The land on which Strathcona now sits is part of the traditional, unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations, who have inhabited these lands since time immemorial.

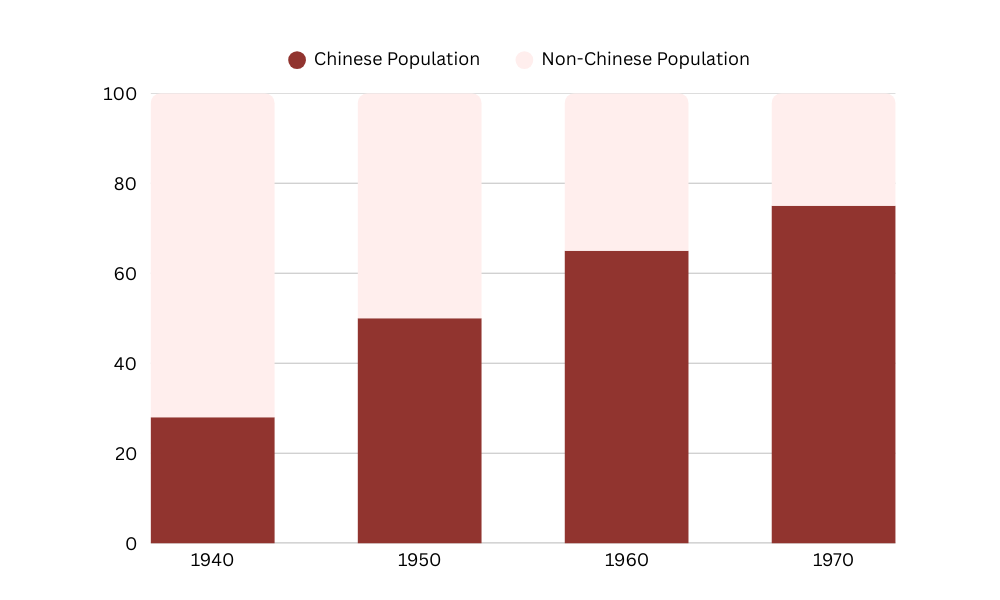

During the exclusion era (1885–1947), when Chinese migrants faced head taxes and severe immigration restrictions, Vancouver’s Chinatown developed as a refuge. Most migrants came from Guangdong, and restrictive policies resulted in a predominantly male population; as well, clan and village associations provided crucial support networks (Madokoro, 2011). After WWII, loosened immigration laws led to an influx of Chinese families, many settling in Strathcona, which offered familiarity and security. Strathcona’s population doubled between 1951 and 1961, with ethnic Chinese residents increasing from a quarter in the late 1950s to three-quarters by the 1970s—thus, the neighbourhood was sometimes called “China Valley” (Ng, 1999).

Chinese Population in Strathcona

In 1957, the City of Vancouver proposed a twenty-year slum clearance scheme (known as the Urban Renewal Project) targeting Strathcona, which city planners identified as an area of blight. Many residents felt the area was being targeted due to its largely ethnic, and seemingly voiceless, Chinese population (Madokoro, 2011).

The Chinese Benevolent Association (CBA) warned of Chinatown’s decline and compared the plan to WWII-era Japanese Canadian displacement. In 1968, the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) formed, using public engagement and political lobbying to halt demolitions. By 1969, the city abandoned the clearance plan, instead funding the Strathcona Rehabilitation Project. In 1967, Vancouver proposed a freeway through Chinatown’s commercial district. SPOTA and the CBA protested, calling it the “death of Vancouver’s Chinatown” (Madokoro, 2011). By 1970, SPOTA leveraged its role in Strathcona’s rehabilitation to block the freeway. Victories in urban renewal and freeway fights bolstered Chinese-Canadian political activism, leading to initiatives like cooperative housing, the Strathcona Community Centre (1972), and the Chinatown Historic Area Planning Committee (1975) (Ng, 1999).

By the late 1980s, tensions emerged between established Chinese-Canadians and newer Hong Kong migrants. In the “monster homes” controversy, affluent investors built large houses in Shaughnessy and Kerrisdale, clashing with white residents over neighbourhood aesthetics. Peter Kwok, a Hong Kong immigrant, remarked, “Chinatown didn’t matter. It was a part of history,” reflecting a divide between new arrivals and long-standing Chinese communities (Madokoro, 2011). Chinatown leaders largely stayed out of the dispute, revealing weakened ties between past and present diasporic experiences.

