TV series – perceptual map

The British TV series by Charlie Brooker explores the side effects of the 21st century’s drug: our black mirrors (TV, computer, monitor, smartphones, etc). Each episode brings the viewer to a future not too far from his current life, taking a thread of technology and pushing it to its limits. It is always spot on, not too satirical for us to believe in it and dark enough to make us feel uncomfortable. Maybe the reason why Black Mirror moves us so much is because it flirts with the uncanny valley. The principle of the uncanny valley is that any human representation getting to close to a real human would bring discomfort. It is the same with the series. This representation of our reality is getting so close to what we perceive might happen in the very near future that we feel discomfort. This feeling is put to good use as it makes us think about our current society. For instance some try not to look constantly at their smartphone like drug addicts, to the extent that a word was created: JOMO, joy of missing out, the opposite of FOMO, fear of missing out.

Techno-paranoia is an ever coming back motto that divides the world between tech-lovers and tech-skeptics. A third category should arise, the tech-questioners, citizens who are not satisfied with the status quo of the lazy “so what?” and who wonder what would be the potential consequences. This is why I feel Black Mirror is such a clever show, because it makes us think.

Even though we clearly see the benefit of the progress in technology (not only in terms of communication but also for social and ecological purposes), we cannot shake the feeling that this time the reality is catching up with the fiction. Alright, cars cannot fly yet. But biometry, data collection, wearables, the Internet of things get us very close to SciFi movies (Blade Runner, Metropolis to only name a few). Similarly a century ago or so people were also trying to understand how the future would look like. For instance a German artist in the 30s invented Skype or Facetime:

Superheros and dystopian movies told us to ask ourselves a simple question: what if these technologies were put to bad use or at least to extreme use? And this reminds me of the last Disney, Big Hero 6, where the hero invents a brilliant technology, the microbots…. but in the hands of a hurt father it becomes a weapon. And as a friend of mine pointed out, that is not discussed by any of the protagonists in the movie. Only the villain is punished and there is no shared responsibility. What happen to “with great power comes great responsibility” (quote from Uncle Ben in Spiderman)? Maybe this is an outdated slogan, only good for the Cold War era when the risk of blowing up the planet with a nuclear bomb seemed to be a possible outcome. Should it be “watch out for black mirrors”?

A very insightful link for the French reader: here.

Black Mirror: the explanation of each episode and unofficial trailer.

Internet has disrupted the classic model of the recorded music industry whereby an artist would record a CD, which would generate sells by being promoted on the radio and through live tours. Today people can have access for free, legally or not, to music and the sources of revenues are depleting. This challenge needs to be addressed by music producers who tended to either ignore the facts or stick to the status quo.

The younger generation is the one who largely changed behaviour. Their parents still listen to CDs on their stereo.

The first change was the peer-to-peer downloading platforms that were quickly banned. A paying system that proved more efficient and user friendly took over: iTunes. This proves that a better offer will always be preferred even if the user has to pay for it.

Nonetheless users are shifting from owning the songs to having a simple access to music. That is the streaming model. Acknowledging this trend Apple acquired Dr Dre’s Beats Music, rebranded Beats music, to soon compete with existing streaming platforms. Deezer and Spotify use the freemium model in which 3-7% of the users pay to have a better service, no commercials to interrupt the music, which balances out the rest of the free users. Similarly YouTube, Google-owned, announced this month the creation of a monthly paying platform, YouTube Music Key that will leverage the available music videos by offering off-line access and no commercials.

This raises the issue of the artists’ remuneration. Streaming platforms are known for not paying as much money as CDs sales would amount for. Nonetheless a website like Spotify pays royalties to the artists, 6 million dollars for Taylor Swift for instance, when she actually decided to withdraw all her songs from the platform antagonizing her 2 million followers. There is a lot of heated debates and ideology underlying the current transformation of the music industry.

Another current trend is to move away from computers to mobile. Each streaming platform has its app and new apps are developing to make it even easier to listen to music. No need to carefully plan playlists anymore, the app called Songza will do it according to the selected mood of the listener.

Finally mobiles are becoming remote controls to play music as the Apple TV for example allows the user to bring its own music to the screen and project it through its stereo system. In the same trend Sony created Sonos that allows the users to decide which song to play in which room wirelessly with wireless speakers from any device using any platform (streaming or iTunes). These are interesting ways for music appliance providers to compete.

