Introduction

Plants can lend therapeutic benefits and foster gardens of care, benefiting mental and physical health. Both the act of plant management including watering, pruning, and planting as well as the physical properties of plants can benefit human health through interaction. There are many physiological studies of the characteristics of restorative landscapes such as landscapes with a higher degree of mental involvement lending greater mental engagement (e.g gardening)¹ and in ‘Image of a City’, Kevin Lynch proposed that humans are attracted to pattern-seeking in landscapes². Patrick Mooney posits four characteristics of a restorative landscape including (1) a degree of fascination, (2) the experience of ‘being away’ from somewhere either geographically or physically, (3) the extent of content, structure, and size, and (4) compatibility with no effort required to enjoy³.

History

Content adapted from Therapeutic Gardens: Design for Healing Spaces⁴.

The therapeutic qualities of plants have long been recognized through garden design, drawing back to the first therapeutic gardens of the Persian chahar bagh designs such as the Bagh-e-Fin, the oldest garden in Iran. Designed in 1590, Bagh-E-Fin in Kashan, Iran utilizes geometric patterns diverse vegetation of shade and fruit providing trees, shrubs, and flowers, and a sentiment of control which influenced gardens around the world from Spain to India⁵.

Bagh-E-Fin in Kashan, Iran recognized the value of planting trees for shading and cooling through linear accompanyment to channeled water.

In Japan, the role of moss in the garden accompanied religious contemplation as observed in the 1300- year old Saihoji Rinzai Zen (Moss) Temple in Kyoto⁶. Moss has long been recognized for health benefits of healing wounds and reducing wound infections⁷.

The Saihoji Rinzai Zen (Moss) Temple in Kyoto, Japan.

The Italians recognized the medicinal value of grouping and documenting plants with mental and physical health benefits in medicinal gardens for research, such as the oldest medicinal garden and University Botanical Garden from 1545, Orto Botanico, in Padua, Italy⁸.

Water lily ponds at the botanic gardens of Orto Botanico in Padua, Italy, one of the oldest medicinal gardens in the world.

In North America, Indigenous peoples have long-recognized the benefits of medicinal plants, including the Coast Salish people’s practices of food and medicine in the design and management of plant resources as observed locally in British Columbia through springbank clover patches of the Nuu-cha-nulth peoples to Wapato patches in Pitt Meadows⁹. The Katzie First Nation managed the health of wetland environments for wapato as early as 1,800 BC and in 2016, construction in Pitt Meadows, British Columbia resulted in the historic emergence of these preserved food gardens.

Wapato - Sagittaria latifolia (or arrowleaf, Indian potato, swamp potato and duck-potato) is a member of the water plaintain family, found in semi-aquatic marsh habitat and known as an ethnographically important food source through it's nutricuous tubers¹⁰.

Therapeutic plants have also been ailments during wartimes where during WWII, victory allotments, the rise of public gardening, and gardens in Japanese internment camps provided social and emotional relief. The expression of ‘Momoyama style gardens’ was an expression for Japanese Americans in harsh, remote conditions who planted trees, community gardens, and ornamental plants in the common space and around the barracks as well as in front of hospitals and orphanages¹¹.

The Manzanar National Historic site, in Inyo County California, USA, featuring a dry koi point in the former gardens planted and managed by Japanese Americans in Japanese Internment Camps.

