In my early conversations with professional educators, I have learnt that self-assessment is an important aspect of teaching. Through a conversation with a professor, I came to understand that learning to effectively assess myself as a teacher will be a particularly important given that after my practicum I will rarely be assessed by anyone else unless problems arise. Another professor helped realize that if I am not mindful of my areas of weakness my choices for professional development may centre more so on my personal interests and have little relevance for improving my practice. This may be particularly tempting with professional development options such as the all-day fitness and golf workshops available at a recent PHE conference. Therefore, I will need to take responsibility for assessing myself so that I can be intentional about my professional growth.

In a conversation with a vice principal, I learnt that student assessment is a common way teachers assess themselves. If the students are doing well, then the teacher is doing a good job. This seems to be in line with John Wooden’s notion that “you haven’t taught until they have learned” (Turley, S., 2008). However, I think that student assessment reveals only a general understanding of a teacher’s effectiveness. If student assessments reveal that many students are struggling, this indicates that the teacher needs to improve, but gives minimal insights into their specific areas needing improvement. The students could be struggling for many reasons pertaining to the teacher’s practice; the teacher could be failing to engage or motivate the student; the content could be too advanced; the assessments could be unfair and so on. Therefore, I think teacher self-assessment needs to move beyond student assessment.

Only one secondary school teacher that I spoke with regularly used teacher self-assessment rubrics in their practice. For this independent school educator, the rubric is used as part of a school-wide annual process. Each teacher fills out the rubric and reviews it with the vice principal as part of their performance review. This rubric was quite similar to others I found online and in other educational resources. I found the self-assessment rubrics, particularly the topics and questions, helpful for understanding the key aspects of teaching for which I, as a teacher, should be mindful.

However, the rubrics seemed to be a bit disconnect from the teaching experience. The topics and questions felt too general and far removed from the instructional time and setting. While doing the self-assessment the teacher must think back over their past actions after time has passed. In addition, as a secondary school teacher with two teachable subjects, I found it difficult to answer the questions because my answers might vary depending on if I was in a gym or classroom setting. For example, in light of feedback from my faculty advisor, I know my voice projection in the classroom is strong; but through my PHE Micro-teaching experiences, I learnt that I struggle with voice projection in the gymnasium and on the field. None of the rubrics took in to account that teachers strengths could vary in different settings. Through observations and conversations with my school advisor, I learnt that a teacher’s performance may vary even when teaching the same subject and grade level to two different classes, pending on the class dynamics or even the time of day that they have each class. No rubrics took this factors into account, which I think would make them less useful for gaining specific insights into one’s day to day teaching practice. This lead me to investigate other methods for teacher self-assessment, particularly self-reflection which seems to address the issues I have with rubrics.

My further academic readings revealed how reflection can be used as a powerful tool for self-assessment and in turn professional growth when understood and conducted with respect to the notion of a ‘reflective practice.’ Reflective practice is a process by which practitioners grow in their professional knowledge through on-going critical examination of one’s own actions so as to engage in continuous learning through their experiences (Schön, 2008). Here reflection is “a product, not a process” (MacKinnon, Clarke et Erickson, p. 93, 2013). Reflection is not an abstract thing one does, like ‘navel-gazing’; rather reflection is what is gained, such as tangible constructive insights or plans for improving one’s performance.

Reflective practice involves two fundamental processes: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (Capel, Breckon & O’Neil, 2006). Reflection-in-action is an instantaneous assessment of one’s own behaviour as it happens. It is “intuitive knowing” of one’s performance with regards to one’s “knowledge-in-practice” (Schön, p. 276, 1991). It can be understood as ‘thinking on your feet.’ This involves making choices in the moment concerning one’s course of action based on observation skills such as reading the class (Capel, Breckon & O’Neil, 2006). On the contrary, reflection-on-action is “systematic and deliberate thinking back over one’s actions” to better understand what happened and why (Capel et. Al., 2006, p.19). A teacher assessing if they met the intended objectives of a lesson or unit is a prime example of reflection-on-action. Through both reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action, practitioners discern ways to address issues and improve professionally.

Donald Schön’s conception of the reflective practice emphasizes problem setting as opposed to problem-solving. Problem setting recognizes that each problem is unique and intrinsically connected to the setting in which it arises. Schön “frames his conceptualization of reflective practice in terms of the immediacy of the action setting” (Clarke, p. 245, 1995). Problem setting is the process in which “we name the things to which we attend and frame the context in which we will attend to them” (Schön, p. 40, 1991). The reflective practice requires practitioners to be in a continual conversation with their practice environments.

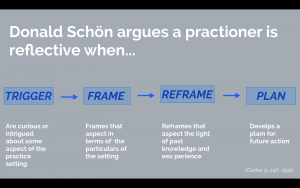

Donald Schön’s conception of the reflective practice involves four steps: trigger, frame, reframe and plan. A practitioner is professionally reflective when they progress through each step and in reference to their setting. Reflection begins when a ‘trigger’ that causes the practitioner to be curious or intrigued by an aspect of the practice setting. After which they ‘frame’ that aspect in terms of the particulars of their setting. Then they ‘reframe’ that aspect with reference to their past knowledge or previous experience. Lastly, they develop a plan for future action. (Clarke, p. 246, 1995). Through a spiralling process of “framing and reframing” the practitioner comes “to new understandings of situations and new possibilities for action” (Clarke, p. 245, 1995). Hens, the reflective process is like cyclical and ongoing like a helix. After a plan is implemented in the practice setting, it prompts new triggers, which extends the reflective process. As the practitioner frame, reframe and plan they bring the insight gained from their previous spirals of inquiry.

Molly E. Romano’s article, Teacher reflections on ‘bumpy moments’ in teaching: a self-study, gave me a clear example of teacher reflection for self-assessment. Romano’s 25-day self-study is a prime example of reflection-on-action. Romano’s self-study involved videotaping her teaching days, and then reviewing and analyzing the tapes each night for what she described as “bumpy moments” (Romano, 2004, p. 666). Through this process of taping and reflecting she identified the causes for her bumpy moments, most of which she found fell into four main categories. Romano’s article serves as an example for me of how intentional engagement the reflective process can reveal patterns in one’s practice, which can later serve to guide future choices for professional development opportunities.