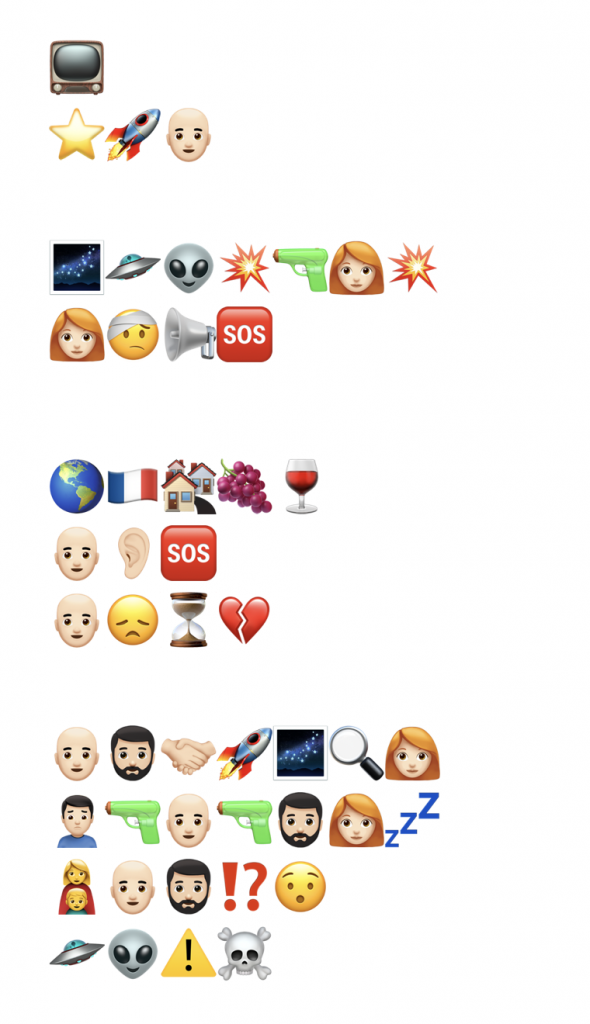

Link to Original Post: Task 6 – Emoji Story (Young, 2023)

Comment

Hi Jessie!

