Given its short documented history and lack of recognition in international law, sexual violence in conflict environments remains a contentious field of study. Both the PRIO and USIP policy briefs uphold that in addition to this perceived political insignificance, methodological shortcomings and equivocal definitions have rendered most conclusions regarding the patterns of wartime sexual violence invalid. In acknowledging the complexity of the issue and the discordance between how relevant terms are defined across studies, both reports accordingly address the definitional considerations in their first pages.

The PRIO policy brief, Sexual Violence in Armed Conflicts, outlines how the legal definition of rape in conflict has evolved since its inception following the ICTR (International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda) and ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in 1993, showing that formal meanings assigned to these novel terms are merely tentative, prone to policy changes and volatile international political relationships. While this isn’t necessarily negative, the USIP report, Wartime Sexual Violence: Misconceptions, Implications and Ways Forward, attributes the slow accumulation of relevant knowledge to these ambiguities, and explicitly states that it does “not advocate any particular definition” in order to maintain credibility even as these definitions are reformed.

The PRIO brief gives an abridged timeline of sexual violence in armed conflict since 1980 and the UN Security Council Resolutions that were introduced in response. The report arrives at a small set of suggestions for scholars and policymakers, namely to direct their efforts toward the plight and status of war children, the impact on the reproductive health of victims, the stigmatisation of victims and commonly held misconceptions about the perpetrators, victims and motivations of wartime sexual violence.

Much of the paper examines the history of this violence, whereas the USIP report addresses ten common misconceptions surrounding the issue, effectively summarising a comprehensive list of existing literature and statistics, all of which was published post-1980. In doing so, it unpacks and interrogates simplified hypotheses that attempt to infer causal relationships between contextual variables, demographics and prevalence of wartime sexual violence, such as those adapted from Seiferf (referred to in PRIO report):

- Sexual violence is an integral part of warfare

- Sexual violence is a weapon of terror and revenge, used to inflict humiliation upon male opponents and to reaffirm own masculinity

- Sexual violence can be understood as a way of destroying an opponent’s culture

- Sexual violence can be seen as an outcome of misogyny

For example, in the conclusion, the first hypothesis in the list above is challenged as the authors compare the passive victims of both rape and gun violence during wartime – the former were intentionally violated, whereas in most cases where noncombatants are killed by crossfire it is accidental.

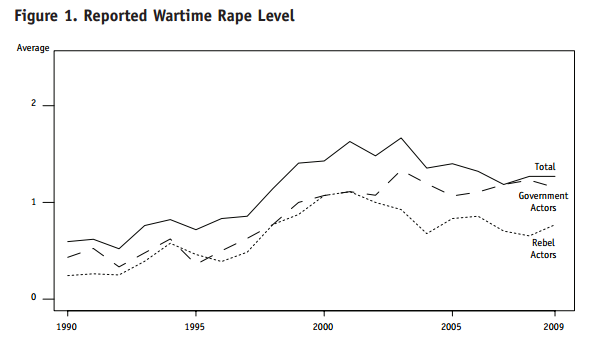

Furthermore, the authors challenge misconceptions related to the ubiquity of sexual violence in war, the prevalence of the problem in African countries and ethnic wars, the gender of victims and perpetrators (as well as whether they belong to rebel groups, state militaries or are even combatants at all), the nature of the violence (whether it is strategic or opportunistic) and claims about trends in wartime sexual violence. These misconceptions, and the recognition of flaws in our current knowledge of the phenomena as well as commonly accepted false correlations (for example, between decreasing overall level of lethal violence and decreasing level of wartime rape) form the basis of the policy recommendations made at the end of the report.

Overall, the analyses are thorough and give clear direction to future research and policy. However, one drawback of the policy briefs is that they fail to adequately explain the reasons for and effects of these misconceptions. For example, upon reading the “Misconception: An African Problem” section of the USIP report, I thought about how media biases play a major role in influencing these misconceptions. In particular, how perpetuation of nationalist principles and white saviour narratives by Western mainstream media outlets effectively absolves colonial military forces from responsibility for instances of wartime rape, and hence from prosecution. In turn, such sexual violence is associated with the “other,” or that which is foreign, which breeds fear of and contempt for immigrants, ethnic minorities and people of colour living in the U.S. and other white imperialist nations.

______________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

- Chun, Suk and Inger Skjelsbæk. 2010. Sexual Violence In Armed Conflicts. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO).

- Cohen, Dara Kay, Amelia Hoover Green, and Elisabeth Jean Wood. 2013. Wartime Sexual Violence: Misconceptions, Implications, And Ways Forward. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace (USIP).