Indigenous Futurism is a platform by which Indigenous peoples are able to combat dominant narratives that feed into the colonial project and the notion that Indigenous people are “in the past”. To define Indigenous Futurism within the context of this paper, I will draw on outside sources such as Alicia Inez Guzman. My definition of Indigenous Futurism is best illustrated when Guzman states that those who create Indigenous Futurism, “embrace technology in all it’s instantiations, from the galactic machinations presented in the compilation to game design, Indigenous speculative fiction writing, artistic production, and the potential for space travel, whether imaginative or cosmological…the understanding that technology is essential to contemporary Indigenous constructions of selfhood contrasts longstanding notions of Native peoples as artifacts of a bygone past” (Guzman, 2015). Therefore, Skawennati demonstrates Indigenous Futurism through new media that hosts an imaginary of future Indigenous peoples. This imaginary combats colonializing discourses of Indigenous people by demonstrating the agency of Indigenous people to decide their own future, as well as highlighting the resilience and survivance demonstrated by characters in TimeTraveller.

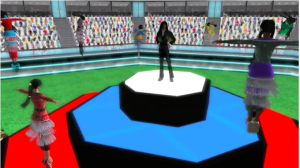

Floating Jingle Dancers

One of the starkest examples of Indigenous Futurism in TimeTraveller is that InterGalactic PowWow in 2112. Karahkwenhawai dances among the rows of Jingle Dancers as the commentator discusses past tales of how the PowWow was historically banned because of fear that Indigenous people would “plan.” The commentator also notes how Indigenous people met in private as a method of resistance, until the PowWow became an internationally (and intergalactically) recognized and televised event. The tale of how the PowWow was previously banned is met with boos and anger from the audience, a clear demonstration of Indigenous resistance. Additionally, the floating jingle dancers point out how the intergalactic Powwow is not just a resurgence of publically held Indigenous traditions, but building on traditions to add a new dimension to Indigenous celebration. The regalia fashion advertisement on the big screen is important because it highlights how in our current world, Western displays of fashion are the unmarked “norm” in society. Skawennati’s world imagines regalia as being the norm in international fashion shows. The famous “Dead Mohawks” band that plays on the big screen during the PowWow is another assertion of Indigenous survivance in a futuristic context. It is also worthwhile to note that the PowWow takes place at the Winnipeg Olympic stadium, a nod towards how in the future Indigenous people will reclaim spaces historically European spaces (as the Olympics were born from Greece) where Indigenous peoples have been marginalized.

In addition to futuristic settings, scenes from the past are also reimagined through an Indigenous lens. Although these scenes exist in the past, they are still an example of Indigenous Futurism because of the insertion of Indigenous technological perspectives into the scene. In Episode 3, Hunter is portrayed in the opening scene as the Mohawk warrior from the famous photograph of the standoff with a soldier during the Oka Crisis. The original photograph and the media that followed frames the Mohawk warrior as a danger to the white soldier, however in TimeTraveller we hear the soldier say the word “motherfucker” to Hunter. This is a side of the story that was not depicted in the framing of the Oka Crisis by dominant media at the time. Although this is a photograph of a scene from 26 years ago, Skawennati is able to critique and examine it in a futuristic context.

TimeTraveller

Original Photograph

Adding to the layers of Indigenous Futurism in TimeTraveller, there are many ways by which Skawennati engages in screen sovereignty by creating an Aboriginally-determined cyberspace. As Lewis and Skawennati stated, “The World Wide Web has offered us the possibility to shape our own representations and make them known” (2005). Hunter and Karahkwenhawai are avatars that self-determine their position in time and the identity they choose to take on when entering a new time period, such as when Karahkwenhawai chose to participate as a jingle dancer or Hunter chose to sacrifice himself at Aztec to he could have a life with Karahkwenhawai. Additionally, Shakwennati draws attention to the different confederacies for different nations that were created alongside countries such as Canada or the United States of America in the future. This is an another example of Aboriginal screen sovereignty that shows Indigenous nations having sovereign rights.

Although Hunter and Karahkwenhawai are able to self-determine their identity, they cannot change the events of the past. However, they are very much the heroes of the story. They support the people of the scenes they visit indirectly and their influence is felt greatly. At Alcatraz, they supported the actions of Richard Oaks in reclaiming the land, and Karahkwenhawai supported Kateri Tekakwitha in her final days. The justice-seeking and advocacy that Hunter and Karahkwenhawai reminded me greatly of the vigilante protagonist from A Red Girl’s Reasoning by Elle-Maja Tailfeathers.

On the next episode of TimeTraveller:

Hunter and Karahkwenhawai travel back in time to Virginia in the 1600’s. They meet Pocahontas and learn about her home, her interests and her personality. They follow her on her journey to England and witness the events that led to her death. Since Hunter and Karahkwenhawai cannot change the past, Karahkwenhawai would write a book about what actually happened to Pocahontas. She could also choose to create an art exhibit dedicated to her, either in 21st-century style art by painting a portrait of what she really looked like, an online gallery, or a futuristic virtual reality headset where one could visit her home of with the Powhatan nation. The choice of music would also be very intentional as it was in TimeTraveller, with songs that fit the mood of the particular episode but also range from techno music to drumming and singing, with some songs being a mash-up of both. Hunter and Karahkwenhawai would travel all around the world and talk about Pocahontas’s life (and they would travel from country to country on a Mohawk passport successfully). They would talk about her spirit, but they would also acknowledge how Pocahontas was previously a classic Disney film the problematic Indigenous representation in the film, and also how many people didn’t understand how young she was at the time of her death. They would tell people that her real name was Matoaka. They would talk about how many people have dishonoured Pocahontas’s memory in the past but they would also discuss how we can honour her in the future. Due to Hunter and Karahkwenhawai’s advocacy and truth telling, people would build a memorial for her in the city of Montreal and Virginia, and people who visit her grave in London would leave flowers at her grave regularly.

Pocahontas’ Grave

To conclude, Skawennati’s vision is not what the world would look like in the future if settlers had never made contact- it is instead an excellent example of Indigenous Futurism from where we are now and resistance to the colonial project. It is an example of what the world could look like in the future.

References:

Lewis, Jason and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito “Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace” Cultural Survival, 29.2, 2005. Accessed Nov. 29, 2016

Guzman, Alice Inez. 2015. Indigenous Futurisms. InVisibleCulture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture. Retrieved Nov. 30, 2016. URL: https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/indigenous-futurisms/