Selling CDs cannot generate enough money for the industry to keep on relying on it. For instance the website Bandcamp bypasses the labels by offering a platform for independent artists to sell their albums in exchange for a 15% on sales. This could be an interesting intermediate model that makes the most of the possibilities brought by the Internet.

The current dematerialisation brings music back to the era before the recording technologies.

The main source of revenue now comes from concerts and artists who go on large tours more regularly. The show remains something valuable for the music lovers who are driven by the desire to live an exceptional experience, and attending concerts and festivals falls into that category. Labels are still key in the value chain as they have both an editorial role (bringing unknown artists to the front stage that the general audience might not have selected through social media channels) and a facilitator role (they take care of the logistics of the tours and planned the marketing strategy for their artists).

Another source of revenue comes from licensing as people are still in need of physical objects on which to project their love for any given artist. This trend overlaps with the collector behaviour of fans. It extends to the latest interest for vinyl. Special editions are even being recorded for today’s artists. Vinyl disks are considered to be beautiful objects, as opposed to CDs, and to be work of arts (jacket). The hipster movement embraced these objects and kept vinyl alive through stores raised to landmarks (Amoeba in San Francisco) or through events such as the Record Store Day, a celebration of music through vinyl invented in 2007 by independent stores, which generated 10 million dollars in 2013. Warner Music spotted that trend and launched the website www.becausesoundmatters.com, although they have not yet communicated on the sales generated on the website.

The solution for labels might be to get in the era of “free”. It will be very hard to get people who got used to having music for free illegally for lack of a structured paying alternative to join the paying model unless they sense a strong value proposition. Giving away things for free should be seen as an advantage for labels. The lost revenues are considered an indirect marketing campaign cost. Moreover the revenues saved for the consumers will be reinvested elsewhere (concerts for instance) and the industry as a whole is not losing money. For instance clips and concert videos posted on YouTube (and social media in general) generate viewership and in some cases a buzz that raises awareness on the artist more effectively than billboards, radio programmes and newspapers inserts. Similarly in the audio-visual industry, the producer of Game of Thrones was thrilled to see that his series had ranked first on the downloading platform, a key indicator of its popularity.

Pushing the model to its limits lead some artists to experiment. Madonna sold MDMA in 2012 has a bundle with her show, which meant that when there were no more tickets available CD sales dropped. Radiohead did a pre-sale of In Rainbows in 2007 on a “pick your own price” model before launching in commercially. They thus benefited from a large media coverage. Giving the choice to the customer increase the engagement and generates revenue.

Nonetheless such strategies can backfire as U2 experienced it when making a deal for the launch of the iPhone 6 to have Songs of innocence downloaded automatically on all 500 million iTunes libraries. This was perceived as intrusive and created a U2-bashing campaign on social media that was detrimental to the band image.

Moreover it fosters even more the tendency towards free of the users who lose perception of the value of an album. This devaluation of the work related to releasing an album means that people will not invest 10 dollars for a newcomer’s album when the hit singers give away their work for free. This could further destabilize the fragile balance between famous artists and newcomers within labels, if complimentary revenue streams were not emerging in parallel thanks to the Internet as mentioned previously.

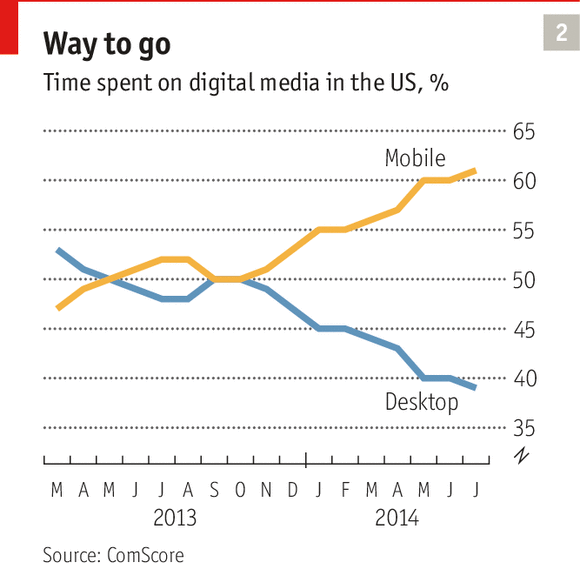

From computer to mobile

First we need to acknowledge a new trend: Internet users spend more and more time on their phones when surfing the web at the expense of their computers. That turning point happened in the fall of 2013 in the United States and is expected to happen in 2015 in the United Kingdom according to an article in the Economist issue of September 13th, 2014.

