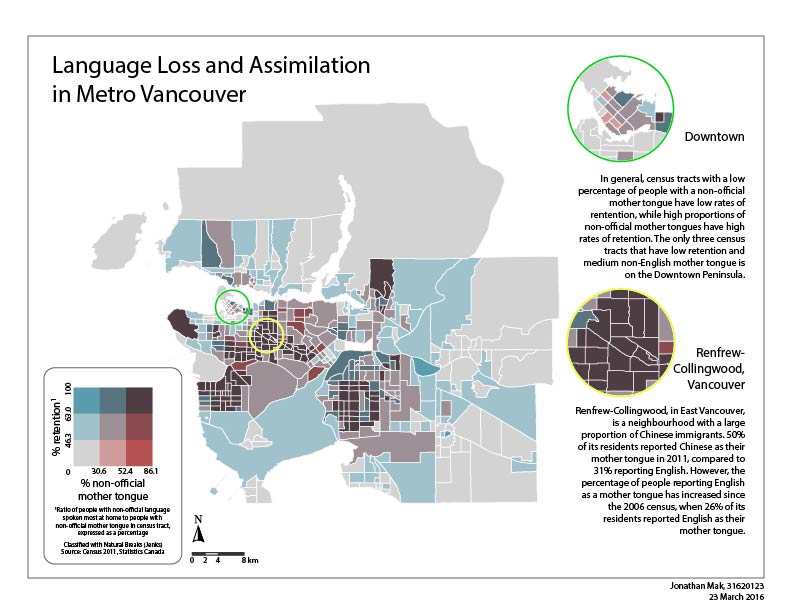

When looking at spatial patterns of people with a non-official mother tongue in the lower mainland, some areas stick out more than others. In areas of south and east Vancouver, Richmond, Burnaby, and Surrey, the proportion of people with a non-official mother tongue exceed 50%. However, there are also clear delineated areas, such as Kitsilano, where the opposite is true, with low numbers of people with non-english mother tongue and low rates of retention.

In locations with a low proportion of non-official mother tongues, the rates of retention are also quite low. This could be because of a larger pressure to assimilate. In the census tracts where there is a lower proportion of people with non-English mother tongue, retention rates seem to decrease.

There are, however, limitations to this analysis. ‘Mother tongue’ is a vague term that does not necessarily have a fixed meaning that is universally agreed upon. It generally refers to someone’s ‘first language’ – but even that is not necessarily a simple question to answer. According to the definition outlined by Statistics Canada, ‘mother tongue’ refers to the first language learned at home in childhood and still understood by the individual at the time of the census. Even with that definition, there can still be ambiguities.

I, for example, learned Cantonese and English concurrently as a child, but used Cantonese more often at home until I started attending school. Soon after, probably around age 7 or so, my Cantonese proficiency was stunted and English became my primary language. I would still consider Cantonese my mother tongue, but some may not. Still, others may consider a certain language their ‘mother tongue’ for cultural or ethnic reasons.

On the other hand, ‘language most spoken at home’ is yet another question that is not as simple as it may seem. In many households, multiple languages may be spoken without a dominating language. The true degree to which language loss is occurring is probably being masked by the fact that the census is most often filled out by the heads of households, who are more likely to be older, foreign born, and primarily speak a non-official language – and may write that that unofficial language is spoken most in their household, despite their children primarily speaking English.