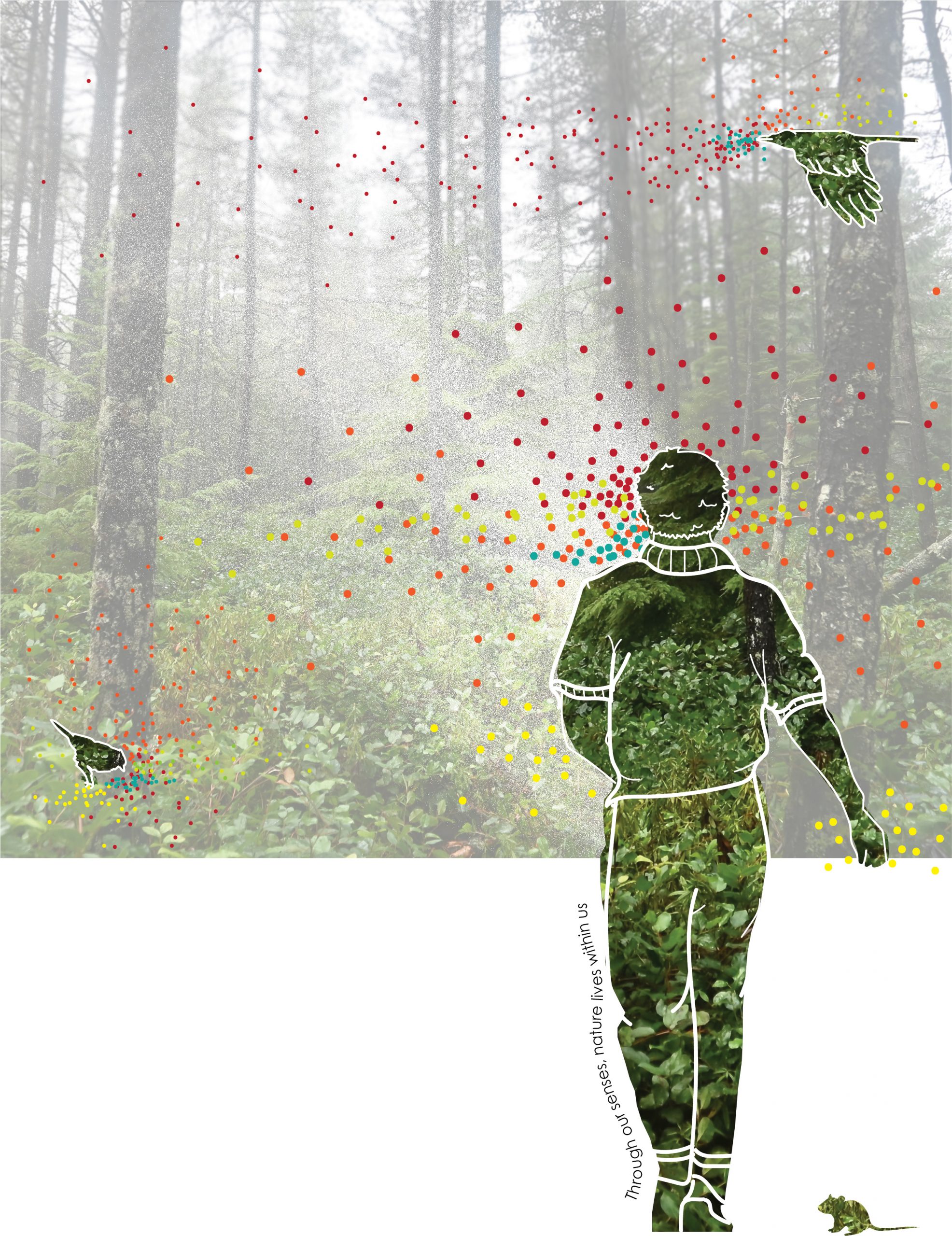

It wasn’t until the 1980s when the English terminology we use today was coined such as the 1980 use of Biophilia by E.O. Wilson. In 2018, the term ‘forest bathing’ or shinrin-yoku was coined by the Japanese Forestry agency to describe the benefits of spending time in the forest and today, doctors prescribe spending time outside to improve mental and physical health ailments¹².

Therapeutic planting selection

The following is a list of general conditions for selecting plants for therapeutic gardens. This list is by no means exhaustive and developed from best practices in the books Therapeutic Gardens: Design for Healing Spaces⁴ and Designing, Planting and Using a Therapeutic Garden¹³. The selection of plants for a therapeutic garden should be in participation with the garden users and will match the site context.

|

Consideration |

Elements |

| Color |

|

| Edibility |

|

| Texture |

|

| Spacing |

|

| Scent |

|

| Sound |

|

| Activity |

|

| Accessibility |

|

| Grading |

|

Case studies

Rainier Beach Urban Farm – Seattle, Washington ¹⁴⁴

Michael Neguse in partnership with Tilth Alliance, provides space for Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees to participate in urban food production in the Rainier Beach Neighbourhood in Seattle Washington. Today, 20,000 pounds of fresh fruit and vegetables are distributed to Rainier Valley residents, facilitating a ‘farm to table’ experience through community engagement. As quoted in a 2017 post by Runta, a Seattle East African news source for Michael’s recognition:

“This program has been life changing for our elder participants. They have decreased their feelings of isolation in their new country, and they have taken on an important provider role in their families and community, all while getting healthy exercise and interacting in English with people of all ages.”

Rainier Beach Urban Farm and Wetlands in Seattle, located on the ancestral lands of the Duwamish Peoples. Photo credit: Tilth Alliance, 2024.

1. Kaplan, Howard. Psychosocial Stress – Trends in Theory and Research. Baylor College of Medicine, 1983.

2. Lynch, Kevin. The Image of a City. The M.I.T. Press, 1960.

3. Mooney, Patrick. Planting Design: Connecting People and Place. Routledge 1st Edition, 2020.

4. Winterbottom, Daniel and Wagenfeld, Amy. Therapeutic Gardens: Design for Healing Spaces. Timber Press, 2015.

5. Fallahi, Esmaeil. Workshop: Ancient Urban Gardens of Persia: Concept, History, and Influence on Other World Gardens. HortTechnology 30(1):1-7, 2019.

6. Saihoji. The Gardens of Origins and Journeys. Saihoji Rin Zai Zen Temple, n.d.

7. Benek, Atakan, Canli, Kerem, and Altuner, Ergin Murat. Traditional Medicinal Uses of Mosses. Anatolian Bryology 8(1), 2022.

8. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Botanical Garden (Orto Botanico), Padua. The List, 1997.

9. Turner, Nancy. Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014.

10. Spurgeon, Terry. WAPATO IN KATZIE TRADITIONAL TERRITORY. Simon Fraser University, 1999.

11. Goto, Seiko. ON THE PURPOSE & ROLE OF JAPANESE GARDENS IN AMERICAN INTERNMENT CAMPS. 2018.

12. Portland Japanese Garden. Shinrin-yoku: The Simple and Intuitive Form of Preventative Care. 2022.

13. Jeffries, Sue. Designing, Planting and Using a Therapeutic Garden. The Crowood Press, 2023.

14. City of Seattle Parks and Recreation. Rainier Beach Urban Farm and Wetlands. n.d.