This means a whole different strategy for media content providers. The devices are smaller, and consequently the size of the screen, and the consumers have less patience than when they are browsing over their computer.

Therefore digital strategies need to evolve along these new lines when advertising in order not to antagonize users. Indeed 144 million people worldwide uploaded to their browser an adblock module that hides ads on computers according to the 2014 Adobe report.

There are at least two ways to go under the radar of web users: camouflage and targeting.

Camouflage

The idea for companies is to try and merge their advertising into the rest of the web. Native advertising tries to be less intrusive that classic banners and posters. Baby banners, for instance on the Angry Birds app, tend to take too much space and do not offer a great return considering that it takes a lot of space on mobile screen and that users feel trapped when they accidentally click on the link. The same “trapped” feeling arises when a commercial takes too long before you can click on”skip” on YouTube.

Camouflage on social media

On Facebook for instance,ads appear discretely on the side column or on the main newsfeed as recommendations based on the former clicks of the users. But the strength of social media is to make the users feel that they are the ones deciding what ads they want to look at. On a voluntarily basis users “like” pages of companies or “share” updates and “follow” companies and “retweet” their posts. That is the strength of social media and companies just need to be where the eyeballs of their customers are.

Camouflage through SEO

We could argue that it is no longer camouflage as to a certain extent everybody knows how the referencing system works on a web browser like Google works. The end goal is to arrive first on the result page of as many research keywords’ combinations. There are tricks to get to the top (the way the website is linked to others and the way it is built for instance), and there is also classic ad space that can be purchase to rank first and that are tagged with a yellow “advert”.

A new trend is appearing: inner referencing. People looking for a restaurant in San Francisco might as well type in their search engine “10 best restaurant in San Francisco” and let Google do its magic (after all we are all lazy). The results of such a search provides insights from established travel guides or newspapers… as well as websites dedicated to making rankings, on which companies pay to be ranked. A referencing site within Google’s referencing: the new Russian nesting doll.

Targeting

Geofencing

The location capability of mobile phones is an interesting feature for advertisers as they can keep track of their targeted market segment. For instance Pantene and the Weather Channel send relevant ads to customers depending on the current weather in their postal area or flower shops sending ads to customers within driving distance. This can be a dangerous game for these firms though. If the targeted customers realize how they have been played and how far the technology can go, they can have a negative reaction, feeling that these companies are invading their privacy too much.

Behavioral targeting

The idea in online advertising is not to target to the masses as a billboard in the street would, but to select a certain type of customers and target them thanks to a list of characteristics. Advertisers can thus hit the target more precisely and generate more revenue for their client. This is made possible by the amount of data that is collected thanks to cookies (see other post), web users now leave a trail of information behind them. A classic example would be the follow up email received the day after by customer having searched for certain products on an ebusiness website without yet purchasing it. Depending on people it will be perceived as either intrusive or considerate and convenient.

In a nutshell…

We thought watching the series “Mad men” had given us all the keys to advertising agencies… and yet this era seems to be centuries old. Advertising has taken the path of technology and we are not sure yet what will be the consequences. Finance took that turn decades ago and advertising is following today. Buying advertising space is made through programmatic bidding: computers enter a bidding competition after being programmed to purchase a given space thanks to the characteristics of a targeted group.

Hopefully the system will not derail as the finance did…

Source: the Economist special report “Advertising and technology”, September 13th 2014.

I have been wrestling quite a bit in the past months with the idea of the VOD being the new model to enjoy a movie… but I can’t get my mind around it. I am among the religious movie-goers for whom pressing pause, small screen, surrounding noise, comments would just kill the magic of that suspended moment that the film represents. But I need to step aside from my own habits to try and understand the current trend.

