As told by “Shining Path,” during 1980 to 1999 in Peru, a communist group called the Shining Path terrorized communities. Their aim was to institute communism first in Peru, then to expand to the entire world. They believed that death for their movement was the ultimate sacrifice, and they reinforced this ideal through “blood quotas” which often resulted in large-scale executions. The rural village of Ayacucho was one of their primary footholds, as it was made up of vulnerable indigenous peoples who often felt alienated from Peruvian culture. As a result of this affiliation, the Peruvian military would go on to decimate Peru’s indigenous population (2015).

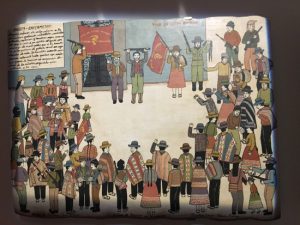

Piraq Causa, meaning “who’s to blame”, is a feature in the “Arts of Resistance” exhibit at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology. This series of 5 paintings depicts the Shining Path conflicts of Peru, events which resulted in over 69,000 people, largely made up of innocent indigenous villagers, being killed (“Shining Path,” 2015). It is the story of the villagers of Ayacucho that these paintings illustrate. The traditional style that these works are painted in, as articulated by Gonzalez, are called tablas pintadas, and were originally used to “depict family genealogy” (2018). However, they are being used in the context of these paintings to illustrate the collective history of the culture during this time. They are intended to denounce the horrors committed against them, as well as to rebel against the erasure of their culture by the Peruvian government.

A Piraq Causa painting (photo credit: Lee (2018))

The initial goal of these paintings was to condemn the atrocities committed against the Ayacuchano people. As one of the poorest indigenous communities in Peru, Ayacucho was easily infiltrated by the Shining Path insurgents (“Shining Path,” 2015). As Gonzales recognizes, though public perception was that the villagers supported the movement, the paintings tell a different story. Indeed, they name the insurgents onqoy, a plague or sickness on the community (2018). This is significant as it runs contrary to the official position of Peru, which unjustly labeled the paintings as pro-terrorist (Osorio Sunnucks, 2018). Perhaps the most horrific scene painted depicts military helicopters gunning down everyone in sight, guerillas and civilians alike. Osorio Sunnucks explains how focused the government was on eradicating the Shining Path, so focused that they completely disregarded the innocents who were unable to defend themselves from the attack (2018). As illustrated through the callous indifference the government had towards indigenous life, it’s clear that they did not care if the Ayacuchan culture survived.

The Ayacuchanos, however, do care. The use of the tablas pintadas method is the artist’s way of showing that no matter what, their culture will persevere. More than just the killing of the Ayacuchano people, the conflicts – which disproportionately affected indigenous peoples (“Shining Path,” 2015) – were a form of cultural genocide. A specific example from the paintings shows the Peruvian military destroying the Ayacucho community center as a way of targeting the Shining Path. However, the insurgents had no vested interest in the community (Osorio Sunnucks, 2018), and therefore the only people who were affected were the villagers whose cultural history had just been wiped out. After the conflicts, the remaining Ayacuchanos scattered themselves around Peru, leading to a loss of their customs (Arts of Resistance: Politics and the Past in Latin America, 2018). Through the use of traditional techniques, the artists are preserving a part of their culture and rebelling against a government that has marginalized and attacked them. Even as recently as 2017, the Lima Museum was criticized for showing these pieces, as they are seen as pro-terrorist (Gonzales, 2018; see also Osorio Sunnucks, 2018). As Schaffer and Smith (2004) observe, life narratives are “often banned in their country of origin,” (p. 16) as they typically reflect negatively on the country itself.

The Piraq Causa paintings displayed in UBC’s Museum of Anthropology depict the atrocities committed against indigenous groups during the Shining Path conflicts. They challenge the official rhetoric of the Peruvian government which paints the indigenous people as insurgents, supporters of the cause who had to be stopped. Not only do these paintings bear witness to the extreme actions taken by the government and the Shining Path, they are also a way for the Ayacuchanos to preserve their culture through the use of traditional techniques.

Works Cited

Arts of Resistance: Politics and the Past in Latin America. 17 May-30 Sept. 2018, Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver.

Gonzales, Olga. “Art Under Attack in Peru.” NACLA, 29 Aug. 2018, www.nacla.org/news/2018/08/29/art-under-attack-peru. Accessed 29 Sept. 2018.

Lee, Tara. A Photograph of a Piraq Causa Art Piece. Inside Vancouver, 17 May 2018, www.insidevancouver.ca/2018/05/17/vancouvers-moa-launches-new-exhibition-on-latin-american-artistic-resistance/. Accessed 30 Sept. 2018.

Osorio Sunnucks, Laura. “#4 Resistance in Chile.” YouTube, uploaded by Kennedy Wong, 17 Sept. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zCEL155PniA&t=0s&list=PL5a14FT4xSaqZAQXgImGwHBBA-aI6QMHI&index=5. Accessed 29 Sept. 2018.

Schaffer, Kay, and Sidonie Smith. “Conjunctions: Life Narratives in the Field of Human Rights.” Biography, vol. 27, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1-24.

“Shining Path.” Peru Reports, 20 Mar. 2015, www.perureports.com/shining-path/. Accessed 29 Sept. 2018.