This post explores the manual production of a potato stamp to print a five-letter word. This exercise provided an opportunity for me to consider the time, labour, and resource costs involved with producing text in a way that pre-dates the mechanized printing process.

Production

With Juniper’s (2015) video as a guide, the process of carving and printing my own name using potato stamps took me about an hour and a half. I decided to use sans-serif letters for my letters, hoping it’s simpler shape and form factor would save me time and work. However, even with the letters outlined on the potato, I found the process of carving out even and consistently sized letters a time consuming challenge.

Given the somewhat unforgiving nature of working in this way, I resorted to working my mistakes into the design of each letter, using whatever part of the potato was still left. This process of trial and error led to some mixed results, but by the time I got to my second set of stamps, I noticed a slight improvement in my technique. This iterative process made me think of the ‘fail and try-again’ approach supported at the makerspace where I work. Here, students are encouraged to create, assess, and improve upon their prototype designs using tools like 3D printing.

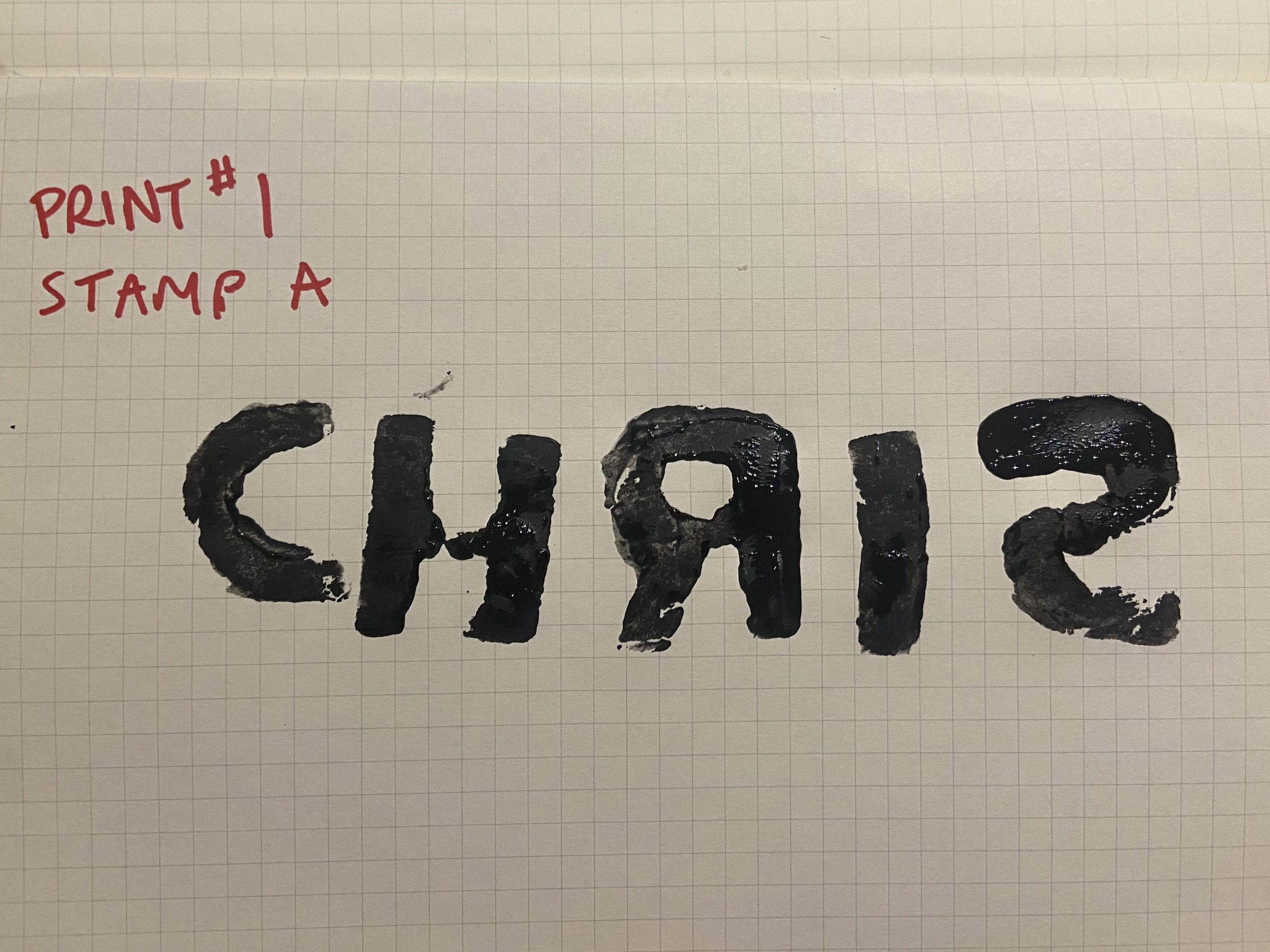

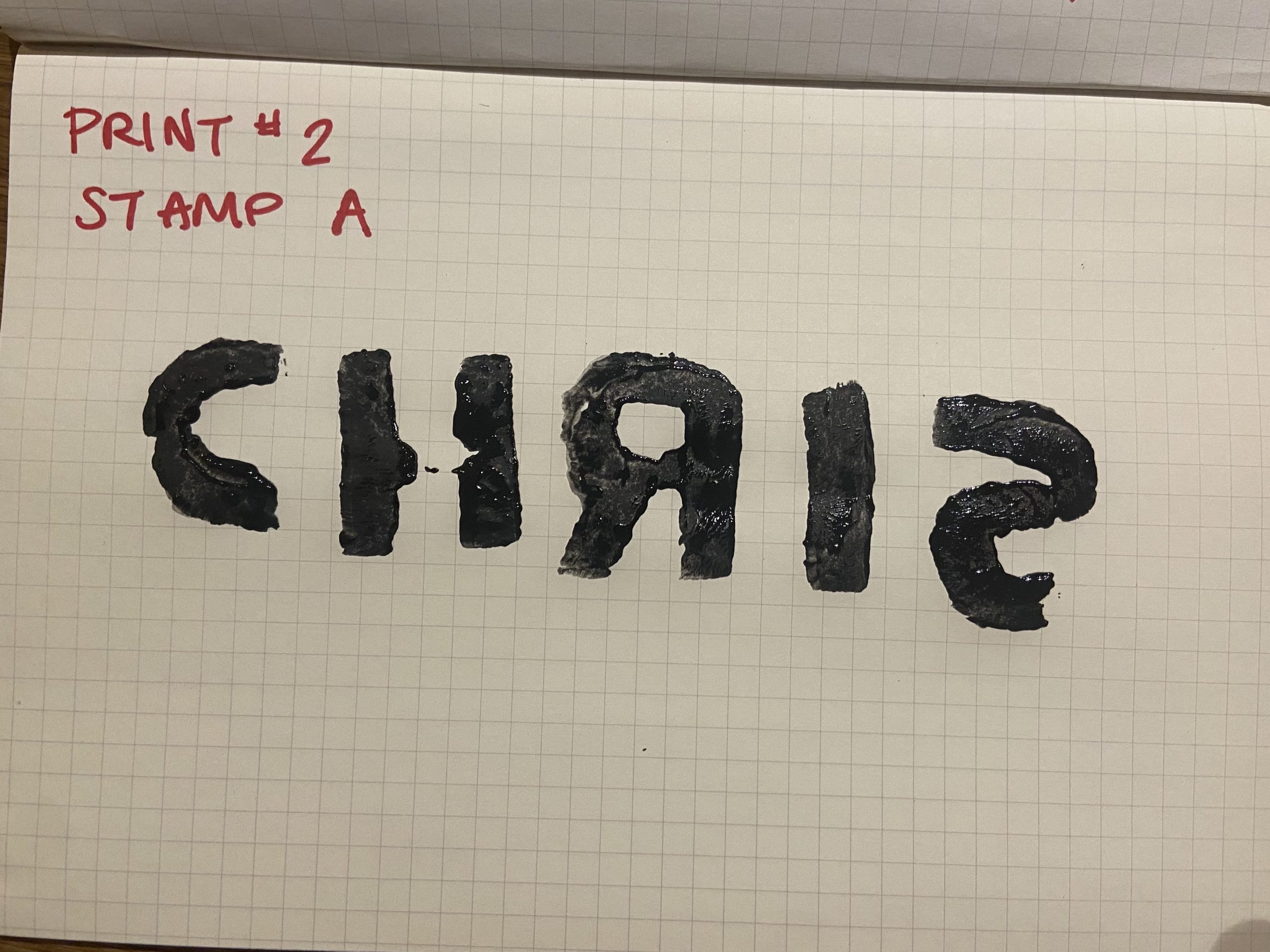

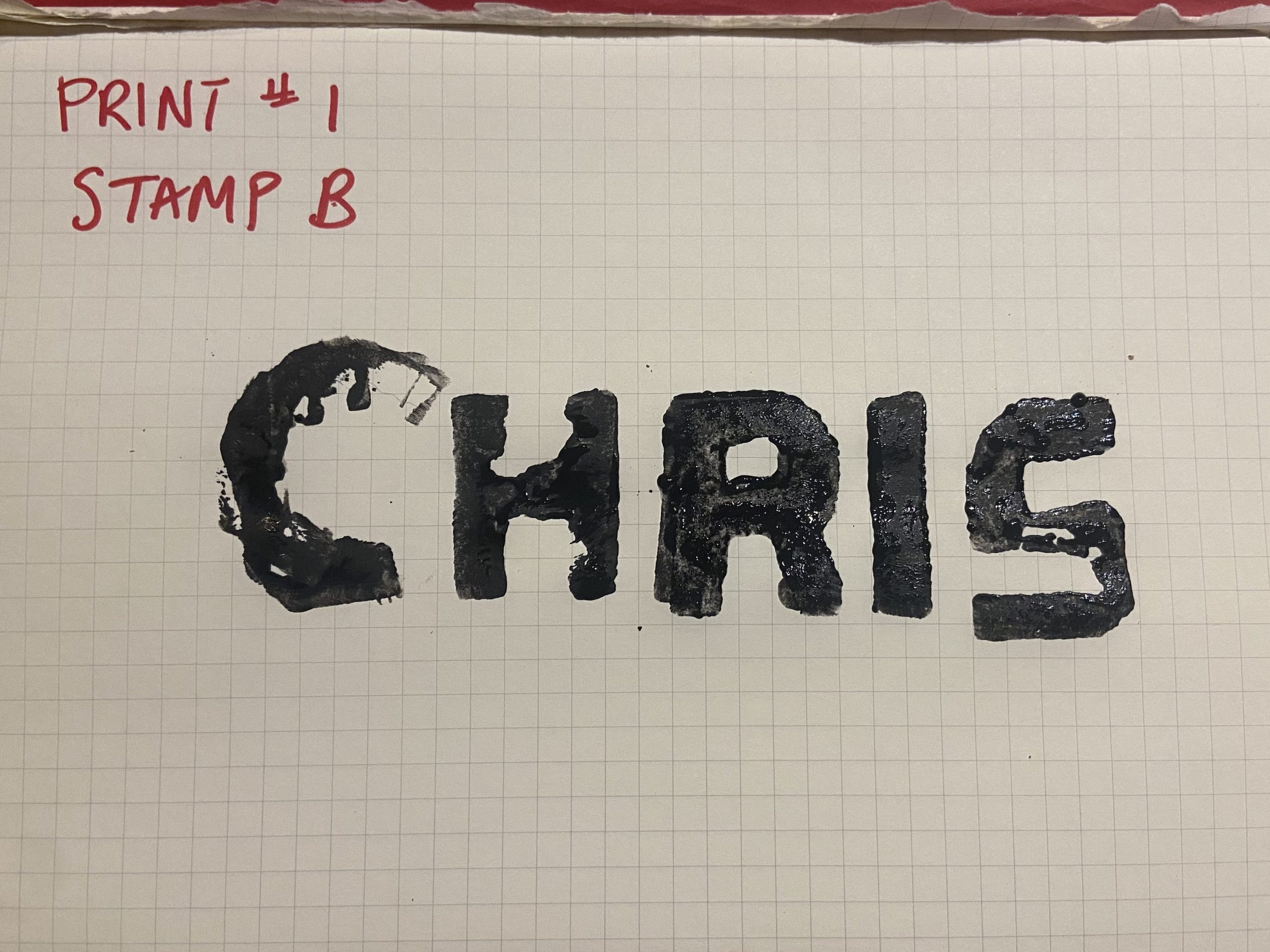

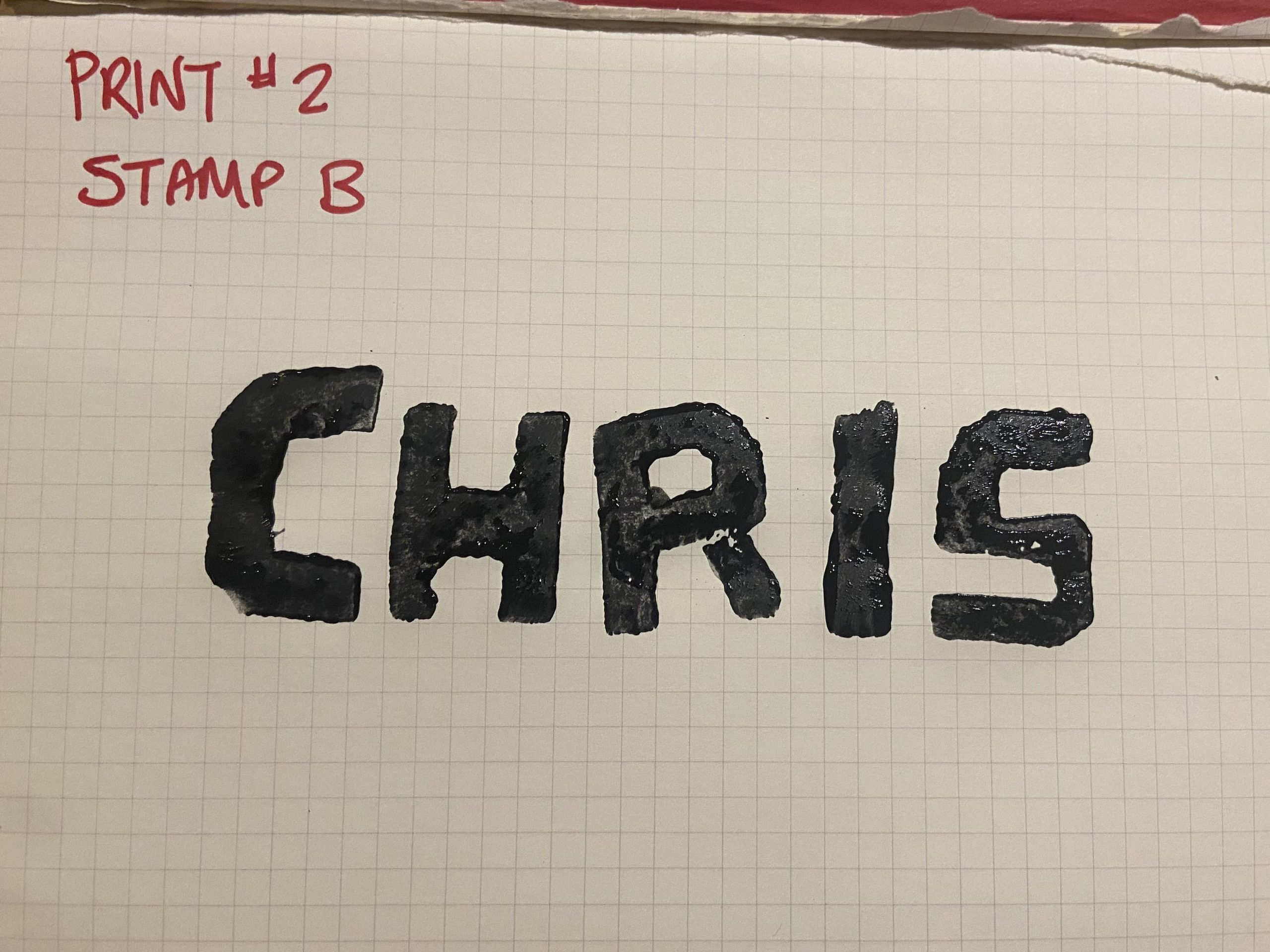

The top row is my first attempt (‘Stamp A’), and the bottom row is my second (‘Stamp B’).

