Anne Frank: Using Graphic Novels to Teach and Connect New Readers to the Holocaust

(This paper was presented at the Thompson Rivers University Undergraduate History, Philosophy and Politics conference in January 2016.)

The Diary of Anne Frank propelled Anne’s name and image across the world. Her bestselling diary and an extremely popular museum dedicated to her have elevated Anne to the status of being the face of the Nazi genocide. From this honour, it is not a question of if or why Anne Frank is used in teaching, instead it is a matter of how. To effectively teach Anne Frank in the classroom, the issues surrounding the diary in the context of the classroom need to be addressed. Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón worked closely with the Anne Frank House to create Anne Frank: Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography, a graphic novel adaptation of Anne’s original diary. In this graphic novel, the narrative picks up where The Diary of Anne Frank left off and allows new younger audiences to connect with Anne Frank’s life. Through their work, Jacobson and Colón tackle many problems inadvertently created by the diary. Their use of creative license and the graphic novel format to create an accessible and clearer narrative while removing the possibility of backlash from controversial moments. At the same time, they do not shy away from showing the growing severity and the harsh reality of the Frank family in Nazi-occupied Netherlands. To make up for what is lost in the transition from diary to graphic novel, Jacobson and Colón rely on art as a vehicle for emotion, and to portray the events in the original diary. Anne Frank has come to symbolize the Holocaust to many and the graphic novel Anne Frank by Jacobson and Colón attempts to connect young readers to Frank’s life and as an introduction to the Holocaust by tastefully trying to “complete” The Diary of Anne Frank. With every work stemming from The Diary of Anne Frank being created with an audience in mind, it is my argument that the Anne Frank graphic biography was created in attempt to “complete” The Diary of Anne Frank for readers – younger readers in particular. “Completing” The Diary of Anne Frank, is multifaceted and my argument will focus on the mediation’s accessibility, appealing to today’s attitudes, filling out historical details, and the additional dimensions visuals add to Anne’s story. Due to its nature as being a mediation from the original, it is unjust to critique the relationship between the two. Instead I will be using this area to explore the way the Anne Frank graphic biography was able to communicate Anne Frank’s legacy to larger, modern, audiences.

The annex which is the main setting of Anne’s diary is now known as the “Anne Frank House”, a museum space dedicated to preserving and spreading the memory of Anne Frank and “her ideals” [1]. Founded by Otto Frank after the war, the museum officially opened May 3 1960. Today, the museum welcomes reportedly one million visitors a year, making it one of the three most popular museums in Amsterdam, according to its website. The museum’s success is intrinsically linked to The Diary of Anne Frank’s world-wide success. The Diary of Anne Frank has an influence reached by few other books by being “translated into scores of languages, published in hundreds of editions, printed in tens of millions of copies, and ranked as one of the most widely read books on the planet.” [2] There is no surprise that Anne Frank has been transformed into the primary character in Holocaust studies, particularly for children and young adults.

This diary (and house) has earned Anne Frank the privileged spot of being the representation of the Holocaust to a sizable majority of people. Her diary is hallmarked as being the quintessential “innocent child victim” however, her diary and story is a very atypical story of the Holocaust. It is important to note that any survivor’s story in and of itself is a “miracle” story, the fact that the Frank family were able to hide for two years and evade death is a miracle of miracles. The archetypal story of the Holocaust to millions of Jews was deportation and murder. If they were able to be recorded into popular memory, it was by being in a mass of faceless and nameless individuals. The fact that Anne has been able to exist in collective memory not only as a name, but also as a face is something extraordinary.

Holocaust education exemplifies those who survived and were able to publish their memoirs, with Anne Frank being the most popular account. According to Sara Horowitz, the key factor in using these accounts to effectively teach is to leave the students with an understanding that is greater than believing Anne Frank and her story is “what the Holocaust [was] about”[3]. The Diary of Anne Frank is only the story of seven individuals out of an estimated four and a half million victims of the Nazi Regime. Anne’s diary and the story she preserved for future readers can not speak for every victim of the holocaust. An alternative to using traditional methods of teaching Anne Frank with The Diary of Anne Frank, has been to embrace the growing popularity of graphic novels. With the wide scope of topics covered by graphic novels and the immensely popular works such as Art Speigalman’s Maus series, graphic novels have been able to separate themselves from being labeled “comic books”[4]. Their appeal to students allow educators to introduce “literature that they might otherwise never encounter”[5].

