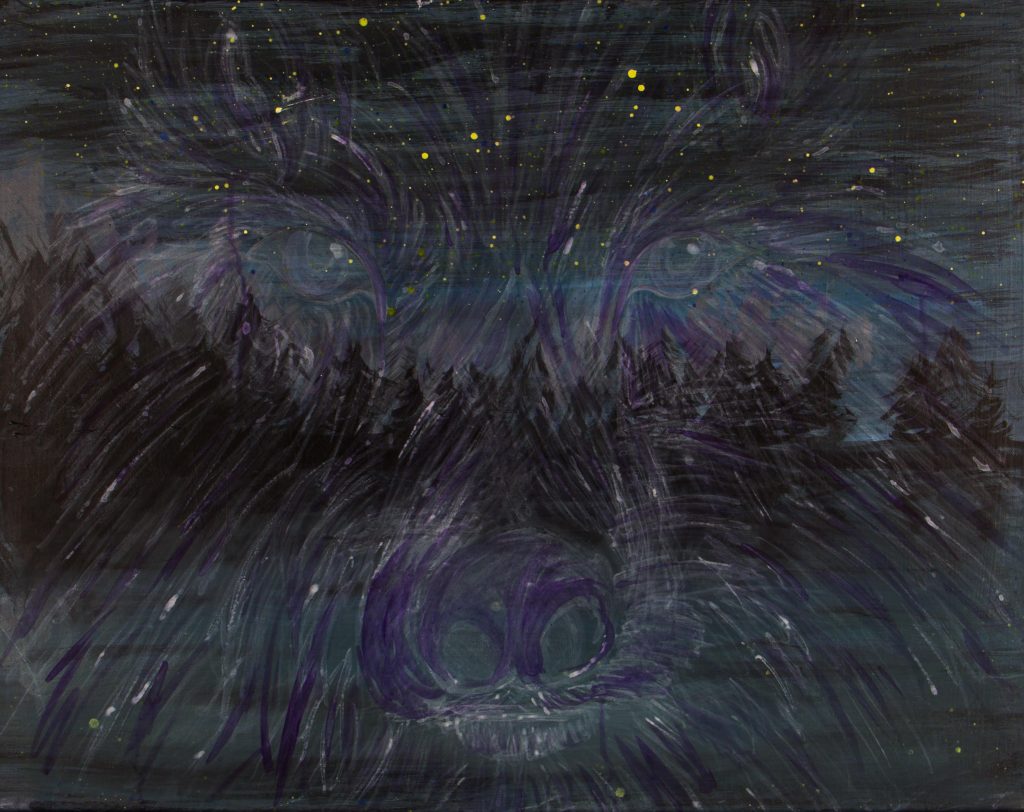

Coyote is a trickster – a “transformer, vagabond, imitator, prankstor, first creator, seducer, fool” (Robinson 8). Coyote is a being that is able to shift at will. Coyote is not bound by time – Coyote is everywhere, yet Coyote is nowhere.

In terms of First Peoples stories, Wendy Wickwire allows us a wonderful glimpse into the world of Coyote through both her introduction to Harry Robinson’s stories, and by transcribing them. Wickwire acknowledges that over the course of her interactions with various transcribed West Coast stories, Coyote was rarely mentioned. This is supported by John Lutz’s survey of stories, where Coyote is only mentioned within one (Paterson).

Yet, within the stories Robinson tells, Coyote is a central figure. So why is this?

Within the introduction to Robinson’s collection of stories, Wickwire wonders this same question: why is it that Robinson’s Coyote is so very different from the “quaint and timeless mythological accounts in the published collections” (10)?.

These previously published stories were short, edited, and “lifeless” (8), and “disrupted the integrity of the original narrative” (8). The transcribers had effectively “erased all sense of variation in the local storytelling tradition” (8).

They fit with “the pattern [of Levi-Strauss’ assigned zone]” (11); Robinson’s did not.

Within his book The Savage Mind, Claude Levi-Strauss details his theory regarding varying societies:

I have suggested elsewhere that the clumsy distinction between ‘peoples without history’ and others could with advantage be replaced by a distinction between what for convenience I called ‘cold’ and ‘hot’ societies: the former seeking, by the institutions they give themselves, to annul the possible effects of historical factors on their equilibrium and continuity in a quasi-automatic fashion; the latter resolutely internalizing the historical process and making it the moving power of their development (233-234)

As Wickwire summarizes: his view was that Indigenous – ‘cold’ societies’ -stories are static and timeless (10).

This theory, later criticised by Wickwire, is limited, lacking, and backwards.

However, this was a representation of the viewpoint at the time when many transcribers were aiming to “document some overarching, static, ideal type of culture, detached from its pragmatic and socially positioned moorings” (Robinson 22).

Wickwire theorizes, and I find myself agreeing with her, that prior documentation of stories were intentionally recorded outside of historical time, to fit more with the idea of the “romanticized, mythical Other” (Dion, “Braiding” 8); to fit more the framework of the “‘authentic’ mythological accounts” (Robinson 15) Western society associates with pre-contact societies. The voices, in a way were silenced; “limited to a single genre: the so-called ‘legends’, ‘folk tales’, and ‘myths’ set in prehistorical times” (22)

No longer timeless, Robinson brings coyote into the historical and away from the mythical; he places first peoples stories as just that – stories. He breaks away from the narrative of the “dead Indian” (Chamberlin) and we begin to see a culture full of meaning.

