BTS is a K-Pop group that has been making waves in the West as “the biggest boy band in the world”. Debuted in 2013, BTS has been on a steady power crawl toward global stardom ever since, achieving numerous accolades and accomplishments in both hemispheres. As it relates to the West, and as a testament to this blog post, BTS won Artist of the Year at the 2021 American Music Awards after having swept several categories four years in a row. The release of their three English songs—“Dynamite”, “Butter”, and “Permission to Dance”—and their subsequent music videos in the past couple years have introduced for the group a potential migration toward a broader, more generalized Western audience. With the heavy presentation of Americana and other American iconography in their English-based music videos, BTS is perhaps further capitalizing off of their success by using these themes to appeal to a monolith of the West.

Before I move on to examples, I want to delineate Americana into two terms: music, and culture as a whole. This article describes Americana music as “a combination of several American genres: blues, gospel, country, bluegrass, and rock and roll”; beyond music, however, Americana includes “anything that’s representative of American culture” and is additionally quoted as possessing a nostalgic quality that “[romanticizes] the American dream.” Although BTS has collaborated with, and drawn inspiration from many American artists, for the purpose of this blog post I will only be focusing on the latter definition’s implication of material objects, rather than music.

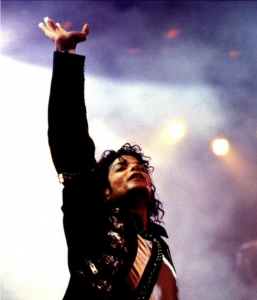

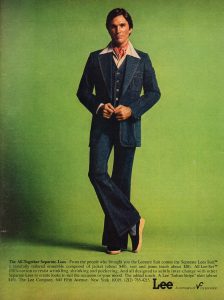

“Dynamite”, the first of their English releases, has influences from the 70s and 80s of American pop culture. From Michael Jackson to the classic teen coming-of-age movie, “Dynamite” features a very retro feel. The choreography of the video derives “several iconic poses and hook steps from the King of Pop”, with members dressed in 70s fashion. An included screen cap recalls the heavily poster-laden walls of Ferris Bueller’s room from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off , an 1986 American film starring Matthew Broderick. With nods to Route 66 and the prolific “Got Milk?” ads, “Dynamite” is packed with icons from America’s disco era and beyond.

BTS in “Dynamite”

BTS in “Dynamite”

Jungkook in “Dynamite”

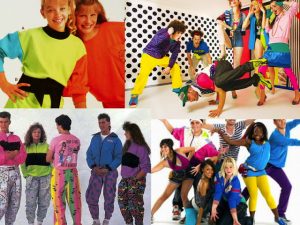

Sticking to the theme of throwbacks, “Butter” jumps another decade in time to 80s and 90s Hollywood. Although this music video is comparatively light-handed in pop culture references, there are strong allusions to the bright, neon colors and tracksuits that were a hallmark of fashion at the time. The design and costumes in “Butter” are reminiscent of movie sets, with film lights, “directors’” chairs, and even the trademark orange and teal color scheme prominent in many Hollywood movies. In line with movies, vocalist Kim Taehyung, also known by his stage name V, has cited Reservoir Dogs and Cry Baby as the inspiration for his slicked-back look, which was modeled particularly after Johnny Depp, because “’Butter’ felt like a teen musical to him.” Some of the best teen movies, or coming of age movies, include titles like The Breakfast Club, American Graffiti, and Sixteen Candles.

Suga in “Butter”

Jin in “Butter”

V in “Butter”

Arguably the most ostentatious out of the three in regards to fashion, “Permission to Dance” evokes familiar themes in the American Southwest. At its center is a diner, called a “cultural icon” by this article, as the setting of many films, novels, and other American works of art. Combined with the vast array of featured clothing like Cowboy hats and boots, fringe, embroidered paisley, chaps, and the debatable, yet extremely American, fashion faux pas of double denim, “Permission to Dance” embodies “the free spirit and rugged sense of adventure” possessed by the Hollywood cowboys, like John Voigt’s character in Midnight Cowboy, on which their costumes are based off of.

BTS in “Permission to Dance”

From left to right: Jungkook, J-Hope, Jin, Suga (front), V (back), RM, Jimin

V and Jungkook in “Permission to Dance”

BTS in “Permission to Dance”

When it comes to media, it’s important to remember that entertainment is an exportable product that is just as marketable as any other consumable good. In the wake of BTS’ international success, it only makes sense that they’d try to reach stages far flung from their native South Korea, and to engage with fans from all over the world. But as their popularity can attest to, there’s no need to appeal to audiences in the West—they already have. Rather, a “[celebration of] community on a wider scale”, that this article claims as the message of “Permission to Dance”, goes beyond English lyrics and Americana themes, which were of little consequence to long-time, dedicated fans. The diffusion, and distinction, of culture is one of the defining traits of BTS’ popularity: it is treated as something that should be embraced, instead of assimilated into the Western mainstream.