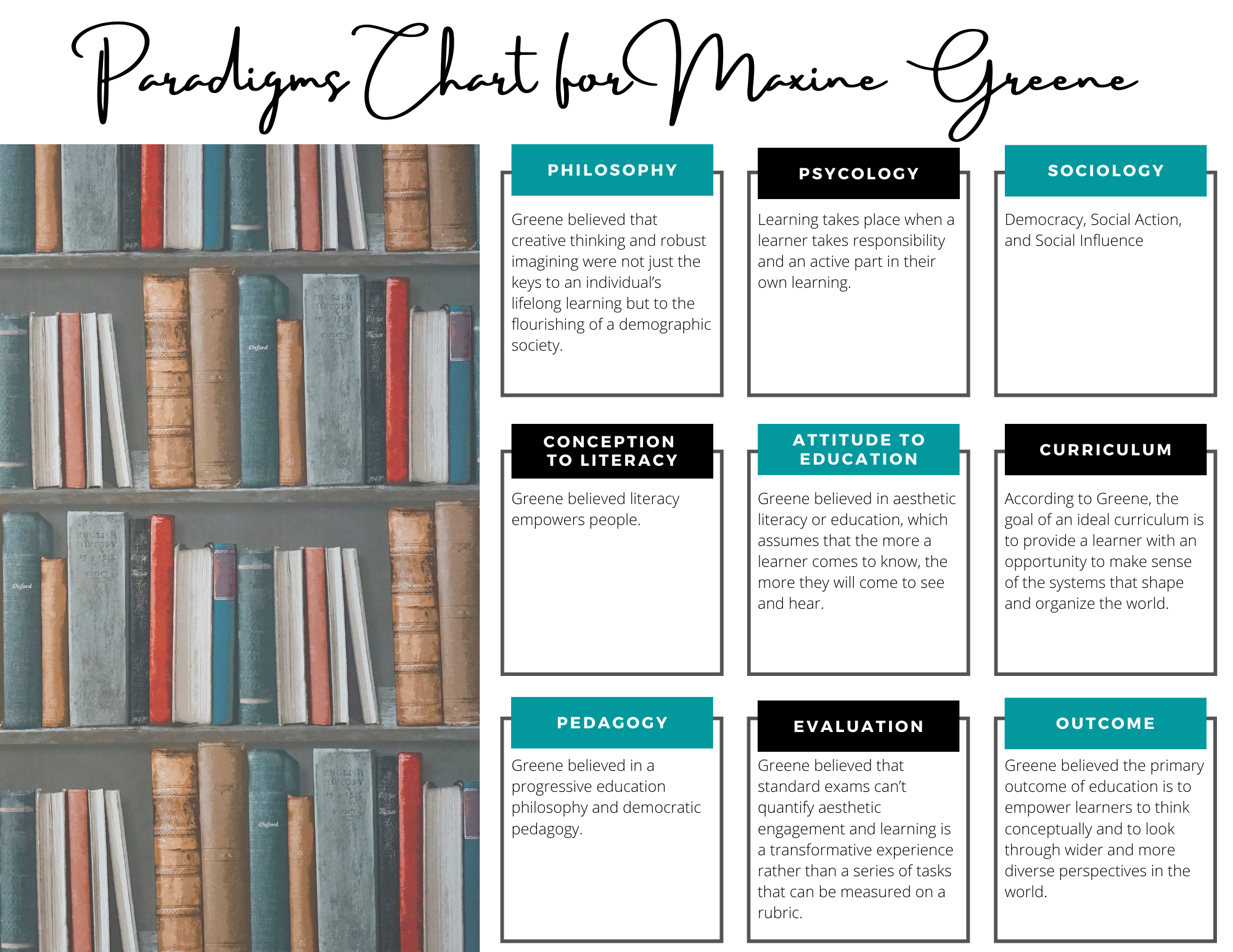

Educators have come to view literacy as a set of context-neutral, value-free skills that are imparted on learners (de Castell and Luke, 1983). Below is a paradigm chart outline Maxine Greene’s educational theory. To develop this chart, I used de Castell and Luke (1983) as a model. De Castell and Luke identify three paradigms of literacy: the classical, the progressive, and the technocratic (de Castell and Luke, 1983). Maxine Greene theories fall in line with progressive reform, where literacy attempted to address the practical speech of everyday life, child-centered curriculum replaced the classical, and the normative stress moved moral and cultural edification to socialization and civic ethics (de Castell and Luke, 1983, p. 89). Looking at de Castell and Luke’s (1983) paradigms chart, I think we would add a fourth paradigm of literacy: the Indigenous paradigm. This theory would include ontologies rooted in worldviews that we are all related to each other, to the natural environment, and to the spiritual world and epistemologies that are emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and physical, which are informed by ancestral knowledge and passed on through storytelling to younger generations.