The importance I am placing on teaching and particularly young adults and children is that this generation, born roughly 1990 to the present, will be the generation that will see the last survivors of the camps pass away, leaving only memoirs to tell first hand accounts[6]. This attention and sense of urgency in preservation has brought many adaptations to Anne’s legacy and countless other works take inspiration from Anne’s story, memory and identity. Every new mediation creates something related to the original, but is a new independent work. A mediation in this context are, the works which act in effort to reconcile the relationship between the reader and original. In this case, a mediation of Anne Frank is any creation that is derived from her story, memory and/or identity that works to connect the reader to Anne in a creation that is not The Diary of Anne Frank[7]. Each mediation, with each new work, creates new relationships, be it between the new work and the source, or between the new work and the new work’s audience. The mediation is not intended to be an area for critique and criticism, instead, it is a space where meaning can be added and expressed[8]. Prior to his death in 1980, Otto Frank and the Anne Frank-Fond (the organization founded founded in memory of Anne) tightly regulated what could and could not bear his late daughter’s name. Even after his death, the Anne Frank House remained the authoritative voice although with less strict regulation[9].

This is why I have chosen to use and focus on Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón’s 2010 graphic novel Anne Frank: Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography and its contribution to the teaching of Anne Frank and broader, the Holocaust, while using the graphic novel format and being approved by the Anne Frank House. The graphic biography written by Jacobson and drawn by Colón, was a project initiated by the Anne Frank House in 2008. Jacobson and Colón each have extensive resumes in comic books and spent two years labouring over the narrative of Anne Frank to create their 2010 publication with utmost accuracy.[10] In Anne Frank Jacobson and Colón continue this quality of work while maintaining the original “honesty, tone and contents” of The Diary of Anne Frank[11].

Jacobson and Colón compressed the entire history of Anne Frank and her family from the diary’s roughly two to three hundred pages (varies amongst editions) into 152 pages of full colour illustrations. This change allows the Anne Frank graphic biography to continue the Anne Frank House’s mission of bringing Anne’s story “to as large an audience as possible” adding that they wanted to include those who were perhaps not ready, or old enough to read and fully comprehend the intricacies of the original[12]. Despite this, the graphic novel is not over-simplified for child readers and does not shy away from the magnitude of the Holocaust, but simply is working within the constrictions of the medium[13]. The nature of a graphic novel requires information to be sacrificed due to space issues and the need to balance text and visuals. That said, the graphic novel of Anne Frank has been written for those not prepared or perhaps unable to comprehend the sometimes convoluted stories Anne Frank left.

To address the concerns of the difficult original, including passages that are hard to imagine, Jacobson and Colón use the graphic novel medium and a bit of artistic license to their advantage. They rearranged the way in which Anne told the story of her family. Starting Anne Frank before Edith and Otto Frank met, Jacobson and Colón allow the reader to connect with Anne’s parents independently from what Anne chose to tell the reader in the later portions of her diary. In the diary, she explains her family history sporadically and nearly as an afterthought starting one diary entry of May 8 1944 with “Dear Kitty, Have I ever really told you anything about our family?”[14]. Jacobson and Colón extract all the family history plus some additional details to form the “prologue” to the Annex and the keeping of the diary.

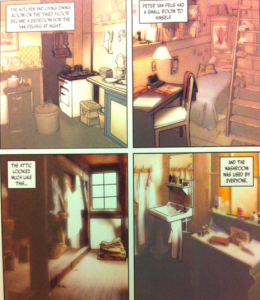

Additionally, being a visual based medium, the graphic novel allowed for maps and visualizations of places and events that are difficult to comprehend solely from reading The Diary of Anne Frank. Most notable is the cut away diagram of the Annex and the drawings of individual rooms on pages 51 and 74 respectively (and to a lesser extent page 72). These highly detailed panels employ an artistic technique which limit the “universality” of the setting[15]. By using highly detailed panels, Colón limits the spaces which can be described in Anne’s description of the rooms to being unmistakably the Annex. The Anne Frank graphic novel attempts to reconcile problems unavoidable in pieces of literature and text based mediums by limiting the vast array of what readers could imagine by, quite literally, painting a picture. By reorganizing and illustrating difficult ideas, Jacobson and Colón make Anne Frank’s story accessible to a wider audience, namely those previously alienated by the original text.