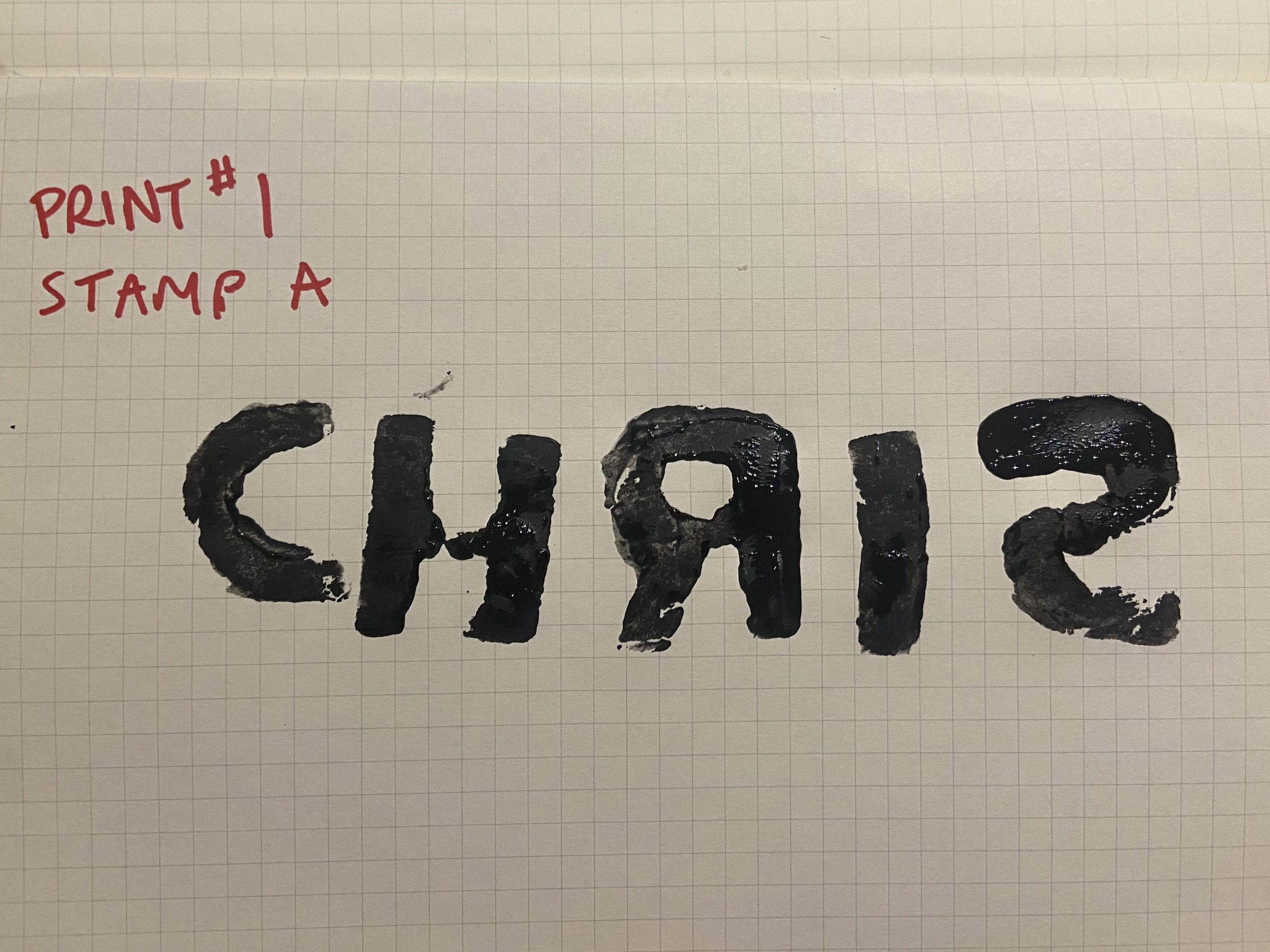

Your emoji story wouldn’t happen to be The Last of Us, would it? I’m basing this on the mushroom and zombie emoji in the first line, as well as the game controller emoji next to the film clapper board (given that the show is based on a video game).

In addition to exploring the various cultural interpretations of visual symbols and gestures, you note how emojis appeared differently when viewed on a different device. Miller et al. (2016) suggests that cross-platform differences in emoji can result in miscommunication, such as misinterpreting the emotional sentiment behind someone’s use of emoji. In one particular example, Fedewa (2022) illustrates how the frowning emoji on an Apple device is represented with a more angrier looking emoji on a Samsung device. It’s clear how the differences between the two can significantly change the emotional meaning of the original message for the recipient.

Having switched between Android and Apple devices over the years, I can understand how frustrating this cross-platform variability be when it comes to writing/receiving messages with emoji. In fact, it’s partly why I decided to take a screenshot of my own emoji story, so that it would be represented exactly as how I see it on my own device. Given the unlikelihood of a universal cross-platform emoji set, Miller et al. (2018) proposes tools to help users preview what their emojis would look across platforms to help mitigate miscommunication/interpretation. As someone who values intentionality in how I communicate with emoji, I would love to see this become a standard feature across all devices. Thanks for sharing!

Reflection

I enjoyed the opportunity to engage with Jessie’s post. Her reflection gave me some pause to ponder about cross-platform variability when it comes to emoji – and how this can lead to miscommunication. I explored this a bit further in my comment to her post, which I’ve included above.

Another point within Jessie’s post that I could related to were her challenges with finding emojis that were representing some of the themes in her story, such as action verbs like “bite” or “eat”. I, too, shared in my own post how it took time to find emojis that could capture my intended message and meaning on it’s own and how I usually rely on written text to contextualize some of the use of my emojis. I appreciated that Jessie explored the notion of context further by discussing cross cultural interpretations of visual gestures and symbols communicated through emoji. I’ll admit that this didn’t occur to me until after I finished writing my emoji story.

