This week’s task involved engaging with a simulation called Detain/Release (Porcaro, 2019), which involves taking on the role of a pre-trial judge and ‘ruling’ on 24 simulated cases. Rulings are based on simulated defendant profile, scaled AI risk assessments, and prosecution recommendations.

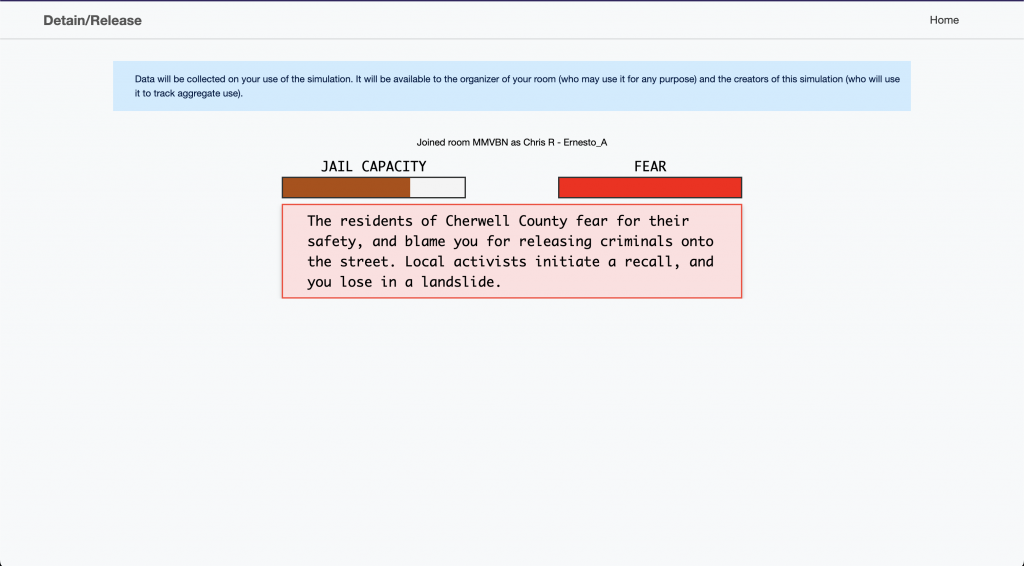

I attempted the simulation twice, as my connection failed towards the end of my first attempt. On my second attempt, I got as far as 21 rulings before receiving the following message:

Detain/Release proved to be a bit of an ethical challenge for me as I made my way through the simulated rulings. My own personal thoughts on the U.S/Canadian criminal justice system aside, there was too little information available through the interface to further contextualize the risk assessments generated by the simulated AI system. In particular, there were no controls available for me to review the source information that informed the AI’s risk assessment. As someone who prefers to make informed decisions, the broad categorizations of ‘crime’ and the lack of transparency afforded by the system made me feel uncertain and apprehensive when ruling each case. Most of the time, I found myself disagreeing with the simulated prosecutor’s recommendations to detain for cases that didn’t involve violent crime. In retrospect, this is likely why I lost before the 24 rulings were up.

This simulation made me think more deeply about the role that algorithmically powered decision-making technologies play in the criminal justice system; and specifically, crime prediction tools that are used by both Canadian and U.S. police institutions (O’Neil, 2017; Robertson, Khoo & Song, 2020). Given that AI systems are trained upon large data corpuses inputted by a system architect (Storied, 2021, 07:16), the question becomes who is or isn’t represented in each corpus, and what kind of biases shape them. This becomes further problematized in the context of the criminal justice system, an institution that has a long history of systemic racism (House of Commons, 2021), where inaccurate and biased data sets are being used to make high-stakes predictions and risk assessments (O’Neil, 2017).

In their TED article, O’Neil (2017) unpacks the implications that police bias in data has had in multiple police jurisdictions across the U.S. In particular, O’Neil (2017) describes how neighbourhoods with low socioeconomic status are overrepresented in many data sets due to the policing of minor “nuisance” crimes in these neighbourhoods. O’Neil (2017) goes on to address how data points associated with minor crimes tend to skew the predictive models, thereby perpetuating a “feedback loop” of over-policing in low-income, racialized communities. While reading O’Neil (2017), I’m also reminded of a UN report that found the unregulated use of AI technologies in policing and immigration, such as facial recognition, is at risk of violating human rights policy by way of reinforcing racist and xenophobic biases. (Cummings-Bruce, 2020).

