangible heritage (e.g. paintings, dress, sculptures) differently from intangible heritage (e.g. languages, songs, customs), Indigenous peoples typically do not make this artificial distinction. By following this line of thought, I want to emphasise the fact that intellectual property laws are inadequate when it comes to protecting cultural heritage, an idea stressed by the IPinCH project based at Simon Fraser University, in British Columbia (IPinCH 2015).

Indigenous conceptions of property simply do not align with that of European and settler nations, which are based off a “Cartesian proprietary scheme” and ratify a certain domination involved in the possession of an object by a subject (Moustakas 1989). Such a relationship does not exist in Indigenous cultures and hence, it is unfair, to say the least, to impose stringent copyright laws and regulations on products of these cultures. In sum, Western notions of property, material form, authorship and originality that pervade intellectual property law do not translate into anything meaningful in most Indigenous cultures, and hence are used to colonise and erase cultural heritage through convoluted legislation.

By exploring legal, ethical and historical considerations, my final paper will aim to, at least, encourage discussion about casual appropriation of Indigenous cultures in pop culture and niche subcultures and hopefully expose some of the reasons why it continues to be such a problem.

Bibliography

- IPinCH (The Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage).Think Before You Appropriate: Things To Know And Questions To Ask In Order To Avoid Misappropriating Indigenous Cultures. 2015. Vancouver: Simon Fraser University. http://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/sites/default/files/resources/teaching_resources/think_before_you_appropriate_jan_2016.pdf.

- Marx, Karl, Friedrich Engels, Samuel Moore. 1955. Capital. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Shand, Peter. 2002. “Scenes From The Colonial Catwalk: Cultural Appropriation, Intellectual Property Rights, And Fashion”. Cultural Analysis 3: 47-88.

- Moustakas, John. 1989. “Group Rights In Cultural Property: Justifying Strict Inalienability”. Cornell Law Review 74 (6): 1179-1227.