Dear Readers,

This past week in ASTU we have been looking closely at Judith Butler’s Frames of War and today I will be focusing on a topic that stems from the reading: who do we mourn? Butler’s essay on precarity and the value of life emphasizes how some lives are mourned and others are not. We applied this reading to the novel, The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid, as well as the way in which the victims of 9/11 were mourned, but rather than expand on these applications, I would like to touch upon an issue that I was reminded of after reading Frames of War: gun violence in the United States.

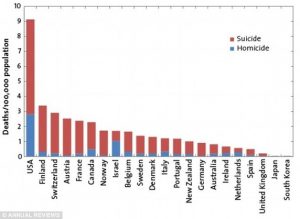

From age eight to eighteen, I spent the majority of my life living in Portland, Oregon, while two of those years were spent in Osaka, Japan. While living in the United States I remember doing in-school drills on how to respond to school shootings, and after I began habitually watching the news I distinctly recall the first time I saw coverage of a school shooting. Throughout middle to high school in America, I continued to read and see stories of gun violence and deaths from firearms on the news and twice my school district was alerted of a shooting threat on one of the local schools. As time passed I became, to my dismay, desensitized to news of gun violence and death as it had become such a consistent and almost normal aspect of living in the United States. This experience was greatly contrasted by the two years I spent living in Japan, where firearms are banned. Any singular event regarding firearms or drugs in Japan felt much more pronounced and carried more weight when presented on the news, and this has prompted me to consider how exposure to death and violence can alter the way one mourns, or who one mourns. Gun violence has been a longstanding and controversial issue in America, with constant debate surrounding the enforcement of gun control, however in many other countries (such as Japan and South Korea) gun control is strictly enforced or in some cases, like Switzerland, gun ownership is high but gun-related crime is relatively low, as shown by the attached chart depicting data on gun-related deaths collected by Annual Reviews.

To a certain extent, I believe it is important to consider how exposure to death and violence can influence who one mourns. As violence increases, for example in the case of school shootings, the loss of lives related to that act of violence can slowly be taken as a norm, and as one’s threshold for perceiving violence increases, it may take more serious acts to be considered as “mournable”. This is a dangerous consideration, as it brings to question one’s humanity and one’s ability to value the life of others during certain instances of death. It is undeniable that the United States has a complex history surrounding the culture of violence and the use of firearms, and I believe that the issue of gun violence must be addressed as it is cause for exposure to crime and violence to citizens that can slowly alter what are considered deaths worth mourning in the United States.