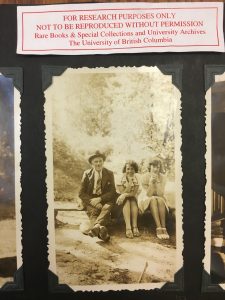

The Library of Rare Books and Special Collections found on the campus of the UBC is almost like a modern day scrapbook from long ago. Uno Langmann’s collection of photographs depicts life in British Columbia in the early years of 1850 through to the 1970’s (UBC Library). One scrapbook titled “Ten Annual Cycling Trips” portrays the lives of two women, Kitty and Clara, over the course of ten summers between 1938-1947. These women used scrapbooking as a way to “preserve memory,” and to help establish a sense of self (Phillips). Phillips further explains how “autobiographical memories” use material objects, such as the pictures and letters in Kitty and Clara’s scrapbook, as crucial pieces in understanding one’s identity and as “souvenirs of the experience to be remembered” (Phillips). By placing themselves in the centre of their own story, Kitty and Clara undergo “continuing interpretation and reinterpretation of [their] experience[s]” (Bruner qtd. in Phillips), and these memories embody their ideas of self.

Today, most people typically use social media as a way to connect with friends online and to keep tabs on each other’s lives. It provides an instant sense of interconnectedness. Phillips notes how scrolling through a social media profile is not unlike flipping through the pages of a scrapbook. Both dispositions provide a personal peek into the creator’s life by “document[ing] friendship and visualiz[ing] their social network” (Phillips). Day refers to both of these platforms as “personal media archives” which allow the creator a choice of maintaining privacy or allowing for public showing. Although social media users have the capability to connect with strangers, most individuals use it to re-establish pre-existing offline relationships. Social media “predecessors [like scrapbooks] appear to have anticipated” and demonstrated real life relationships long before the origination of the online web (Day). Not only are scrapbooks and social media platforms to build memory and identity, they also provide a medium to display and gather “cultural capital” (Bourdieu qtd. in Day). This is defined as “one’s accumulated knowledge about society… obtained through education and credentials, inherited knowledge and the acquisition of high-status goods” (Bourdieu qtd. in Day). Day orchestrates various authors’ arguments who agree on the use of social media and scrapbooking as a way to demonstrate social networks as well as class and wealth, but also as a stage to gather more capital. This is obvious in the use of social media as people use “impression management, identity performance, and/or expression of taste” in order to amass more stature among online friends or followers (Day). Yet, this concept is far less evident in the craft of scrapbooking because it is usually viewed as a personal activity (Day). However, scrapbooks have historically been passed around to share “friendly inscriptions,” or in the familiar terms of social media, comments or captions, perhaps on a Facebook ‘wall’ or underneath a photograph posted online (Day), which then allows for the expression of “cultural capital” (Bourdieu qtd. in Day). In the case of Langmann’s scrapbook “Ten Annual Cycling Trips,” Kitty and Clara are able to demonstrate their affluence through their yearly summer travels and their widespread social circles portrayed in the photos.

Memories bridge the past with the present. The manner in which they are documented has changed, but the importance of remembering is still prevalent in forming one’s identity. Uno Langmann recognized the inherent need to maintain recollections of personal histories. Although scrapbooks and social media provide insight to the times, they cannot be held as historically valid in the sense that they are “messy, fragmentary and highly individualized” (Day). Despite the impermanence of words and images on a screen, social media is a modern day scrapbook.

Works Cited

Good, Katie Day. “From Scrapbook to Facebook: A History of Personal Media Assemblage and Archives.” New Media & Society, vol. 15, no. 4, June 2013, pp. 557–573, doi:10.1177/1461444812458432. Accessed 25 Jan. 2019.

Phillips, Barbara J. “The Scrapbook as an Autobiographical Memory Tool.” Marketing Theory, vol. 16, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 325–346, doi:10.1177/1470593116635878. Accessed 25 Jan. 2019.

UBC Library. “Browse Collections.” Open Collections, The University of British Columbia, https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/langmann. Accessed 27 Jan. 2019.

Wilson, Clara. “[Ten Annual Cycling Trips, 1938-1947].” A. N.p., 1950. Original Format: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. Web. 27 Jan. 2019. <https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/langmann/items/1.0376059>. Uno Langmann Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs.