La Patum: resistència sota l’opressió en 1960s Espanya franquista

The collective memory of the West in the 1960s invokes images of the protests in Prague and Paris with American hippies dictating the fashion and lifestyle. However, in Francoist Spain, a much quieter resistance was taking place. Spain has occupied Catalonia since 1714 and from 1939 to 1975, Francisco Franco’s dictatorship aimed to destroy Catalan culture in hopes to create a homogeneous Spain. All over Catalonia, the development of a modern Catalan society challenged the Franco regime and increased common awareness of the Catalan oppressed state[1]. The focus of this paper will be on the small northern Catalonian town of Berga, and their actions in the years immediately after Franco’s visit to the region. Berga is home to La Patum, a multi-day festival to celebrate Corpus Christi made up of numerous performances from salts [characters]. This festival dates back to the medieval times and today is the basis of Berga’s tourism and blatant displays of catalanitat [Catalan-ess] (for a fuller description, please see the endnotes[i]). In the 1960s, under Franco, the Patum took on new symbolism as it separated itself from its Catholic roots and embraced unspokenly and secretly, the national ideals and anti-Regime rhetoric which were gaining momentum throughout Catalonia. Through this, the search for an authentic self and women’s role were renegotiated through the body. Occurring at the same time as the outspoken, public and sometimes unpredictable, student protests of the spring 1968, La Patum of the late sixties operated much more subtly and calculated under colonization as it was used as a space to challenge the authority and explore the self.

Spanish Oppression

Franco’s Spain was to be Catholic, united and Spanish – in language and culture. His visit to Berga on July 1 1966 illustrates these intentions. During his visit he was greeted by signs and an archway [pictured] proclaiming “Franco! Berga is with you!” and “Peace and progress”[2]. Nine-teen sixty-six marked 27 years since the Spanish civil war, (a war Franco started), in 1939 left Berga (and all of Catalonia) with deep scars. Under Franco, all Catalan culture was outlawed (with La Patum being a curious exception) with exile, execution or imprisonment as possible punishments for acts such as speaking Catalan or dancing the sardana[3]. To proclaim that Berga was ‘with’ Franco, was Catalans accepting their role as an ‘other’ and their colonized status[4].

The Vangaurdia Española (based in Barcelona, the Catalonia capital), grandiosely dedicated the first seven pages of their July 2 1966 edition to Franco’s visit. The paper placed a photograph of the crowded Sant Pere Plaça as the headliner image with the caption “the town of Berga, [tipped into] the street [to] acclaim Franco”[6]. The verb, volcar, used here as “tipped into” has several translations, most of them negative and translate along the lines of “to upset” or “to irritate”. This subtle verb choice may be telling of the (lack of) agency of the crowd despite their cheerful exterior. Several pages later in the same seven page spread, the article states that Franco was met with great cheer which “closed any hint of divisive maneuvers that seeks to disrupt the peace of Spain”[7]. This rather blunt sentence hints to either previous dissent in Berga, or to the growing threat of dissent in Catalonia during this time period. Franco knew that Spain needed Catalonia and in order perpetuate faux-unity, there had to be some concessions to the Catalans.

To appeal to the masses which were in the streets, Franco addressed the Catalan crowd and spoke of the importance of “our” Patum, especially the l’Águila [eagle], was a symbol of their “moral values, for [Catalonian] unwavering and steadfast commitment to the national spirit. […] love of country, […] Spain”[8]. In one speech, Franco cemented La Patum and l’Áglia to Spain and the Catholic Church. Spain further claimed La Patum as their own when in 1967 the ministry of Information and Tourism (the Francoist propagandists) declared La Patum to be important to “national interests”[9]. Removing the catalanitat from the uniquely Catalan festival, and by claiming the region (and resources[10]) as Spain’s, Franco solidified his rule over Catalonia.

