One of the things that interested me the most about Miller’s reading and the discussion in class was the idea of rhetorical situations and exigence. If genres respond and construct a rhetorical situation, than what does it say about a historical/social moment when a specific text or genre becomes wildly popular, and what were the conditions that gave rise to it in the first place? The quote I found in Miller that summed it up best for me was when she states: “studying the typical uses of rhetoric, and the forms that it takes in those uses, tells us less about the art of individual rhetors or the excellence of particular texts than it does about the character of a culture or a historical period” (Miller, 158).

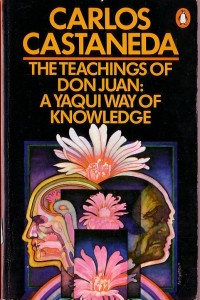

I like examples. I couldn’t help but think of the controversial anthropologist-turned cult leader Carlos Castaneda and his curious series of books recounting his apprenticeship with a Yaqui shaman during the 1960’s and 70’s. The books are written as a first person account of his doctoral thesis in anthropology at UCLA. They discuss shamanic practices, philosophy and cosmology, and the uses of psychotropic plants. Castaneda got his PhD, the books were universally praised, sold millions, and in many ways gave rise to the popular “New Age” genre in North America. They are also likely completely fake (here’s a good article discussing on Castaneda and his twisted cult of personality)

What is so fascinating about the books (I have only read the first 4) is how they blur the lines between genres; in this case academic anthropological study and autobiographical diary. Castaneda the academic recounts how he meets the subject of his study and struggles to record his beliefs. The first couple of books Castaneda speaks to us as a university student constantly doubting the worth and validity of his work. The first text even includes a structured analysis at the end of the first book, similar to what one would see in academic work. As the books progress we follow him as he immerses in the teachings, it becomes more and more difficult to differentiate between the so-called “true teachings” of the original anthropological subject of study, and Castaneda’s own beliefs. It was not until about ten years after the first book was published in 1968 that people started to question the validity of the accounts, citing confusing timelines in his narrative and other inconsistencies.

What was the rhetorical situation that led to such wide acclaim and seemingly lack of critical doubt, even in the publishing and academic world? For one thing the works fed into the 1960s counterculture’s exoticized fascination with Indigenous cultures, alternative spiritual discovery, and drug experimentation. In a sense the books were exactly what people wanted to hear. As for authorial motivation in the context of “interested texts,” I’d argue Castaneda saw an opportunity to become a literary sensation through the use of what was seen as a legitimate genre – in this case the autobiographical anthropological log – and jumped on it. Sociologist Richard De Mille unpacks the myth of Castaneda in rhetorical and cultural context in his excellent book Castaneda’s Journey: The Power and the Allegory. If these texts “work as a source of meaning” then they illuminate a desire by a certain part of society (I would venture to say mainly upper-middle-class white folks) who had become disenchanted with mainstream North American society and were searching for meaning through new and alternative belief structures. Its success lay in rhetoric “connecting the private with the public” (Miller, 163) in the sense of a deeply personal almost indescribable – and in the end fictional – spiritual journey within a larger public discourse. Increased fact-checking abilities through the Internet and our general suspicion of so-called “New Age” texts would definitely change our reception regarding a work like this were it published today.. I wonder what kind of texts would have the same kind of effect today as Castaneda’s did in the 60s.