Upon completing my first set of stamps, it immediately occurred to me that I forgot to mirror the letters ‘R’ and the ‘S’. I spent so much time focusing on the shape and quality of each letter, that I didn’t think ahead to what it would look like once printed.

Once I got around to printing, I found it challenging to maintain the spacing and rotation between each letter. I also noticed the quality of the letter varied due to my uneven cuts and inconsistent use of pressure when applying it to the page. As such, the paint on some letters did not transfer well (e.g., the crossbar on the letter ‘H’). In retrospect, I might have had better results had I carved the letters onto a single block. However, with the smaller size potatoes that I had on hand, I decided to keep going with individual letters.

During my second round of stamps, I corrected the orientation of the letters ‘R’ and ‘S’ and spent less time fussing around with carving each letter shape (having now had some practice). While printing, I accidentally smudged the letter ‘C’ by pressing too hard. Once again, the letter and spacing between letters were inconsistent despite my best efforts. Nonetheless, I was happier with this second attempt.

Reflection

This potato stamping exercise reminded me of my first printmaking experience in the 11th-grade, where I learned to carve and print designs with linoleum blocks. Back then, my approach to printmaking was solely for artistic purposes, rather than a mode of producing and conveying written information. As such, any imperfections made along the way were insignificant and could be perceived as enhancing the aesthetic quality of the work. This time, when using this method to approach writing, greater attention to form and structure was necessary to ensure that the written word can be perceived clearly and accurately. In the case of my potato stamps, this extra attention to detail resulted in additional time and work. To use this method to produce an entire text seems onerous and impractical; especially when compared to the efficiency and accuracy afforded by mechanized (and later digital) print technologies.

It also seems that the manual printing process comes with additional resource-costs when compared to mechanized methods. As my experience would suggest, there is an increased margin for human error, for example: applying too much (or not enough) pressure; forgetting to mirror letters; misjudging the spacing between letters; etc. In my case, each misprint resulted in additional consumption of physical materials such as paint, paper and the relief medium itself. While not without its own disadvantages, it seems the increased accuracy and uniformity of mechanized printing methods (as demonstrated in the letterpress video by Danny Cooke [2012]) would minimize the margin for error, resulting in fewer wasted resources.

With all of these factors in mind, it’s difficult to imagine that manual printing would have been successful in the same way that mechanized printing was in improving literacy and knowledge access. Lamb & McCormick (2021) notes that mechanization, coupled with advancements in paper technology, made it easier, faster, and cheaper to produce written materials (00:43:00). The impact that this had on literacy is especially significant when viewed through the lens of power and social change, given that reading/writing literacy has been considered a tool for challenging oppressive power structures (thinking of Paolo Freire’s work on critical pedagogy) (Smidt, 2014).

References

Cooke, D. (January 26, 2012). Upside down, left to right: A letterpress film. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/n6RqWe1bFpM

Juniper. (August 3, 2015). Revamping your stuff with potato stamps. [YouTube]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRKyECgL1wY

Lamb, R., & McCormick, J. (Hosts). (2021, May 15). From the vault: Invention of the book, part 2. [Audio podcast episode]. In Stuff to blow your mind. iHeart Radio. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/stuff-to-blow-your-mind-21123915/episode/from-the-vault-invention-of-the-82564254/

Smidt, S. (2014). Introducing Freire: A guide for students, teachers, and practitioners. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315777634

Hi Chris,

Your execution of this task was quite thought-provoking for me. I have linked to it here:

https://blogs.ubc.ca/etec540lyasin/2023/04/07/link-2-chris-rugo-task-4-manual-printing/

Thank you!

l.