Introduction

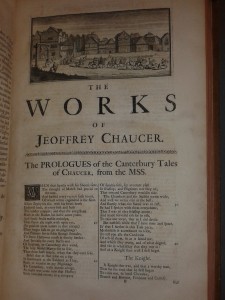

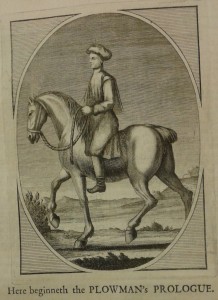

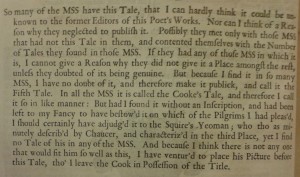

The 1721 John Urry edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s works is a unique assemblage of this popular author’s literary achievements. This massive book includes “three tales…which were never before printed.” However, these tales are not to be found in this edition. The tales as mentioned in the title are “The coke’s tale of Gamelyn; The marchant’s second tale, or The history of Beryn; and The adventure of the pardoner and tapster at the Inn at Canterbury” (https://know.freelibrary.org/Record/873745). Of these, “The Coke’s Tale of Gamelyn” is found in this edition of Chaucer’s works, yet the other two additional tales are not included. Although, there is one additional tale in this edition that is not found elsewhere. While the title does emphasize that these three additional were found in “many valuable manuscripts.” This one additional tale, as described in its own, peculiar introduction, is said to have been found no where else, yet is attributed to Chaucer. That tale is the Plowman’s Tale, which is in no modern editions. The editor claims that “this tale is in none of the manuscripts that [he] [has] seen” (Urry 178). The sole witness to this tales inclusion in The Canterbury Tales is a Master Stowe, who “carefully collected and preserved” this tale in his library (178).

Though this edition of Chaucer’s works is not an ideal study tool, it does allow the modern scholar or reader to view what was valued by those in the 18th century. Urry’s preservation of Chaucer as an important figure in English history, is not extended to his literary work. That is to say, that these liberal changes made to The Canterbury Tales alter the tales and the interactions between the pilgrims, themselves. Without this mediation, were the texts preserved as we are privy to them today, there would be more assurance of Urry’s intent. However, Urry was making these texts accessible to the 18th century reader, which assumes that the 18th century reader is not capable of understanding or accessing Chaucer. This mediation of Chaucer, on Urry’s part, demonstrates that Chaucer is timeless, regardless of any perceived language barriers.