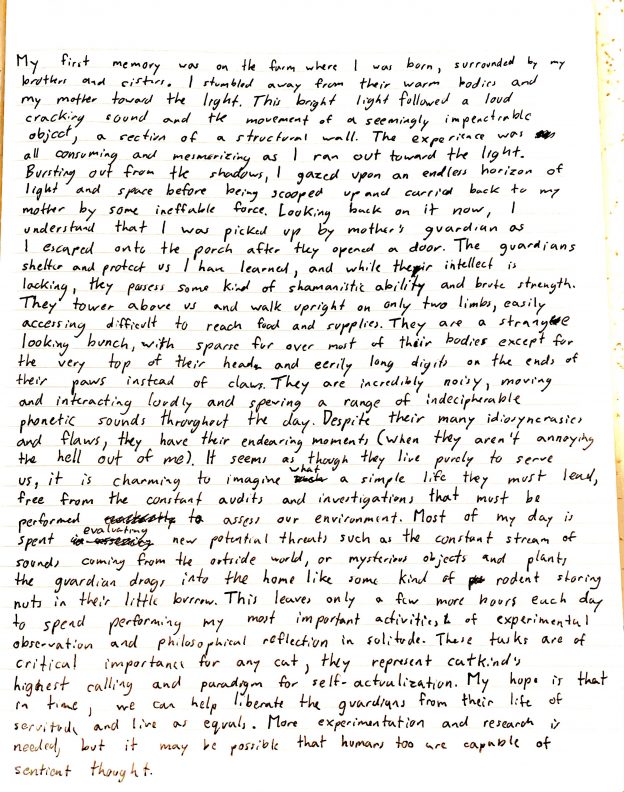

Okay, so this is a story about a time when I thought I might not survive. So it starts when I was on vacation probably 10 years ago, in Brazil. And so me and my partner at the time were in southeast Brazil, staying on a small island called Elliot don’t Mel. And it was really beautiful place. There are tons of mosquitoes and really nice beaches. But anyway, anyway, there was a cave on the south part of the island. And so it’s really tiny islands, you could walk down there. And it only took a couple hours. And so we decided to walk down to go see this cave. But thing we didn’t realize was that the only way to get from the north to the south part of the islands by foot, if you didn’t have a boat was to go along this this jacket rock path that was right on the beach. And so you had to go when the tide was out, because if the tide was high, you wouldn’t be able to cross or go back. And so not knowing this, we went down to the cave. And it was beautiful, Texan pictures. And out of nowhere, this huge Tropical Storm blows in. And suddenly, it’s torrential downpour. And everything is drenched. There’s lightning. And we could tell it was getting pretty bad. It’s the lightning was like every few seconds. And so it’s dark, we’re wet. And we’re just sort of stuck on this beach. And so we’re trying to get back and to go back to the north part of the islands where our hostel is we have to go over that path. And we didn’t realize that now the tide had risen and so we weren’t able to just walk back anymore, we had to swim and actually go in the water to get back and we would have just waited out the storm but we also were running out of daylight and it was starting to get dark and so we had to walk through quite a bit of jungle forest to get back still and so we knew that we had to get back before the sunset completely or else we would be lost in the jungle on this island. And so so we start trying to find our way along this path through the water and kind of realize that the only way to do this is to actually go all the way into the water and and yes we had bags it’s like cameras and things like that in them and I’ve got fat is screaming and crying. And we go into the water and I toss her the backpack and it floats out to sea so that I could go dive in and grab this backpack with all of our our stuff in that cameras and bring this back and the waves are crashing right beside us into the rocks and there’s lightning every two seconds splashing around us. And I thought I don’t know if I’m going to die here get electrocuted or get pulled out into the water drown or get lost in silence but after this for five minutes of terror We made it to the other side and hurried back to make her way back to the hospital

How does the text deviate from conventions of written English? In what ways does oral storytelling differ from written storytelling?

Speech is non-grammatical, it is ephemeral and challenges the sense of time and space of conventions of the literate world. While written English is material as described by Haas (2013), “having mass or matter and occupying physical space” (p. 4), and endures through time, oral speech lasts an instant and floats through the air, leaving no trace except memory. As someone growing up in a literary world, the term “subtext” comes to mind; oral storytelling comes with a rich “subtext” of layers of meaning beyond what is spoken. For example, in telling this story I am presumably in some social situation speaking directly to another person, the story is inextricably wrapped in layers of situational context that are unclear from this passage. Questions must be asked of this text to understand it such as:

-

- Why am I telling this story?

