One of the things that interested me the most about Miller’s reading and the discussion in class was the idea of rhetorical situations and exigence. If genres respond and construct a rhetorical situation, than what does it say about a historical/social moment when a specific text or genre becomes wildly popular, and what were the conditions that gave rise to it in the first place? The quote I found in Miller that summed it up best for me was when she states: “studying the typical uses of rhetoric, and the forms that it takes in those uses, tells us less about the art of individual rhetors or the excellence of particular texts than it does about the character of a culture or a historical period” (Miller, 158).

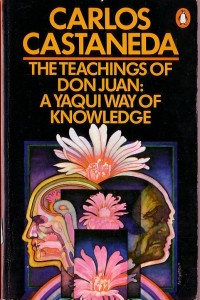

I like examples. I couldn’t help but think of the controversial anthropologist-turned cult leader Carlos Castaneda and his curious series of books recounting his apprenticeship with a Yaqui shaman during the 1960’s and 70’s. The books are written as a first person account of his doctoral thesis in anthropology at UCLA. They discuss shamanic practices, philosophy and cosmology, and the uses of psychotropic plants. Castaneda got his PhD, the books were universally praised, sold millions, and in many ways gave rise to the popular “New Age” genre in North America. They are also likely completely fake (here’s a good article discussing on Castaneda and his twisted cult of personality)

What is so fascinating about the books (I have only read the first 4) is how they blur the lines between genres; in this case academic anthropological study and autobiographical diary. Castaneda the academic recounts how he meets the subject of his study and struggles to record his beliefs. The first couple of books Castaneda speaks to us as a university student constantly doubting the worth and validity of his work. The first text even includes a structured analysis at the end of the first book, similar to what one would see in academic work. As the books progress we follow him as he immerses in the teachings, it becomes more and more difficult to differentiate between the so-called “true teachings” of the original anthropological subject of study, and Castaneda’s own beliefs. It was not until about ten years after the first book was published in 1968 that people started to question the validity of the accounts, citing confusing timelines in his narrative and other inconsistencies.

What was the rhetorical situation that led to such wide acclaim and seemingly lack of critical doubt, even in the publishing and academic world? For one thing the works fed into the 1960s counterculture’s exoticized fascination with Indigenous cultures, alternative spiritual discovery, and drug experimentation. In a sense the books were exactly what people wanted to hear. As for authorial motivation in the context of “interested texts,” I’d argue Castaneda saw an opportunity to become a literary sensation through the use of what was seen as a legitimate genre – in this case the autobiographical anthropological log – and jumped on it. Sociologist Richard De Mille unpacks the myth of Castaneda in rhetorical and cultural context in his excellent book Castaneda’s Journey: The Power and the Allegory. If these texts “work as a source of meaning” then they illuminate a desire by a certain part of society (I would venture to say mainly upper-middle-class white folks) who had become disenchanted with mainstream North American society and were searching for meaning through new and alternative belief structures. Its success lay in rhetoric “connecting the private with the public” (Miller, 163) in the sense of a deeply personal almost indescribable – and in the end fictional – spiritual journey within a larger public discourse. Increased fact-checking abilities through the Internet and our general suspicion of so-called “New Age” texts would definitely change our reception regarding a work like this were it published today.. I wonder what kind of texts would have the same kind of effect today as Castaneda’s did in the 60s.

Sam!

Your discussion here reminded me of Alan Sokal’s hoax during the science wars, a series of exchanges in the 90s broadly between scientists and post-modernists, that trolled (would that be too anachronistic to say?) a prominent cultural studies journal into accepting completely bogus work.

I’ll link skeptic’s dictionary perspective on the hoax (http://www.skepdic.com/sokal.html) because it summarizes Sokal’s intentions fairly well. It’s interesting to see that New Age rhetoric still has a fairly strong hold on consumers of journals like Social Text in the 1990s. I would argue that this hold hasn’t necessarily waned today either, especially because digital filter bubbles serve to consolidate people’s biases.

When rhetorical genres, as Miller insists, have to do with meanings rather than facts, I can’t help but wonder about the distinctions that leftists continue to make between post-structuralists and scientists/positivists, and why such distinctions are made at all by academic and activist leftists. One example I think should be noted is the recent spat between Chomsky and Žižek. Actually, I should say that I deliberately chose not to follow any of the spat, because I intuited that the issue was about celebrity, not their ideas. They knew that such a rivalry would garner attention, and milked every second of it.

It’s almost as though these two white male philosophers wanted to reify the conflict that continued throughout the 90s, to insist that their ideas and leadership are still relevant. It’s as though they wanted to capitalize on society’s obsession with celebrity and garner attention to the tension they create in the left.

For someone like me, who also chose not to follow any of the feminist twitter wars, the very idea of celebrity should be questioned. As soon as the intended humility of a name like “bell hooks” loses its humility to the public, that is, as soon as bell hooks, Chomsky, or local thinkers and rabble-rousers are seen as icons instead of a collection of ideas and strategies we can use, we fuel the exigence for celebrity and soften the potential for impactful social change.

The importance of celebrity in our culture is definitely seen in our obsession with memoir, which give us an impression of having intimacy with the “I” in question, to give us a sense that we have an “in” on that life. We all want to be celebrities, and to be friends with celebrities, and that’s why corporate personalization sites such as Facebook and Tumblr are so powerful.

Sorry that I’ve written a tad much! I have a lot of feelings about these issues. 🙂

– Jane Shi

Interesting insights here, thanks for the great comment Jane! I had not heard about the Sokal incident before you mentioned it, what a fantastic example of trickery and social commentary at the same time. What a great example of digital filter bubbles (as a consequence of the proliferation of Internet Age information) simply solidifying our beliefs. I still believe people are more questioning about where they get there information in the Internet Age, but I would think this is more of a social phenomena than a deliberate, conscientious effort in Jacques Rancere’s sense of “aesthetic revolutions”(QUESTION EVERYTHING).

Maybe I was wrong about our renewed ability to fact-check…Your example also highlights how maybe we need to become even more questioning of where our information is coming from, since we are now so flooded with it and so-called “news sources” keep popping up every day it seems. The viral nature of info sharing online seems also to be very dangerous (think of the KONY fiasco). Are we entering a new era of Yellow Journalism? Sorry I think I kinda got off topic..

Celebrity! I know very little about the spat between Zizek and Chomsky. I think fundamentally it was a ideological disagreement, but Chomsky has always been critical of the psychoanalytical school of Lacan, Zizek, etc. When it comes to celebrity or caring about it, I’d have to assume (but this is pure bias and speculation fuelled by speculative media as most media is) that Zizek cares more about celebrity then Chomsky… While I think that it is silly to argue that one approach is “better” than the other (I think it’s super important to have both traditions of thought) I can understand Chomsky’s concern regarding how Zizek’s ideas are taken by society. What do you think? Is it possible that the psychoanalytic approach to ideology – the way Zizek discusses it through references to contemporary pop culture (media, movies, celebrities, etc.) lends itself particularly well to being corrupted by the mainstream media and become fuel for the corporate celebrity industrial complex of our time? Surely it is important for us to analyze this, and he can do it in the layman’s terms, like his Perverts Guide series on film and ideology. We can’t solely blame the author for how their ideas are received once it has been put to ink, or digital ink. But still, like what does it mean for Zizek to be interviewed by Salon, Vice, Vanity Fair, etc? How does the medium affect the message.

I don’t know if what I’ve written makes any sense haha, but yeah, it’s such a fascinating issue!