Wickwire writes that Robinson’s stories were more than their surface; “you can hear that again […] once or twice more” (Robinson, as quoted by Wickwire, 18). Robinson’s storytelling – stories of Coyote throughout history -was intentional, not an ‘anomaly’ from other published collections of tales. They “contained hidden messages and connections that would take time to decipher” (19).

Finding meaning, revisiting the deeper connotations of a story. This is what Robinson’s stories provide. Mythical stories provide deep meaning as well, but Robinson’s stories tell the human connection, which the others lack (Lutz, “Myth”).

As mentioned in lesson 2:2, the transcribers who were interpreting the Indigenous stories they encountered had their own motives (Paterson). These, we will never know, but it gives us a starting point for understanding why there is such a small example of Coyote within Lutz than Robinson: Coyote – the trickster and time-jumper – does not fit the narrative.

Works Cited

Chamberlin, J. Edward. “Eleven – Ceremonies”. If This Is Your Land,

Where Are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground. Kindle ed. Toronto:

Vintage Canada, 2004, loc. 2882 – 3193 of 3425.

Dion, Susan. Braiding Histories: Learning from Aboriginal Peoples

Experiences and Perspectives. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009.

Print.

Dion, Susan. “(Re)telling to Disrupt: Aboriginal People and Stories of

Canadian History”. Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum

Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2003, pp. 55-76.

King, Thomas. “Dead Indians: Too Heavy to Lift”. Hazlit. 30 November 2012.

https://hazlitt.net/feature/dead-indians-too-heavy-lift. Accessed on 21

February 2021.

Levi-Strauss, Claude. The Savage Mind, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson,

1966.

Lutz, John. “First Contact as Spiritual Performance”. Myth and Memory:

Rethinking Stories of Indigenous-European Contact, ed. Lutz,

University of British Columbia Press, 2007, pp. 30-45.

Lutz, John. “Myth Understandings: First Contact Over, and Over Again”.

Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indigenous-European Contact,

ed. Lutz, University of British Columbia Press, 2007, pp 1-15.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 2:2”. Canadian Literature, University of British

Columbia, February 2021. Lecture notes.

Robinson, Harry. “Introduction”. Living by Stories: a Journey of Landscape

and Memory, compiled and edited by Wendy Wickwire, Talon Books,

2005, pp. 1-30.

Hi Samantha,

First of all, I absolutely love your artwork!!

I also enjoyed reading your thoughts on why Coyote plays such a crucial role in Robinson’s stories. I think your conclusion that Robinson’s version of Coyote simply does not fit into the preconceived notions of Lutz’ narrative is very apt – it seems to me to relate directly to King’s experiences in New Zealand (Chapter II: You’re not the Indian I had in mind). The collected photographs were all carefully curated to create an image that fit what the creator had in mind – but did not necessarily reflect the whole truth. I find it a fascinating process, how we seem to gravitate towards the instinct to see exactly what we wish to see as opposed to looking deeper and discovering something unexpected. It reminds me of the positive confirmation bias – it is somehow more gratifying to have our suspicions confirmed, which just makes it all that much more important to recognize this instinct and work to counteract it! 🙂

Hello Magdalena, thank you!

I hadn’t considered the connection to King’s story – thank you for this! I would agree with you. Photographs – like stories, and even art – can be manipulated to the storyteller/artist’s point of view, and only show what said storyteller/artist WANTS the listener/reader/viewer to know.

Seeing what we wish to see is also a great way of looking at things from the listener/reader/viewer persepective. We are all making meaning based on what we know.

I think that your take away – that it is important to recognize our own limitations and how they influence us – is an important part of interacting with others stories. Like Robinson says to Warwick: “he stressed that they contained hidden messages and connections that would take time to decipher” (19). It is important we work to hear past our own experiences. Thank you for the comment!

Hi Samantha!

I enjoyed reading your post, and I think you’ve brought in a really great point about having to essentially “undo” toxic academic narratives brought in by anthropologists and researchers that had very limited understandings of the peoples or cultures they were studying. In the very limited anthropology courses I took, this was an on-going battle that current researches face, when their predecessors chose to study things that fit their preconceived narratives over objective study.

I had another thought too, when you were talking about the fact that cultural narratives are not stagnant. I think it’s very easy to get into the Westernized mindset of “set stories”. For example, if we think of a classic like Snow White, most of us are aware of the Disney narrative, and most are also aware of the Brother’s Grimm version as well. However, the Grimm brothers collected these tales from oral folktales told to them, and while you can find similar stories across various countries and cultures, they are all different, and this is due, I would argue, to the fact that they were told orally to begin with.

So I guess my question is, what are your thoughts on the malleable nature of oral narratives versus written ones. Do you think that oral tradition allows a story to continue to “live” and to be interacted with, both by the people and it’s environment? Or do you feel like there are ways for both forms of story telling to grow and change?

Hi Holly, thank you for your question(s)! I also thought of the early versions of traditional Western fairy tales while reading the course resources this week, and have though about this impact of orality. When studying ancient history in high school, we talked a lot about minstrels and travelling storytellers through the ‘dark ages’. I feel that oral stories have a bit more freedom to be altered based upon those who are interacting with them than written versions (there is something so permanent about the written word). Oral tales rely on memory and like Laura mentions in her blog post: “[f]irst stories are a complicated game of telephone, filled with misunderstanding and ambiguity from their origin and passed down through translations, through time”. I’m not sure I could have summed it up in a better way than her.

However, with the emergence of FanFiction, I wonder whether this notion/opinion I have will change. There is so much creative liberties that can be taken by storytellers, and seeing the different variations will be interesting.