Regional Resistance

Franco’s visit to Berga happened near the height of the 1962 to 1967 period of social awareness of the Catalonian cultural oppression. Unlike their European peers, the student movement was not a key factor in this awakening. It may have played a role, as there were student movements in Barcelona however, they were quickly silenced by infighting or the regime[11]. Barcelonian life is not equivocal to Bergdiuan. Berga is geographically isolated with an older, God-fearing, demographic. Therefore, Berga challenged Franco’s narrative within the contexts and institutions Franco permitted and in a form the city could agree with. La Patum, the Church and the body became sites of peaceful and accepted resistance to the Franco regime and Spain.

The Berguedàn Church, as an institution, had a large role in embracing Catalan culture under Franco, especially in the late 1960s. Mossèn Josep Armengou i Feliu[12], a Berguedàn priest was very interested in Catalan society and culture and wanted to ensure its survival. Holding secret Catalan classes for the middle class children and delivering sermons which were filled with “veiled political allusion”, he was arguably the most ‘outspoken’ Berguedàn at the time[13]. He published the first scholarly approach and interpretation of La Patum in 1968. As mentioned previously, the Catalan language was outlawed under Franco, for Mn. Armengou to not only teach it, preach about it, but publish an account of La Patum that, in his view and argument, was “national death and resurrection” was extraordinary[14].

The nation here (in “national death”), refers to Catalonia, a repossession from Franco’s claim that La Patum belonged to the Church and to Spain. The Catalan church by 1969 had completely separated itself from the Franco regime over labour union disputes and by 1970, the Catholic church of Berga withdrew the Catholic procession portion of La Patum[15]. That was the last official tie between the Church and La Patum, a separation which had been in the works since the mid 1960s[16]. This separation allowed the salts and the festival in the Plaça Sant Pere to grow in popularity and become increasingly important to the creation of a Catalonia nation, and not to the Church which was enmeshed with the State.

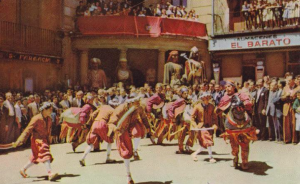

With the religious aspects toned down and Catalan culture embraced, the Patums of the late 1960s were the celebration of a “people that defends and loves their customs” wrote the same article which announced La Patum’s status as a “national interest”[17]. The Patum of 1967 will be filled with “joy and enthusiasm” continued the article. The Patums’ of years previous were not written with such pride, it is possible to suggest that Franco’s visit in 1966 and the January 1967 decision to include it as a national interest (even if as a Spanish one), sparked a fire of pride in what they had. One father wrote into the Vangaurdia in 1968 and spoke of how La Patum was “growing [Catalan] culture” in Berga and especially in children[18]. The Patum was visibly growing catalanitat through the use of Catalan imagery, mainly colours. On a postcard, it shows els turcs i els cavallers and the male gegants dressed in red and yellow stripped clothing. The thinner strips on the gegants specifically suggest that they are an homage to the (banned) Catalan flag, while at the same time being passable as the Spanish flag’s colours.

the Plaça Sant Pere and the Berga town hall.[19]

“[…] an imprisoned princess who embroiders with hope the banner of her liberation, all at once it begins to pull, uncontainable, from side to side, until, its chains broken, it takes broad flight for the serene sky of liberty”[20].

Mn. Armengou’s Àguila is the silent and peaceful Catalan fighter who is slowly breaking free from her chains, from both the State and the Church, and is preparing to fly into a future independent Catalan state. However, the popular rumour is that the finale to l’Àguila’s dance (when she spins over the crouched audience) once “killed a solider” so while she is peaceful, she is deadly[21]. This served as a firm warning to Franco and the State that claimed de facto ownership of her. This symbolism is derived from the same dance Franco saw, a dance which he derived a loyal love of the State. Just like the Catalan flag outfits, the new interpretation of the l’ Àguila, could be argued to be pro-Spanish and Regime if questioned.

Personal expression and the search for the authentic

La Patum was not just a subtle nationalistic act, it was a deeply personal. One could not simply watch La Patum, as being in the Plaça Sant Pere is being part of La Patum[22]. Mn. Armengou described the experience in religious terms as a “baptism of ritual fire which confers upon him who feels it the most authentic certificate of Berguedàn citizenship”[23]. The embrace of Patum’s “authentic[ness]” or “pure[ness]”[24], is important not only to the physical event, the unique salts and dances, but to the participants and their internalization of catalanitat and exploration of self.

In the same spirit La Patum employed resistance to a colonizing force in a much more subdued manner when compared to their Western equivalents, the Berguedàn sexual revolution of the 1960s can not hold a candle to the popular image of communes and “free love”. Berga was not an ideal space for a sexual revolution in the 1960s, the small town mentality and strong church influence thwarted efforts of a sexualized liberation. That was not to say they did not try. Dorothy Noyes author of Fire in The Plaça spoke to participants of late sixties Patums who remarked on the gendered participation and sexual harassment. In the past, when the lights dimmed in the plaça to prepare for the plens, the women were expected to leave. (It is also important to note that there were not that many women in the audience if you the postcard’s demographics as representative). One patumarie[25] recalled “all the men in the plaça clustered around” the women who stayed and “when the lights went out, ui!”[26]. In the throws of the chaos of the plens, in the dark and the blinding light of firecrackers, the women expected groping[27]. One patumarie sheepishly told Noyes that the reason she stayed in the plaça for the plens was because “there’s always some shameless fellow who gooses you”[28]. However, slowly more and more women stayed in the plaça. In this regard, the the experience of La Patum for women in the 1960s was similar to women in other global movements – excluded from participating at an equal level and being at the whim of male gaze.

Instead of sexually, the body was employed to experience a sort of freedom that was new to the young Berguedàns. The younger Berguedàns were born under the Franco regime and the Church, La Patum was the “first occasion of freedom from family” and their watchful eyes[29]. Within the same space sexuality was explored, the plens also served as a space for a beugardian “happening”. To outsiders, plens are a curious display of fire and chaos, but to those inside, it is putting catalanitat into performance[30]. The plens are a uniquely Bergaduan folk figure, watching them is an undeniably “authentic” Bergidan experience, let alone, a Catalan one[31]. The plens increased in number from sixteen in the 1950s to forty in the late 1960s[32]. This increase made the experience of the plens more intense but also allowed more patumaires to participate[33] in La Patum. This participation was a contribution to the ever growing catalanitat present in La Patum and in the hearts and minds of the patumaries.

The embrace and reinterpretation of La Patum on multiple levels (the State, the region and individual) in the late 1960s served many purposes. For Franco, in his attempt to “unify” Spain and colonize Catalonia, he claimed La Patum (with l’Àguila) and Berguedàns for a pro-united-Spain narrative. The same symbolism Franco saw, the Church and Berguedàns then used to their anti-Regime and pro-Catalan rhetoric, while still appearing to support the Regime. Using the Church as a front, Mn. Armengou fostered a sense of catalanitat in the patumaries who in then in turn used La Patum to explore sexuality and their own sense of growing national pride despite Church and Regime opposition.

Secondary sources:

Balcells, Albert. Catalan Nationalism: Past and Present. Translated by Jacqueline Hall. New York: Springer, 1995.

Noyes, Dorothy. Fire in the Plaça: Catalan Festival Politics after Franco. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2003.

Primary sources:

Armengou i Feliu, Josep. La Patum de Berga: Compilacio de dades historiques, amb un suplement musical dels ballets de La Patum. Berga: Columna/Albí, 1968. Cited in Dorothy Noyes, Fire in the Plaça: Catalan Festival Politics after Franco. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2003.

Aquí Bergudeá. “La visita de Franco a Berga l’any 66 – “Apoteosis en Berga””. Filmed July 1 1966. YouTube video, 3:55. Posted November 14, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQW0o5hJSzI.

