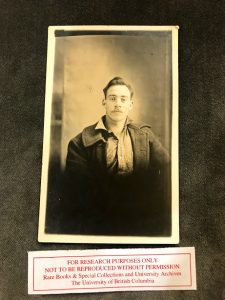

“Jack Stickney”

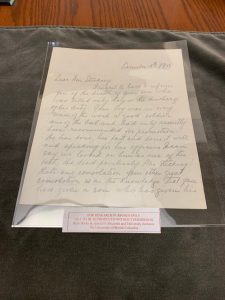

Jack Stickney was a Canadian soldier who fought and died in WWI on December 18, 1915 (Locke). Many of his documents are preserved in UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections and provide insight into his life and death. One of these documents, a letter sent to Mrs. Stickney by Lieut. William Beecher Locke, informs her of her son’s passing and offers condolences. Using Victoria Stewart’s insights into WWI memoirs, I will demonstrate that Locke’s letter is representative of the experience of writing about war because it follows certain conventions, but also that its more personal nature offers insight into the war that other sources may not be able to provide.

Stewart notes that when writing about war, people struggle to “glorify those who died in war without glorifying war itself” (Winter quoted in Stewart 38). This theme is present in Locke’s letter, as he writes “your boy was in every sense of the word a ‘good’ soldier,” and further that “we looked on him as one of the best” (1), thus glorifying Jack Stickney. Locke also mentions that Stickney died “in the defence of the innocent” (2), and though it seems to justify the war, it also fulfills another of Stewart’s conventions. She asserts that “patriotism can give a purpose to, if not comfort for, the loss” (43), and because this apparent glorification of the war is very minimal in the letter, it is more likely a commendation of Stickney’s patriotism. Thus, by fulfilling what Stewart outlines as the qualities of war writings, it can be said that it is representative of the genre and the experience of writing about war.

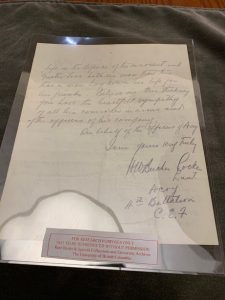

There are also some aspects that make Locke’s letter less conventional. It seems to demonstrate a personal connection to Stickney, evident in the praises of his character, the claim that he “lay down his life for his friends” (Locke 2), and the fact that Locke took the time to hand-write it. Popular sources often depict a contrasting image, with loved ones being informed of the deaths of soldiers through telegrams (“Death Notification”). The efficient and impersonal nature of telegrams as a way to inform loved ones of a death elicits the image of the ‘war machine’ uninterested in individual lives. And while telegrams were most likely the main method used (indeed, the Stickney fonds includes a telegram to Mrs. Stickney apprising her of Jack’s death), the handwritten, personal letter from Locke invites a more nuanced take. By recognizing that there were more than just the quick, insincere telegrams sent by a bureaucratic system that seems to devalue those who fight for it, but also expressions of “heartfelt sympathy” (Locke 2) we can re-evaluate the notion of the ‘war machine.’ This is validated by the fact that the letter is representative of the genre of war writing (according to Stewart’s view).

Overall, Locke’s letter to Mrs. Stickney is representative of the genre of war writings, and by extension the experience of writing about war, as it conforms to Stewart’s notion of “glorify[ing] those who died in war without glorifying war itself” (38) and of consolation through patriotism. Due to its handwritten, personal nature, it can also deepen our understanding of remembrance, the unique intimacy between soldiers, and can question the notion of the ‘war machine.’

Works Cited

“Death Notification.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Nov. 2018, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_notification.

“Home.” Rare Books and Special Collections, UBC, rbsc.library.ubc.ca/.

“Jack Stickney.” Photographic postcard. n.d. Box 1 File 15. Jack Stickney fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.

Locke, William Beecher. Letter from William Beecher Locke to Mrs. C. H. Stickney. 18 Dec. 1915. Box 1 File 18. Jack Stickney fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.

Stewart, Victoria. “‘War Memoirs of the Dead’: Writing and Remembrance in the First World War.” Literature & History, vol. 14, no. 2, Nov. 2005, pp. 37–52, doi:10.7227/LH.14.2.3.