I am so happy I took this survey course which introduced me to European and Latin-American authors writing in the “Romance languages”. Some of the readings were definitely challenging and different, but I believe that the only way one can learn and grow is by forcing oneself to read challenging texts in different genres.

I definitely expect more of myself now, especially living in a world that is increasingly embracing a global monoculture that is dominated by American and western values and lifestyles. My dream is to one day be able to read authors in the original language because so much gets lost in translation. As Dr. Jon mentioned in the final lecture:

“In the global distribution of power and knowledge, more and more it is only English that counts, and even languages such as French or Spanish are relegated to conveying cultural particularity rather than being seen as vehicles for thought. Moreover, that particularity is to be translated into English for it to become intelligible, comparable, quantifiable.”

As an Arab speaker, I could not agree more. No translation of the Holy Quran can capture the beauty of the Arabic in which the Quran was revealed. No translation of Rumi can capture the true essence of the man and many Persian speakers cite the criminality in modern interpretations like those of Coleman Barks, who does not speak Persian nor understands basic principles of Islam. It is truly tragic that Goethe’s utopian idea of “World Literature” in which no single language or nation dominates has only remained an “ideal” or an “aspiration” and nothing more. Not every form of market freedom and growth is good, especially when it comes to “world literature”.

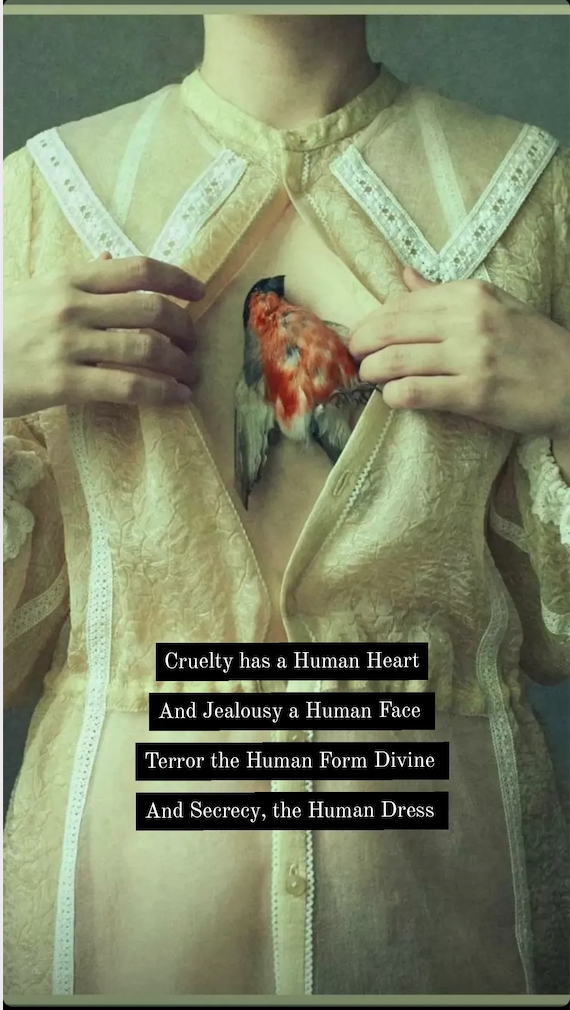

On another note, I have been sharing quotes from different authors we’ve read this term with friends and family and on social media. These past two years have forced many people to grapple with their own mortality after losing loved ones to COVID-19 and the uncertainty the future holds for many so I shared a few quotes from Bombal’s The Shrouded Woman and Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H. because I felt that these works really resonated with me and others.

I truly believe that it is tragic for one to go through four years of university education without having read any works outside of the “Western Canon”, and it is even more tragic that more and more people are graduating without having read much works even within the Western Canon. I am truly thankful that I was able to read works from both the Western and Eastern canons and also thankful to have taken this course which introduced me to the minor works within the Western Canon.

Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Jon for his wonderful lectures and accompanying transcripts as they helped me understand some of the more difficult texts. I would also like to thank Dr. Jon, Patricio and Jennifer for the wonderful class discussions as these were my favorite part of the course (in addition to the readings). I will no longer be a UBC student come end of term, and my only regret is not having taken more Romance Studies courses.