In the context of education, there has been an uptake of algorithmically-powered technologies to support automated assessment, writing, and proctoring. Furthermore, there has been interest in how GPT models will play a role in pedagogical practice and academic integrity. As AI-powered tools become more ubiquitous in education, there is a need for greater scrutiny on the part of practitioners to understand whose data is being used and how. The presence of oppressive algorithmic systems is not just limited to policing. In the podcast 25 Years of Ed Tech, Pasquini and Gilliard (2021) discuss how a risk assessment tool was widely adopted across U.S. schools with little training and oversight, and used biased data sets to disproportionately categorize racialized students as ‘at-risk’ (17:40). Much like the policing prediction models explored in this unit, AI tools designed for education (especially ones related to high-stakes assessment) can perpetuate harmful outcomes for equity-deserving groups. There is a clear need for educators to develop critical pedagogical practices and understand around how these tools operate.

References

Cummings-Bruce, N. (2020, November 26). U.N. panel: Technology in policing can reinforce racial bias. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/26/us/un-panel-technology-in-policing-can-reinforce-racial-bias.html

House of Commons. (2021). Systemic racism in policing in Canada. https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/SECU/report-6

O’Neil, C. (2017, April 6). Justice in the age of big data. TED. Retrieved August 12, 2022. https://ideas.ted.com/justice-in-the-age-of-big-data/

Pasquini, L. & Gilliard, C. (Hosts) (2021, April 15). Between the chapters #23 looking in the black box of A.I. with @hypervisible (No. 52). [Audio podcast episode]. In 25 Years of Ed Tech. Laura Pasquini. https://25years.opened.ca/2021/04/15/between-the-chapters-artificial-intelligence/

Porcaro, K. (2019). Detain/Release [web simulation]. Berkman Klein Center. https://detainrelease.com/

Robertson, K., Khoo, C. & Song, Y. (2020, September 1). To surveil and predict: A human rights analysis of algorithmic policing in Canada. The University of Toronto Citizen Lab. https://citizenlab.ca/2020/09/to-surveil-and-predict-a-human-rights-analysis-of-algorithmic-policing-in-canada/

Storied. (2021, May 5). From Alan Turing to GPT-3: The evolution of computer speech | Otherwords [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/d2UccTPnl4w

Hi Chris, Your connection with our Detain/Release activity to AI-powered technology in education is very interesting. ChatGPT, Bing AI, and other tools are readily available, and students know they exist. The original intent of ChatGPT was to assist humans with “composing emails, essays, and code” (Ortiz, 2023). Did they program ChatGPT to do this because they realized humans have the most difficulty completing these tasks? The invention may not have come with ill intentions, but humans can definitely take advantage of these tools. You mentioned that students have to complete high-stakes assignments. If students were using AI systems like ChatGPT to complete these assignments, would it take away from their ability to think like their authentic selves? Would creativity exist? I recently joined a recreational sports team, and we had a tough time designing our jerseys. Someone on our team had access to the premium version of Bing AI, and he gave us parameters for Bing AI to design a team logo for us. What happened in the days when we designed with our creativity instead of depending on other sources?

Reference:

Ortiz, S. (2023, March 23). What is CHATGPT and why does it matter? here’s what you need to know. ZDNET. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-chatgpt-and-why-does-it-matter-heres-everything-you-need-to-know/

Hi Chris,

This was an interesting insight into how other people approached the task of Detain/Release. I, too, was accused of being too lenient and producing ‘fear’ amongst the citizens of the city during the simulation. The problem that I struggled with as well was trying to make a decision using limited information.

Interestingly enough, in a book I read this summer called Talking to Strangers by Malcom Gladwell, they analyzed the decision making outcomes of judges in NYC. Even though the judges had considerably more information than an algorithm, the judges had a significantly worse outcome than if an AI generator had determined whether an offender would re-offend. The AI predictor that they built put over 500,000 cases through it with the command to make a list of 400,000 who could be released on bail (with the same information that the courts had). The people on the computer’s list were 25% less likely to commit a crime while awaiting trial than the 400,000 people released by the judges of New York City. Sadly, as Gladwell concluded “machine destroyed man”. It certainly leaves us with a lot of questions! Where do we go from here?