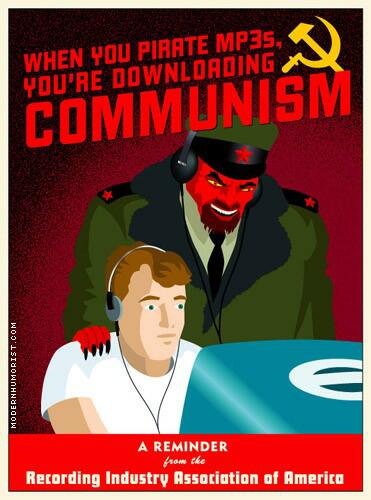

Image from modernhumorist.com

From Wired.com via RockRap.com:

File Sharing Lawsuits at a Crossroads, After 5 Years of RIAA Litigation

By David Kravets September 04, 2008 | 5:55:39 PM from wired.com

RIAA attorney Donald Verrilli Jr. says file sharers are automatically liable for copyright infringement and monetary damages for using peer-to-peer networks. Casey Lentz is trying to settle her RIAA lawsuit. She says the RIAA is “harassing” her.

It was five years ago Monday the Recording Industry Association of America began its massive litigation campaign that now includes more than 30,000 lawsuits targeting alleged copyright scofflaws on peer-to-peer networks.

The targets include the elderly, students, children and even the dead. No one in the U.S. who uses Kazaa, Limewire or other file sharing networks is immune from the RIAA’s investigators, and fines under the Copyright Act go up to $150,000 per purloined music track.

But despite the crackdown, billions of copies of copyrighted songs are now changing hands each year on file sharing services. All the while, some of the most fundamental legal questions surrounding the legality of file sharing have gone unanswered. Even the future of the RIAA’s only jury trial victory — against Minnesota mother Jammie Thomas — is in doubt. Some are wondering if the campaign has shaped up as an utter failure.

“We’re just barely scratching the surface of the legal issues,” says Ray Beckerman, a New York lawyer and one of the nation’s few who have taken an RIAA defendant’s case. “They’re extorting people — and for what purpose?”

When the first round of lawsuits were filed on Sept. 8, 2003 — targeting 261 defendants around the country — it was a hairpin turn from the RIAA’s previous strategy of going after services like Napster, RIAA president Cary Sherman said at the time. “It is simply to get peer-to-peer users to stop offering music that does not belong to them.” The goal in targeting music fans instead of businesses was “not to be vindictive or punitive,” says Sherman.

Today, the RIAA — the lobbying group for the world’s big four music companies, Sony BMG, Universal Music, EMI and Warner Music — admits that the lawsuits are largely a public relations effort, aimed at striking fear into the hearts of would-be downloaders. Spokeswoman Cara Duckworth of the RIAA says the lawsuits have spawned a “general sense of awareness” that file sharing copyrighted music without authorization is “illegal.”

“Think about what the legal marketplace and industry would look like today had we sat on our hands and done nothing,” Duckworth says in a statement. (The RIAA declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Casey Lentz, a 21-year-old former San Francisco State student, is among those caught in the RIAA’s PR campaign.

“They’re harassing me nonstop,” says Lentz, who’s been trying to settle her RIAA case, but can’t afford a lawyer. “I wasn’t the one who downloaded the music. It was a shared computer with my roommates and my friends. They want $7,500 for 10 songs.”

“I told them I only had $500 in my bank account. And they said ‘no way,'” she says.

Despite a fallow legal landscape, most defendants cannot afford attorneys and settle for a few thousand dollars rather than risk losing even more, Beckerman says. “There are still very few people fighting back as far as the litigation goes and they settle.”

“It costs more to hire a lawyer to defend these cases than take the settlement,” agrees Lory Lybeck, a Washington State attorney, who is leading a prospective class-action against the RIAA for engaging in what he says is “sham” litigation tactics. “That’s an important part of what’s going on. The recording industry is setting a price where you know they cannot hire lawyers. It’s a pretty well-designed system whereby people are not allowed any effective participation in one of the three prongs in the federal government.”

Settlement payments can be made on a website, where the funds are used to sue more defendants. None of the money is paid to artists.

The quick settlements have left largely unexamined some basic legal questions, such as the legality of the RIAA’s investigative tactics, and the question of what proof should be required to hold a defendant liable for peer-to-peer copyright infringement

In two cases, judges have ruled that making songs available on a peer-to-peer network does not constitute copyright infringement — the RIAA has to show that someone actually downloaded the material from a defendant’s open share folder. One of those cases is still mired in pretrial litigation. In the other, an Arizona judge issued a $40,000 judgment last week in favor of the recording industry, after learning the defendant tampered with his hard drive to conceal his downloading.

The so-called “making available” issue also emerged, belatedly, in the only RIAA file sharing lawsuit to go to trial: the case against Thomas, a Minnesota mother of three, who was slammed with a $222,000 judgment last year for sharing 24 tracks in her Kazaa folder.

Months after the Duluth, Minnesota jury’s October verdict, U.S. District Judge Michael Davis called the lawyers back to his courtroom. He said he likely committed a “manifest error” in the case by instructing (.pdf) the jury that merely offering music was infringement.

Judge Davis is expected any day to declare a mistrial in the case, and rule that the Copyright Act demands a showing of an actual “transfer” of files from Thomas’ share folder. If that line of reasoning is followed elsewhere, it endangers a key prong of the RIAA’s litigation strategy. The association believes it is technically impossible to prove that files offered on a peer-to-peer user’s shared folders were actually downloaded by anyone besides its own investigators. “It’s all done behind a veil,” RIAA attorney Donald Verrilli Jr. argued in the Thomas case last month.

That doesn’t mean the RIAA would be dead in the water. The recording industry could try to prove, through forensic examination, that the shared files were pirated to begin with, i.e., that the defendant infringed copyright law by downloading the music, before sharing it again. It’s also possible the courts will find that — as the RIAA has argued — downloads by the RIAA’s investigators can be considered infringement by the file sharer; digital rights advocates counter the recording industry should not be able to pay investigators to make downloads of its own music, and then declare them unauthorized copies.

The RIAA’s investigative tactics have come under attack as well. In a few states — Michigan, Texas, Florida, New York, Massachusetts, Oregon and Arizona — state governments and RIAA defendants have challenged the qualifications of the private company that develops the music industry’s cases.

MediaSentry — aka SafeNet — specializes in logging into peer-to-peer networks, where it downloads some music, takes screenshots of open share folders and documents the offending IP address. The RIAA’s position is that the online sleuthing isn’t covered by state laws regulating private investigators. But Michigan (.pdf) recently disagreed, and told MediaSentry it needed a private investigator’s license to continue practicing in that state.

Against that shifting legal backdrop, a handful of universities, including the University of Oregon, have begun refusing to divulge students’ names in file sharing lawsuits, on privacy grounds.

Nobody can credibly dispute that file sharing systems are a superhighway for pirated music. “There is no doubt that the volume of files on P2P is overwhelmingly infringing,” says Eric Garland, president of Los Angeles research firm BigChampagne. But critics of the RIAA say it’s time for the music industry to stop attacking fans, and start looking for alternatives. Fred von Lohmann, a staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, says the lawsuits are simply not reducing the number of people trading music online.

“If the goal is to reduce file sharing,” he says, “it’s a failure.”

www.rockrap.com

Follow

Follow