After reading the prescribed chapters of her book for class, I became curious about Chelsea Vowel’s background and decided to do some online research into her. I quickly found that in addition to her main occupation of teaching Inuit youth under protection, Chelsea Vowel, 38 year old Métis academic, mother and author of Indigenous Writes, maintains a blog, on which she posts under the name âpihtawikosisân (which literally means “half-son”, and is the name the Cree gave to the Métis). Her page includes links to many valuable resources related to Indigenous issues in North America (including articles, legal documents and documentaries), language-related materials and intiatives that revolt against the ongoing colonial project in Canada. While she only posts sporadically, her entries discuss incredibly complex topics in Indigenous studies in a conversational tone, making concepts that many white people may struggle to empathize with quite intelligible.

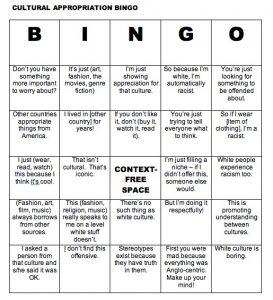

One such topic is the wearing of headdresses by “non-Natives”. This is one of the main manifestations of cultural appropriation in white cultures that I wish I focus on in my Big Idea project and since, like all of her other blog entries, the page links to several other webpages containing Indigenous perspectives and literature on this debate, I figured it could serve as a springboard for deeper investigation on the matter. Before delving into the broader idea of un-/restricted symbols of different cultures, she urges the reader to read through the statements on a “bingo card” (shown below).

Vowel’s posts commonly feature similar prefaces as this, effectively anticipating possible reactionary counterarguments or doubts that non-Indigenous readers may have, which would hinder their ability to comprehend the true meaning and intentions behind Vowel’s work. Admittedly, I could identify with a couple of the statements mentioned on the card above at earlier points in my life and therefore, I can appreciate Vowel’s acumen here. Following this, Vowel goes on to discuss the idea of “Restricted Symbols”, by first referring to several examples related to white North America – for example, military medals, Bachelor degrees and other prestigious awards. Here, it is clear that she is tailoring her language and analytical approach to a white audience. This makes sense, as they are the ones who typically perpetrate culturally appropriative practices, however, while doing so is very productive in its own right, it is no Indigenous person’s responsibility to cater discourse surrounding these ideas to settlers. For this reason, I deeply admire Vowel’s approach of simplifying an idea especially for the intended audience, despite the deeply emotional response she may have to it as a result of her heritage.

She continues this direct tone through to the conclusion, where she seems to comfort the reader in saying that “It’s okay to make mistakes” and insinuating that many white people are simply ignorant to what constitutes appropriation and why it is problematic. However, she states that the best response to being confronted about such behavior is to acknowledge the situation and possibly apologize. I think a suitable addition to this list would be to learn from it. This very idea of having to inform people of how to react to being “called out” appeals to a trickier, overarching problem of “white fragility” and “white guilt.” In pursuing my research topic, I anticipate that these notions will prove to be pertinent in unpacking the reasons why cultural appropriation of Indigenous cultures continues to be a contentious topic that many people still struggle to acknowledge and understand the connotations of.