Context

Netflix’s arrival in France in September 2014 was synonymous of fear and regrets (for not having taken action earlier). Canal+ seems to have reacted best by improving its existing VOD offer, CanalPlay. We will see in the coming months how it is going to impact the theatre attendance levels. France is still a nation of movie goers as shown on the graph. The impact might prove stronger on TV watchers though as the setting is the same.

The movie experience

We are talking about two very different experience for the film viewer. In the theatre the viewer is surrounded by the reactions of all the other spectators. These reactions can go in the same direction or the opposite, fostering a sense of belonging for the former or a sense of misunderstanding/frustration for the latter. This interaction enriches the experience of the movie-goers as they share directly on the film in a way. Moreover the size of the screen (always bigger with IMAX for instance), the comfort of the chair, the lack of parasite noise and light (hence the disruption created by pop corn chewing or cell phone screens) contribute to making the spectators forget where they are in order for them to better merge with the film universe.

On the other hand the VOD offers a more practical experience: it is cheaper, there is no need to go out, it takes place at home (synonym of reassuring and comfy environment), there is no annoying spectator around and the movie can be paused at any time. This is certainly a valuable change in the film consumption habits as it becomes more accessible to more people. Nonetheless the magic dies with the ritual encapsulated in the “salle obscure”.

(NB: it is rather significant that the only word to describe the room where the movie is projected is called in English “theatre”, no magie in it compared to the French “dark room”).

The studio perspective

If the future of movies lies in the VOD then it means that they will be screened on computers or on home TV (that are getting bigger and bigger for that reason as well maybe). Would any studio be interested in investing millions in a movie to achieve a certain industry standard in terms of image quality, if it were to be only screened on such a small screen? Knowing that the past few years trend was, for the American majors, to produce more and more visual effects driven movies for booming budgets, will that model be sustainable without the theatrical release? For instance Amazing Spider-Man cost $258 millions… but it generated $890 millions worldwide in box office. This remains a dangerous bet and the loss can reach the hundred millions. For instance it amounted for $69 millions for the Green Lantern in 2011 for a production budget of $110 millions. Such an escalation of visual effects performance does not guarantee the success of films and the studios survive just by offsetting the loss of one movie with the success of another. It might have been the same business model all along, though this time the amount of money involved are quite different.

Shifting from the theatrical model to the VOD model is thus unlikely to take place all at once. Furthermore financing a movie with VOD revenue is impossible today. The revenue generated are too low and not indexed on the success of a film on the same scale (a successful film will cost more for Netflix to acquire, but not to the same extent as millions of spectators going to the theatre). As of today rules have not been set clearly on VOD, rules that would create a viable and durable model for movie financing.

What movie do we want to watch?

Eventually the question comes down to the kind of movie we want to watch. Blockbusters require (or seemed to require, it might evolve) large screens. These films, because they offer “new sensations” and are visually breath-taking, still attract people to the theatre. On the other side of the spectrum, the independent movies seem not to require such intensive technology and can be seen at home. This distinction is highly arguable. First it is a question of individual perception on the movie experience one is seeking. Second dividing movies along these broad lines of blockbusters vs independent movie (a term that refers to two very different realities in France and in the United States) is irrelevant.

Ultimately my concern is what kind of movie are going to be produced in the long term if VOD grows, what will be the impact of the introduction of such a technology/service on the offer of available movies. I strongly agree with Pauline Kael, movie critic for the New Yorker in the 60s and 70s, who bridges the divide between high brow culture and mass culture with the concept of entertainment. Movies should be entertainment and the stress should be put on the story. No matter how you categorize a film, and even how you view a film, as long as the story holds.

First let’s lay the foundation with some definitions.