- What situation am I in while telling this story?

- Who am I speaking with?

- What do I really want the person I am speaking with to know about me?

- What am I really saying about who I am as a person and my relationship to the other person?

In a literary work, an author would necessarily explain important contextual factors and relationships in writing, making them seem definite and absolute. With oral storytelling, situational factors are often more ambiguous and unclear, rules are not set in stone and can change ad hoc.

The socio-culturally agreed upon grammatical rules of a language are not rigidly applied to spoken language, at least in part because of the nature of oral storytelling, “a spoken (or mentally composed) message unfolds in time” (Gnanadesikan, 2011, p. 3) whereas writing places messages in space. Writing inherently implies permanence, but oral speech is a moment becoming a memory in real time, free from the mechanistic structures of physical objects.

What is “wrong” in the text? What is “right”? What are the most common “mistakes” in the text and why do you consider them “mistakes”? What if you had “scripted” the story? What difference might that have made?

First, there are a number of both informal and formal grammatical rules of written English that are broken by the text from my oral story. There are many redundant words, missing prepositions, run-on sentences, and non-grammatical sentence structures. Sometimes the subject of the sentences is unclear. Additionally, many of the terms and phrases did not translate over accurately which led to some humorous results:

-

- Elliot don’t Mel

- Jacket rock

- Texan pictures

- Back to the hospital

The island was called Ilha do Mel, I was describing jagged rocks, we were taking pictures, and we went back to the hostel. Some of these miscommunications might be quickly translated by someone through inductive and deductive reasoning given the rest of the information available, but some could lead to very confusing interpretations. For example, the location is important; if a reader is from the region they might be confused and distracted by this confounding information. More seriously, the interpretation of hostel to hospital at the end of the text following the sentence about my fears of death might lead a reader to question my safety and health.

Secondly, the information in the text might be “wrong”, meaning inaccurate. I was not from the island, and did not speak Portuguese, there very well could have been a safer way to get back to the hostel. However, when telling this story I presented my experience as fact, because at the time it was what I was thinking and feeling. This presents another difference between oral and written texts, if I had scripted this story I might fact check it, edit it multiple times, curate my selection of words. I would scrutinize it to the standards of the written world before sharing it and mechanize my speech to make it free from errors. I would care about the accuracy of my words because I would fear judgement and know that my words would become lasting tangible reality. Orality on the other hand is based in memory and lived experience, it emphasizes sharing subjective realities better than material facts. This is a strength of orality in its ability to persuade and evoke emotion.

Last year, I began creating closed captions for videos for work to help improve accessibility. This practice has significantly changed my awareness of the differences between literary text and orality. I have come to understand that natural oral speech is non-grammatical, often containing stutters, non sequiturs, lengthy run-on sentences and filler words or phonetic sounds that contain no dictionary meaning. Taking this class, I now find the term “non-grammatical” to be quite intriguing. I learned this word as a common way to describe how people talk among the closed captioning community. This relates to Ong’s (2002) discussion on how literate culture understands orality in terms of how it is not literate (pp. 11 – 13), completely missing the point that orality preceded written literacy. Captioning is an exercise in taking something which can not be fully understood in a written form, and documenting it anyway because this is the best solution we can come up with.

There have been times when I am captioning where a sentence that I thought sounded completely reasonable becomes nonsensical after looking at it through the lenses of grammar and written definitions, highlighting the powerful impact of tone, pitch, body language, and other unwritten cues for conveying meaning. Orality can convey emotional meaning and a sense of interpersonal understanding in a fraction of the time that it would take to explain and interpret through written text. I do not see the non-grammatical errors in oral speech as mistakes, rather as an entirely different way of being and communicating.

References

Gnanadesikan, A. E., & Wiley Online Library. (2011;). The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the

internet (1. Aufl. ed.). Chichester, U.K;Malden, MA;: Wiley-Blackwell.

Haas, C. (2013). Writing technology: Studies on the materiality of literacy Taylor and Francis.

doi:10.4324/9780203811238

Ong, W. J., Taylor & Francis eBooks – CRKN, & CRKN MiL Collection. (2002). Orality and literacy:

The technologizing of the word. London;New York;: Routledge.