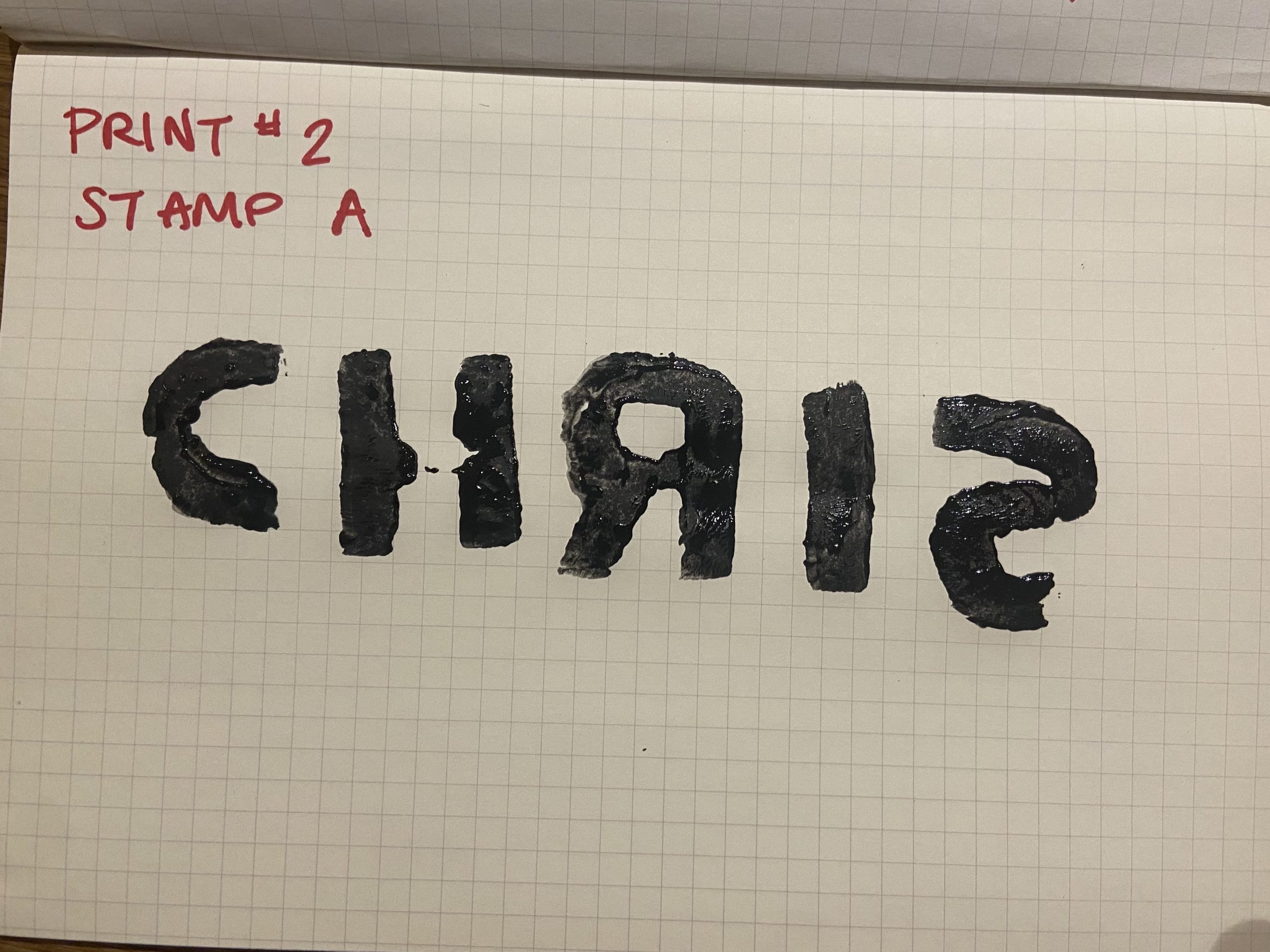

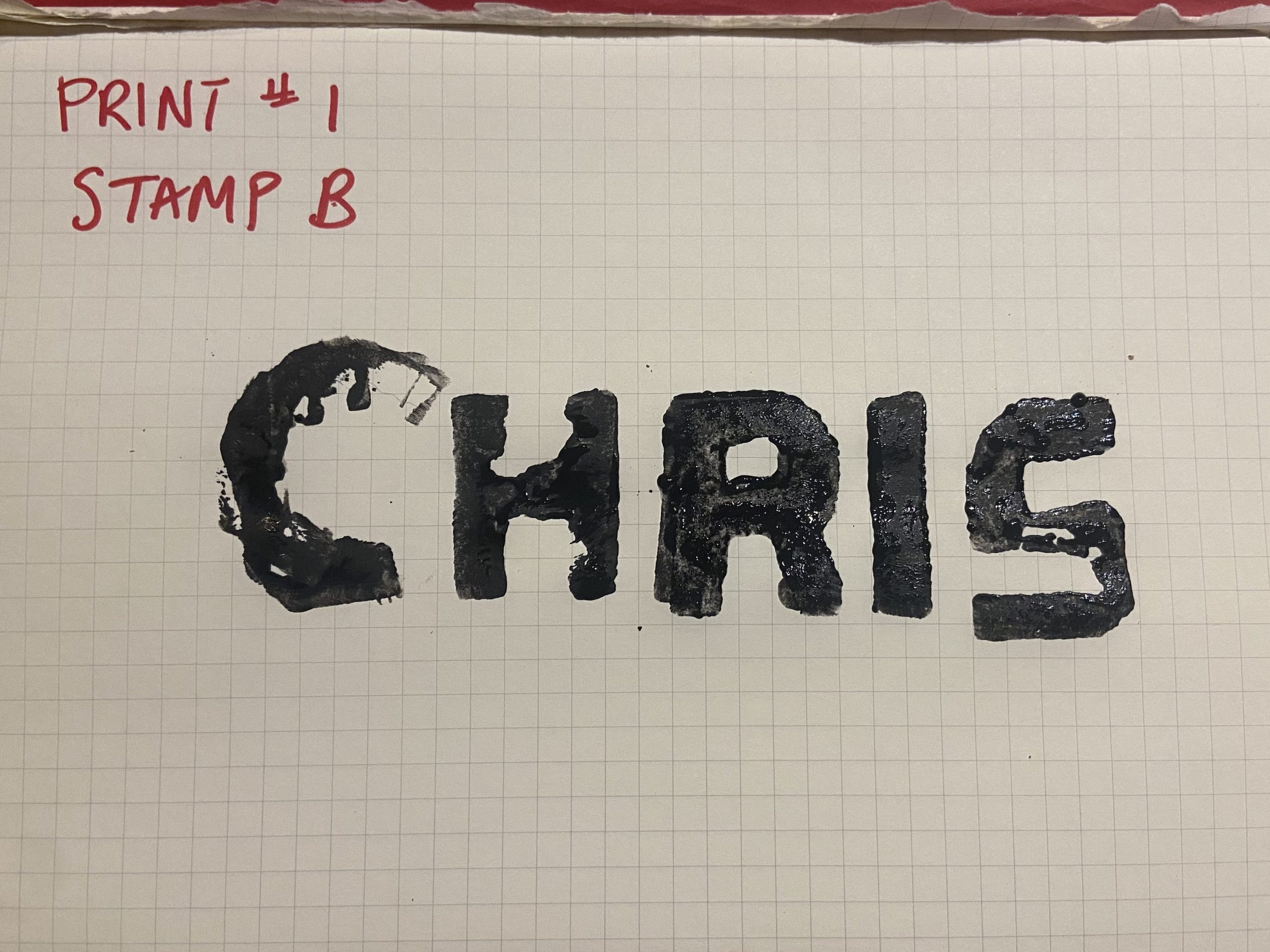

Upon further examination with Jessie’s post, it appears that we have utilized very similar tools and modes of manifesting our work. We both shared our posts through UBC Blogs and used a conversational tone in written English. We both structured our posts similarly by starting with our emoji story and proceeding to reflect on the process. In terms of differences, it seems that I used a more hierarchical approach to my writing with the use of headers to organize different parts of my reflection. I also noticed that my emoji story is shared as a screenshot image, taken from my Mac’s text editor – while Jessie’s emoji story is shared as actual in-line text (as in I can highlight the individual emoji characters). I think this explains why some of Jessie’s emojis are rendered differently on my screen – which exemplifies some of the cross-platform variability that Jessie hinted to and that I expanded on further in my comment.

References

Fedewa, J. (2022, February 11). That emoji might not look the same on your friend’s phone. How-To Geek. https://www.howtogeek.com/784832/that-emoji-might-not-look-the-same-on-your-friends-phone/

Miller, H., Thebault-Spieker, J., Chang, S., Johnson, I., Terveen, L., & Hecht, B. (2016). “Blissfully happy” or “Ready to fight”: Varying interpretations of emoji. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 10(1), 259-268. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v10i1.14757

Miller, H., Levonian, Z., Kluver, D., Terveen, L., & Hecht, B. (2018). What I see is what you don’t get: The effects of (not) seeing emoji rendering differences across platforms. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 2(CSCW), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3274393

Young, J. (2023, February 19). Task 6 – emoji story. Jessie Young – ETEC 540. https://blogs.ubc.ca/jessieyoung540/2023/02/19/task-6-emoji-story/