In this example (page 74 of Anne Frank), Jacobson and Colón drew the Annex in a realistic style. In doing this not only are they able to set the scene of where the Frank family lived, but to (as I’ll describe later one) convey to the reader that this is/was a real space occupied by the Frank family during their daily lives and limits the universality which could arise from simply describing the rooms.

In this example (page 74 of Anne Frank), Jacobson and Colón drew the Annex in a realistic style. In doing this not only are they able to set the scene of where the Frank family lived, but to (as I’ll describe later one) convey to the reader that this is/was a real space occupied by the Frank family during their daily lives and limits the universality which could arise from simply describing the rooms.

Also note the still bright, yet distinctly burnt orange tones Colón used to set the mood of the Annex (which I will also describe in greater detail later).

In this mediation Jacobson and Colón not only address a new audience, but a new generation of readers with differing sensibilities. The mainstream audience did not receive The Diary of Anne Frank without controversy. Most of this controversy is regarding Anne’s exploration of sexuality, her body and becoming a woman. Passages such as January 5 and 7 1944 which Anne spoke openly and frankly about sex, her curiosity about the female body, and desires to kiss her female friend, are the just a few sites of this controversy. All of which are noticeably absent from Jacobson and Colón’s rendition because in order to be used in an education setting, the materials must be “appropriate” for adolescents[16]. These passages do however appear in The Definitive Edition of Anne’s diary that was published after Otto Frank’s death. When Otto was preparing for the first edition of The Diary of Anne Frank to be published, he removed several passages either to respect the memory of his late wife Edith whom Anne often spoke harshly of, or to keep the memory of Anne modest. It is possible Jacobson and Colón removed these passages to stay in keeping with Otto’s wishes despite the Definitive Edition being widely available in English since at least 1995[17]. However, the more probable answer is that these passages were left out to avoid repercussions and allow classrooms to be able to use the graphic novel without much concern from parents.

There are only two hints of sexuality and becoming a woman that remain present in the graphic novel. The kiss between Peter and Anne occurs on page 109 without much extravagance. Also briefly mentioned is Anne beginning menstruation on page 91. The changes presented in Anne Frank are centered on her changing attitudes of women’s place in the home and society[18]. While those changes also played a part in The Diary of Anne Frank, the physical and emotional changes which were written with immense detail and care by Anne are reduced to be small points in Anne Frank. Jacobson and Colón are perhaps aware of the modern sensibilities of readers and wrote their graphic novel to avoid possible controversies like the original text experienced. By leaving in small hints that allude to the curiosity and changes Anne experienced regarding sexuality, womanhood and her own body, they find balance in the fine line between the narrative of The Diary of Anne Frank and appealing to modern (parental) sensibility.

Also significant is what Jacobson and Colón decide to expand upon in Anne Frank. Many, including Lawrence Langer, a professor of Holocaust education, call The Diary of Anne Frank a “soft version of the Nazi genocide” and leave the reader with a sense of “optimism” due to the lack of a “view of the apocalypse”[19]. Langer does not feel The Diary Of Anne Frank captures the enormity of Holocaust, a feeling that is confirmed when students report being more concerned about Anne’s personal issues, than “why she was in the attic”[20]. To address this concern, Jacobson and Colón illustrate and incorporate two important features into Anne Frank. The first is their use of juxtaposition in panels contrasting public and private domains and the second is the inclusion of the Frank women’s final months.

The ability to juxtapose the public and private life is thanks to the ability of the graphic novel to display multiple storylines at once, which is not possible in text based works. These appear as either single panels, or page “snapshots” of key historical events. The best example of this is seen on page 15 of Anne Frank. On this page there is baby Anne being welcomed to the world by her maternal grandmother, while on the opposite page, Adolf Hitler is being welcomed to a Nazi Party rally in Nuremburg. The Frank family continues to live their private lives in the domestic sphere, while slowly the events of Europe begin to impact every aspect of their lives. By constantly reminding the reader of the greater context, Jacobson and Colón hope the readers comprehend the remote and disturbing history and attempt to understand why the Franks were in the annex and the severity of their situation, instead of solely focusing on the immediate problems of Anne[21].