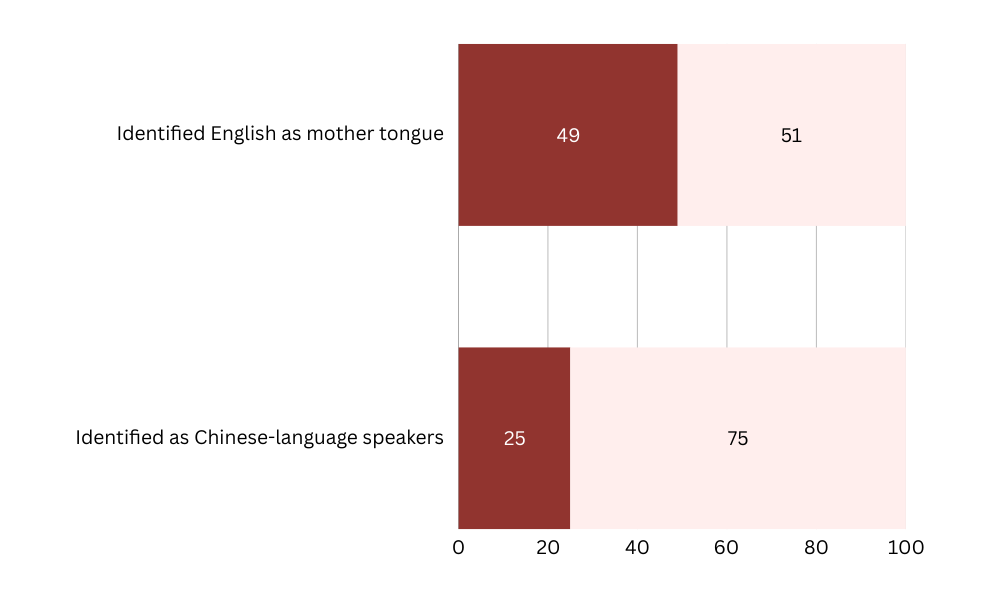

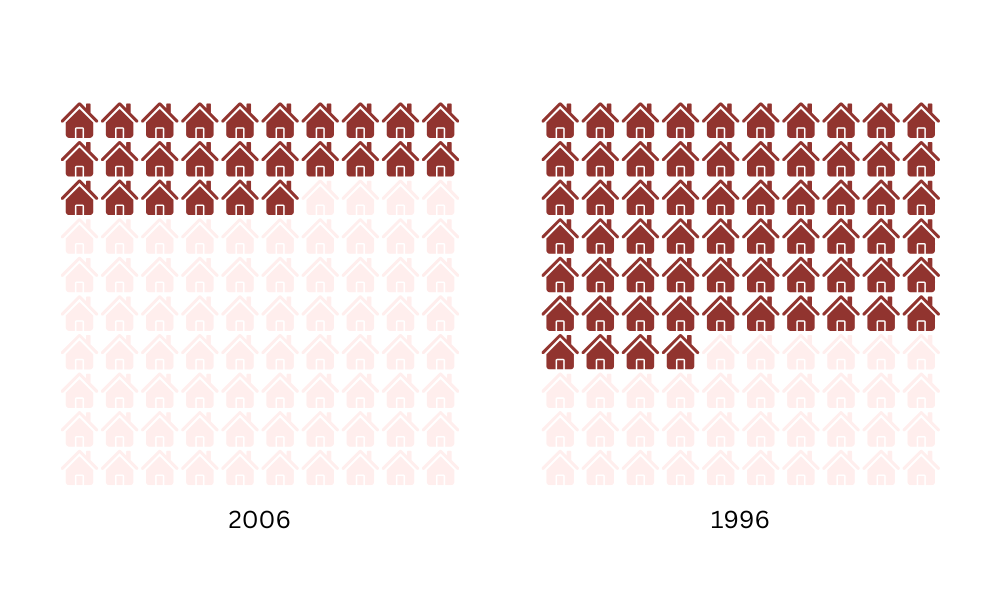

Strathcona’s Changing Population

By the early 21st century, gentrification transformed Strathcona. By 2006, English was more commonly spoken, long-term residents declined, and the 2007 sale of Strathcona’s first million-dollar home symbolized this shift (Kalman & Ward, 2012; Madokoro, 2011). Meanwhile, Chinatown increasingly relied on heritage and tourism, diminishing its role as a cultural hub.

References

Kalman, H., & Ward, R. (2012). Exploring Vancouver: The Architectural Guide. D & M Publishers.

Madokoro, L. (2011). Chinatown and Monster Homes: The Splintered Chinese Diaspora in Vancouver. Urban History Review, 29(2), 17–24.

Ng, W. C. (1999). The Chinese in Vancouver, 1945-80 : The Pursuit of Identity and Power (1st ed.). UBC Press.

1 Kalman, Harold, and Robin Ward. Exploring Vancouver: The Architectural Guide. D & M Publishers, 2012.