You have probably noticed that your browser proposes you links to click on as soon as you start typing based on your previous search. You probably know that an algorithm on search engines for flight tickets remembers your search and enables the prices to go up if you do the same search again on the same computer. You might have asked your browser to remember your passwords out of convenience. But sometimes it feels that your web browser know maybe a bit too much about you…

This is all enabled by cookies. Cookies are small pieces of data sent from the website and stored in a user’s web browser while the user is browsing a website. The purpose is to facilitate web browsing for users. From the website owner’s perspective it represents a key marketing advantage. The user will be able to find again the items on his/her shopping cart, making his/her whole experience smoother. Moreover, the recommendations provided to the user and the pages displayed are shaped by the data collected on his/her previous activity, for instance on Amazon.com or even on Netflix.com. For more information on cookies: a simple explanation by the UK magazine Wired.co.uk

Data is power. The one who owns it acquires leverage. Web users are used to giving away data either to log into their account on a website or to have access to more promotions for examples. But where does that data go? How is it used? And in what form? The answer is “it depends”. It depends on the website and on the web browser. Sometimes the data is encrypted, sometimes it isn’t. Issues arise when there is an external usage of that data, particularly when it is sold to third parties. Because of the lack of transparency and privacy breaches which occur too sporadically to lead to meaningful change, users do not hold websites accountable. It seems to be too vague an entity to know exactly who to target, although larger companies like Google receive a lot of focus. A “Michelangelo moment” (1) according to the Economist issue of September 13th 2014, would most likely change the current statu quo and result in a drastic backlash… but such a privacy breach has not happened yet.

Recently users have been asked to “opt in” on each new website they visit, that is to say to allow cookies to collect data while browsing on the site. Websites operating in Europe were forced into converting their cookie policy from “opt out” to “opt in” by a European directive so-called the “Cookie Law”.

But where is the “no” button? Who has really read everything after clicking on the “more info” button? Signing out of newsletter is already a tedious process, and “opting out” of cookies is even more so.

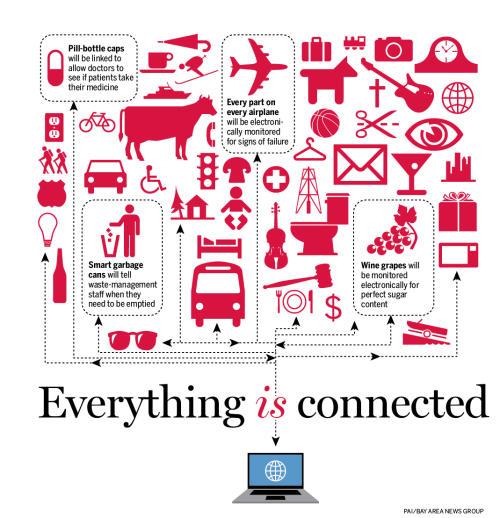

The impact of connected objects

What is now often called “connected objects“, “smart objects” or “the internet of things” includes all the objects that are connected thanks to the cloud and are thus able to collect data. For instance, a Tesla car equipped with a software to notify the customer when a repair is necessary, a Ralph Lauren polo which records calories burned and heart rate and sends them to your smartphone, or a Philips light bulb controlled via tablet. These type of objects where once regarded as gadgets, though views are evolving and they may soon become the norm.

But at what cost? The fear is that with these connected objects our every move will potentially be recorded. The third party usage of this data becomes a central issue, because some data might be interested if shared, for instance driving conditions for other drivers.

A solution proposed in the November 2014 issue of the Harvard Business Review would be for companies to sell “binding or aggregate data on purchasing patterns, driving habits or energy usage” rather than individual customer data..

In the same issue, Alex Pentland draws the structure of a “New Deal on Data”. The idea is “to give people the ability to see what’s being collected and opt out or in. (…) It’s a rebalancing of the ownership of data in favor of the individual whose data is collected. (…) People are ok about sharing data if they believe they’ll benefit from it and it’s not going to be shared further in ways they don’t understand.” Such works are key to drive awareness and to lobby governments toward these best practices. Transparency will foster trust among Internet users.

In the near future, new legislation will need to be passed by regulators to ensure privacy while using connected objects. The debate is always the same: do we let companies regulate their websites themselves or do regulators need to intervene? Companies have every reason to change their operating model as it is costly to collect all the data they can (all the more because not all data is relevant), and dangerous as their systems could be hacked resulting in massive privacy breaches and countless headaches.

Nonetheless the status quo remains and a bigger push from regulators, consumer groups and citizens is necessary.After all, we should all as citizens and web users feel involved with the issue.

For more information: the interview of MIT professor Alex Pentland.

Story written by Raphaelle Chaygneaud-Dupuy

(1) In 1992, the Michelangelo virus widely infected software and pushed people to invest in anti-virus software.