“Berga: Las fiestas de “La Patum” declaradas de interés turístico.” La Vanguardia Española, March 30, 1969. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1967/01/15/LVG19670115-034.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016). [Berga: The festival of “La Patum” declared a touristic interest.]

“Exposiciones de pintura en Berga.” La Vanguardia Española, September 21, 1968. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1968/09/21/LVG19680921-020.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016). [Painting exhibitions in Berga.]

“Gran importancia de la Cuenca carbonifera de Berga.” La Vanguardia Española, July 1, 1966. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1966/07/01/LVG19660701-008.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016). [Great importance of the Bergan coalfields.]

“Inenarrable recibimiento a Francisco Franco en Berga y Santa Maria de Queralt.” La Vanguardia Española, July 2, 1966. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1966/07/02/LVG19660702-001.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016). [Inexpressible welcome to Francisco Franco in Berga and Santa Maria of Queralt.]

Petachrome de la Passola. La Patum: Els Turcs i Cavallers. Prior to Jan 4 1968. Serie II Núm. 602, Berga.

“Vibrantes y entusiasta recibimientos populares en Berga y Manresa.” La Vanguardia Española, July 2, 1966. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1966/07/02/LVG19660702-005.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016). [Vibrant and enthusiastic receptions popular in Berga and Manresa.]

[1] Albert Balcells, Catalan Nationalism: Past and Present. Trans. Jacqueline Hall (New York: Springer, 1995), 157.

[2] Aquí Bergudeá. “La visita de Franco a Berga l’any 66 – “Apoteosis en Berga””. Filmed July 1 1966. YouTube video, 3:55. Posted November 14, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQW0o5hJSzI.

[3] A traditional folk dance, where the dancers dance in a circle.

[4] Dorothy Noyes, Fire in the Plaça: Catalan Festival Politics after Franco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2003), 165.

[5] Aquí Bergudeá. “La visita de Franco a Berga l’any 66 – “Apoteosis en Berga””. Filmed July 1 1966. YouTube video, Posted November 14, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQW0o5hJSzI, 0:24.

[6] “Inenarrable recibimiento a Francisco Franco en Berga y Santa Maria de Queralt.” La Vanguardia Española, July 2, 1966. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1966/07/02/LVG19660702-001.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016).

[7] “Vibrantes y entusiasta recibimientos populares en Berga y Manresa.” La Vanguardia Española, July 2, 1966. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1966/07/02/LVG19660702-005.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016).

[8] “Our city, we can not deny is small for the number of its inhabitants, but great for its traditions, for their moral values, for their unwavering and steadfast commitment to the national spirit, highlighted throughout its history. The eagle there, engraved on the back of the crest, a copy of which appears in our traditional celebration par excellence, La Patum, is the symbol, respected by all future generations of Berga, that love of country, heightened today by the providential circumstance [formal] you are the governing destinations in Spain and imbue our people an era of prosperity and security ever achieved by previous rulers.”; “Berga y Manresa.” La Vanguardia Española, July 2, 1966.

[9] “Berga: Las fiestas de “La Patum” declaradas de interés turístico.” La Vanguardia Española, January 15 1967. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1967/01/15/LVG19670115-034.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016).

[10] Franco’s emphasis on peace and cooperation from Catalans was vital because he was also relying on the coal reserves near Berga for exploitation for Spain. On the day of his visit, the Vanguardia Española ran a thirty-page insert about the region’s coal mines. These were appeals to the Berguedàn (and generally Catalan) working class. The newspaper insert stressed the importance and celebrated “our” (Spain’s and Catalonia’s) coal mines as they would “solve the social and economic problems of the nation”. The Berga coal mines were producing 31% of the nation’s (Spain and Catalonia’s) coal in 1960.; “Gran importancia de la Cuenca carbonifera de Berga.” La Vanguardia Española, July 1, 1966. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1966/07/01/LVG19660701-008.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016).

[11] Balcells, Catalan Nationalism, 158.