Secondly, the continuation of the graphic novel beyond the arrest of the Annex diminishes the optimism and ambiguity of the afterword’s ending of The Diary of Anne Frank. By explicitly showing what happened to Anne and Margot after the arrest, Jacobson and Colón attempt to show the “common” story of the Holocaust. To do this, they follow the Frank family from their arrest, to the transport camp of Westerbork. From Westerbork, they were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and separated. After Otto and Edith were separated from Anne and Margot, the panels focus on the sisters’ battles with starvation, disease and the cold until both Anne and Margot passed away[22].

As well, this stark reality addresses concerns that the abrupt ending of the diary offers too much “optimism” about Anne’s time in concentration camps. This “optimism” was observed when teachers noted that students avoided knowing the events after the arrest, instead wanting to focus on how Anne may have enjoyed the sunshine and fresh air in the camps[23]. Jacobson and Colón wanted to take advantage of writing in hindsight and filling in historical gaps Anne had not included in her original diary. Their inclusion of the constant reminders of outside forces acting upon the Frank, and every other family like them, solidified the severity of the situation and in addition the expanded narrative of what happened post-arrest allows little room for unwarranted optimism.

The long, emotional prose of The Diary of Anne Frank can not be reproduced in its entirety but Colón used the graphic novel’s medium to his advantage to convey emotion to the reader. First, he imagined and visually expressed Anne’s emotions allowing the reader to “read” her face to gain insight into her emotions. Due to the high degree of accuracy in portraying Anne’s emotions, it’s possible to gain a fuller understanding of the situation as well[24]. Using real family photographs taken by Otto, Colón was able to recreate Anne in different poses and ages as well as recreating entire memories. Memories such as Anne’s tenth birthday on page 47 is a stylistic rendering of the actual photograph. As “seeing is believing,” through reinforcing real memories, with real photographs, the reader connects with the real, everyday life of Anne[25]. The graphic novel is unique from its closely related, yet vastly different mediums of literature or film, yet vastly different in that it allows a reader to linger on either singular panels or entire pages. Having highly detailed panels draws the eye to linger, and hopefully reflect on the why the image was chosen. Using the idea of universality again, the highly realistic illustrations Colón implements do not allow for the reader to see anyone other than Anne and her family. This does not allow Anne and her story to be lost within the larger narrative of the Holocaust. As well, because Colón draws characters highly detailed and as unique beings, they are unmistakably the one person they are to represent. This ensures Anne Frank’s story stays connect with Anne Frank and is not seen as an interchangeable “universal” story.

Artistic choices in colour also help connect the reader to Anne’s life and draw the eye. The panels depicting the Franks’ various homes are brightly coloured with lots of emphasis on greens and yellows. Even in the Annex, the colours are still bright, but are now more of an olive green and burnt orange. When the graphic novel moves into the camps, the colours change to brown, gray and a dull purple[26]. The colours set the tone of the environment and mood. Despite the lack of space for a text based work, the graphic novel opens up new avenues to carry and display visual emotional cues for the reader such as integrating “real” objects into the panels and utilizing colours to influence mood. The “themes” of colour depending on the setting and mood, shows over-arching story emotions and that would be difficult to constantly have within a narrative text without being repetitive. Reality works with this idea of “background” emotion functioning together with “foreground” emotion, as does the graphic novel. An example of this on page 127, is when despite being surrounded by the grays and dull purples which signify Auschwitz-Birkenau, the reader sees Anne and Margot smiling and celebrating Hanukkah. The entire mood of an environment (such as Auschwitz-Birkenau’s “mood” of horror and death) can exist with the “foreground” emotions of small moments of happiness.