I enjoyed this intellectual production and enjoyed watching Maxine speak about education and her experiences.

More about Maxine Greene and the Paradigms Chart…

Dr. Maxine Greene was an American educational philosopher and educator who promoted the arts as a fundamental learning tool and in nearly 50 years at Teachers College, Columbia University. Greene was a prolific writer and lecturer on topics in education like multiculturalism and the power of imagination. Greene believed that creative thinking and robust imagining were not just the keys to an individual’s lifelong learning but to the flourishing of a demographic society (Weber, 2014). She believed that learning takes place when a learner takes responsibility and an active part in their own learning and she believed that democracy, social action, and social influence affected education and its outcomes.

Greene believed literacy empowers people. She recognized the importance of authentic speaking and writing – the kind that revels who a person is. She believed that fundamental skills learned in classroom are only a foundation, and learning cannot take place until learners can teach themselves (Greene, 1982). Greene argued that educators should not concentrate on learner competencies and believed that learners should not be reactive creatures or behaving organisms. She believed in aesthetic literacy or education, which assumes that the more a learner comes to know, the more they will come to see and hear. Each time a learner encounters a piece of art or literature, they should engage with it differently than the last time they encountered it based on new knowledge and lived situations they have acquired since their last encounter. Greene believed that art and literature provoked learners to pose questions and ponder their worlds (Greene, 1982).

According to Greene, the goal of an ideal curriculum is to provide a learner with an opportunity to make sense of the systems that shape and organize the world. She believed that when educating a learner, you are introducing that learner to a way of being and acting in the world that are new to his or her knowledge or experience. She believed both educators and learners need to be in a state of intense consciousness to focus on components of their curricular life-worlds in order to begin the process of learning (Zacharias, 2004). Greene believed in a progressive education philosophy. She believed educators should not only work as instructors in a classroom, but should empower the learner to search for meaning and not give them the meaning (Giarelli, 2006). Greene also believed in democratic pedagogy. She believed educators should encourage questions, critical thinking, and creativity. Greene believed in order to be authentic and effective the educator must be inquirer, discoverer, critic, and loved one. A true educator must come to class with all of the questions answered and subjects turned into an object ready to consume, but must come to class prepared to think critically, participate in discussions with students, defining the norms that governs their classroom, and allowing for possibly (Greene, 1982).

Greene believed that standard exams can’t quantify aesthetic engagement and learning is a transformative experience rather than a series of tasks that can be measured on a rubric (Gulla et al., 2020). She believed the primary outcome of education was to empower learners to think conceptually and to look through wider and more diverse perspectives in the world. She believed we owe learners the sight of open doors and open possibilities (Greene, 1982).

References

de Castell, S. & Luke, A. (1983). Models of literacy in North American schools: Social and historical conditions and consequences. In de Castell, Luke, and Egan (Eds) Literacy, Society, and Schooling. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Giarelli, J. M. (2016). Maxine Greene on Progressive Education: Toward a Public Philosophy of Education. Education and Culture, 32(1), 5–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.5703/educationculture.32.1.5.pdf

Greene, M. (1982). Literacy for What? The Phi Delta Kappan, 63(5), 326–329. https://maxinegreene.org/uploads/library/literacy_what.pdf

Gulla, A. N., Fairbank, H., & Noonan, S. M. (2020). IMAGINATION, INQUIRY, & VOICE: A Deweyan Approach to Education in a 21st Century Urban high School. Sense Publishers. https://www.lehman.edu/academics/education/middle-high-school-education/documents/ImaginationandInquiry-Gulla.pdf

Weber, B. (2014, June 5). Maxine Greene, 96, Dies; Education Theorist Saw Arts as Essential. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/05/nyregion/maxine-greene-teacher-and-educational-theorist-dies-at-96.html

Zacharias, M.E. (December 2004). Moving Beyond with Maxine Greene: Integrating Curriculum with Consciousness Educational Insights, 9(1). http://www.ccfi.educ.ubc.ca/publication/insights/v09n01/articles/zacharias.html