[12] Catalan naming traditions gives the child both the father’s and the mother’s family names, in everyday use, the father’s family name is used. Mossèn, shorted to Mn., is the Catalan equivalent to the use of Rev. for Reverend.

[13] Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 176.

[14] Ibid., 179.

[15] Balcells, Catalan Nationalism,163.; Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 176.

[16] Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 176.

[17] “interés turístico,” La Vanguardia Española, January 15 1967.

[18] “Exposiciones de pintura en Berga.” La Vanguardia Española, September 21, 1968. http://hemeroteca-paginas.lavanguardia.com/LVE07/HEM/1968/09/21/LVG19680921-020.pdf (accessed March 20, 2016).

[19] Petachrome de la Passola. La Patum: Els Turcs i Cavallers. Prior to Jan 4 1968. Serie II Núm. 602, Berga.

[20] Josep Armengou i Feliu, La Patum de Berga: Compilacio de dades historiques, amb un suplement musical dels ballets de La Patum (Berga: Columna/Albí, 1968), 87. Cited in Dorothy Noyes, Fire in the Plaça: Catalan Festival Politics after Franco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2003), 180.

[21] It is a common saying/story told during La Patum. Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 180.

[22] Armengou, La Patum de Berga, 18. Cited in Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 184.

[23] Armengou, La Patum de Berga, 125. Cited in Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 177.

[24] “interés turístico,” La Vanguardia Española, January 15 1967.

[25] Patumarie translates to “one who does Patum”. In other words, is someone who participates in Patum.

[26] Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 187.

[27] Something that was told to me when I was “learning the ropes” of La Patum. I was also strongly encouraged to not stay in the plaça during the plens and to not walk in the area surrounding the Plaça Sant Pere alone. This gendered division and sexual harassment is a persistent problem. So much that La Patum in 2015 hung posters which translated to “no means no”.

[28] Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 187.

[29] Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 186.

[30] Ibid., 184.

[31] Armengou, La Patum de Berga, 50. Cited in Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 181.

[32] Armengou, La Patum de Berga, 100. Cited in Noyes, Fire in the Plaça, 184.

[33] It is possible to argue that there is no audience in La Patum, as the audience are also participants as they dance with the music and salts, but for simplicity, I have divided those in the plaça into a ‘audience’ who watches and ‘participants’ who are characters in the salts.

[i] “The Patum takes place every year during the week of Corpus Christi, between the end of May and the end of June, and comprises several parts: […] the full Patum. The Taba (tambourine), the Turks, Cavallets (papier mâché horses), Maces (demons wielding maces and whips), Guites (mule dragons), the eagle, giant-headed dwarves, Plens (fire demons) and giants dressed as Saracens are all allegorical figures and representations that parade one after the other through the streets, performing different acrobatic tricks and spreading light and music among the joyous audience. All the figures join to perform the final dance, the Tirabol.”

UNESCO. “The Patum of Berga.” Third Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Accessed March 20 2016. http://www.unesco.org/culture/intangible-heritage/38eur_uk.htm.

[5]

[5]

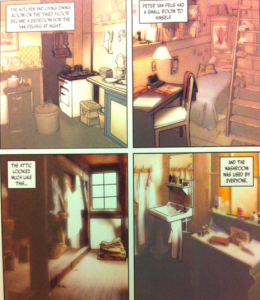

In this example (page 74 of Anne Frank), Jacobson and Colón drew the Annex in a realistic style. In doing this not only are they able to set the scene of where the Frank family lived, but to (as I’ll describe later one) convey to the reader that this is/was a real space occupied by the Frank family during their daily lives and limits the universality which could arise from simply describing the rooms.

In this example (page 74 of Anne Frank), Jacobson and Colón drew the Annex in a realistic style. In doing this not only are they able to set the scene of where the Frank family lived, but to (as I’ll describe later one) convey to the reader that this is/was a real space occupied by the Frank family during their daily lives and limits the universality which could arise from simply describing the rooms.