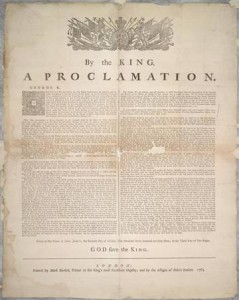

The Royal Proclamation 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was a document, issues by King George III, that dealt with the ‘ownership’ of North America. The Royal Proclamation was one of the first steps towards “the recognition of existing Aboriginal rights and title”. The Royal Proclamation has also been referred to as the “Indian Magna Carta”. The document was also issued in response to Pontiac’s War and the threat from the Thirteen Colonies and their desire for expansion.

The Royal Proclamation states, in summary, that Aboriginal title exists, and will continue to exist, until the land was ceded by treaty. The document made sure to outline that settlers could not claim land from Aboriginal occupants; instead land would have to be bought by the Crown and then sold to the settlers. By making sure to state that a treaty is required between the Crown/settlers and the Aboriginal people the document highlights that the land belongs to the Aboriginal peoples and that they need to be compensated for their land.

Although this document was a step in the right direction it was still written by the British without any input from the very people it was regarding thus, “clearly establishes a monopoly over Aboriginal lands by the British Crown”. (“Royal Proclamation, 1763.”). The documents guidelines highlighted that the Crown was a necessary agent for any land treaties or purchases – thus making the Crown indispensable (in the United States this document also held power, until the American Revolutionary War and subsequent independence) for land purchases and expansion. As well the Aboriginal nation could choose to sell their land or not – whether this practice was followed as closely as the law outlines is another matter.

At the end of the day this document did emphasize that the Crown was sovereign over the territory listed in the document, even though Aboriginal nations were given land rights and titles, the British Crown was emphasizing its power and sovereignty. Another issue arising from this document is a modern one – since the constitution still retains this proclamation it is technically valid till this day. However there is a problem with regards to the province of British Columbia: BC argues that since it did not exist when the document was issued it is not applicable to follow it. It is interesting to see how a document issued in 1763 can have such far reaching consequences, causing people to have ot prove their land rights and ownership.

While this document attempted to encourage the Aboriginal nations to accept British rule it is still a document written by and for the British Crown and, while being a step in the right direction with regards to Aboriginal rights, did serve to emphasize the sovereignty of the British Crown. Daniel Coleman’s argument about “White Civility” is poignant here because the document assumes that allowing a certain amount of rights would have encouraged Aboriginal people to give up their lands. As well the proclamation only encouraged British expansion and civilization in the region, only this time through more civil means like treaties. Since people today are forced to prove their land ownership – rather than the ownership being a given, without having to provide proof, as the document meant it to be, it is safe to say that this emphasizes the “fictive element of nation building” and that nationalism favors the British/white population rather than the whole Canadian population.

A quote from the Royal Proclamation extrapolates upon this idea:

“We do therefore, with the Advice of our Privy Council, declare it to be our Royal Will and Pleasure, that no Governor or Commander in Chief in any of our Colonies of Quebec, East Florida. or West Florida, do presume, upon any Pretence whatever, to grant Warrants of Survey, or pass any Patents for Lands beyond the Bounds of their respective Governments. as described in their Commissions: as also that no Governor or Commander in Chief in any of our other Colonies or Plantations in America do presume for the present, and until our further Pleasure be known, to grant Warrants of Survey, or pass Patents for any Lands beyond the Heads or Sources of any of the Rivers which fall into the Atlantic Ocean from the West and North West, or upon any Lands whatever, which, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us as aforesaid, are reserved to the said Indians, or any of them.” (“Royal Proclamation, 1763.”)

Works Cited

“Royal Proclamation, 1763.” Royal Proclamation, 1763. First Nations Studies Program, 2009. Web. 14 Aug. 2015.

Hall, Anthony J. “Royal Proclamation of 1763.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Ed. Gretchen Albers. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 02 July 2006. Web. 14 Aug. 2015.