Due to Anne’s status as the shining example of Jewishness in the Holocaust, her diary has made her immortal within the context of the Holocaust education. With the millions of visitors to the Annex every year in Amsterdam and countless more readers, it is not surprising that to many, Anne is the face and basis of understanding of the holocaust. Jacobson and Colón work with the current and most popular method to teach Anne’s life, The Diary of Anne Frank and translate it into a beautiful, accessible graphic novel aimed for teaching not only about Anne and the Frank family, but about Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. It’s no longer a question of if we should teach Anne Frank as an introduction to the Holocaust, but how and Jacobson and Colón’s work captures the emotion, the story, and the life of the young girl while being aware of the original’s downfalls to modern readers. By omitting subject matter previously considered controversial, as well as expanding and exploring the historical context, Jacobson and Colón create a classroom friendly version of Anne Frank for future generations to continue to bear witness to the atrocities of the Holocaust.

Bibliography:

Abramovitch, Ilana. “Teaching Anne Frank in the United States.” In Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory, edited by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler, 160-179. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Anne Frank Foundation, “Anne Frank House: Organisation.” http://www.annefrank.org/en/Sitewide/Organisation/ (accessed November 9, 2015).

Bucher, Katherine T., and M. Lee Manning. “Bringing Graphic Novels into a School’s Curriculum.” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 78 (2004): 67-72.

Frank, Anne. The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition. Translated by Arnold J. Pomerans and B.M. Mooyaart-Doubleday. New York: Doubleday, 1989.

Horowitz, Sara R. “The Literary Afterlives of Anne Frank.” In Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory, edited by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler, 215-253. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Jacobson, Sid, and Ernie Colón. Anne Frank: Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Kitchen Sink Press, 1993.

Tabachnick, Stephen E. “The Holocaust Graphic Novel.” In The Quest for Jewish Belief and Identity in the Graphic Novel, by Stephen Tabachnick, 39-81. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2014.

[1] Anne Frank Foundation, “Anne Frank House: Organization,” http://www.annefrank.org/en/Sitewide/Organisation/ (accessed November 9, 2015).

[2] Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler, “Introduction,” In Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory, ed. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 1.

[3] Sara R Horowitz, “The Literary Afterlives of Anne Frank,” In Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory, ed. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 218.

[4] Katherine T. Bucher, and M. Lee Manning, “Bringing Graphic Novels into a School’s Curriculum,” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 56 (2004): 68.

[5] Bucher and Manning, “Bringing Graphic Novels,” 68.

[6] Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Shandler, Introduction, 21.

[7] Arguably, even The Diary of Anne Frank is a mediation, as the true original is not published and was edited by others after her death. For the sake of simplifying my argument, I will regard the The Diary of Anne Frank as Anne Frank’s original work and not as a mediation.

[8] Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Shandler, Introduction, 7.

[9] Ibid., 11.

[10] Stephen E Tabachnick, “The Holocaust Graphic Novel,” In The Quest for Jewish Belief and Identity in the Graphic Novel, by Stephen Tabachnick (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2014), 52.

[11] Tabachnick, The Holocaust Graphic Novel, 51.

[12] Ilana Abramovitch, “Teaching Anne Frank in the United States,” In Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory, ed. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 172.

[13] Tabachnick, The Holocaust Graphic Novel, 53.

[14]Anne Frank, The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition, Trans. Arnold J. Pomerans and B.M. Mooyaart-Doubleday (New York: Doubleday, 1989), 636.

[15] Scott McCloud, “Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art” (New York: Kitchen Sink Press, 1993), 31.

[16] Bucher and Manning, “Bringing Graphic Novels,” 69. However, it is important to note that “appropriate” is of course, subjective. In the school system, I think it is fair to assume that conservative values, especially those rooted in Christian beliefs, are the “standard”.

[17] Abramovitch, Teaching Anne Frank, 174.

[18] Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón, Anne Frank: Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 110.

[19] Horowitz, The Literary Afterlives, 217., Abramovitch, Teaching Anne Frank, 165.

[20] Abramovitch, Teaching Anne Frank, 165.

[21] Abramovitch, Teaching Anne Frank, 168.

[22] Jacobson, Anne Frank, 116-130.

[23] Abramovitch, Teaching Anne Frank, 167-8.

[24] Tabachnick, The Holocaust Graphic Novel, 56.

[25] Ibid., 56.

[26] For best examples of these see Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón, Anne Frank, Apartment 17, Annex 102-103, Camp 120-121.