Screen sovereignty to me means power, voice, and strength. In terms of Indigenous new media, I view this as challenging norms and showcasing Indigenous work from Indigenous peoples on and off screen to prove they are not assimilated and won’t stop standing up for their rights. What this looks like is inevitable and is up to the producers themselves, which is why screen sovereignty is so unique, fun, and unpredictable. For example, A Tribe Called Red’s ‘ALie’ video shown in class on Oct 24 was a moving and powerful piece that forces viewers to rethink city landscapes. Ever since the Oka “Crisis”, Indigenous media has changed forever (Dowell, 12), provoking a lot of change in the last 26 years.

According to Dowell, visual sovereignty is defined as the articulation of Aboriginal peoples’ distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through aesthetic and cinematic means (2).” She is referring to this as an act of self-determination and pride in Indigenous identity that is driven by current and past political policies that continue to be assimilative and undermining. There has been an increasing # of on and off screen movements that continue to trump misrepresentations of Aboriginal peoples.This drive represents the “distinctive political status that derives from Aboriginal peoples’ ties to lands prior to colonization (1-2).” The power of media can infect viewers opinions about anything, particularly those of marginalized groups, so Aboriginal films are crucial in that there is a fully complete representation of individuals/communities.

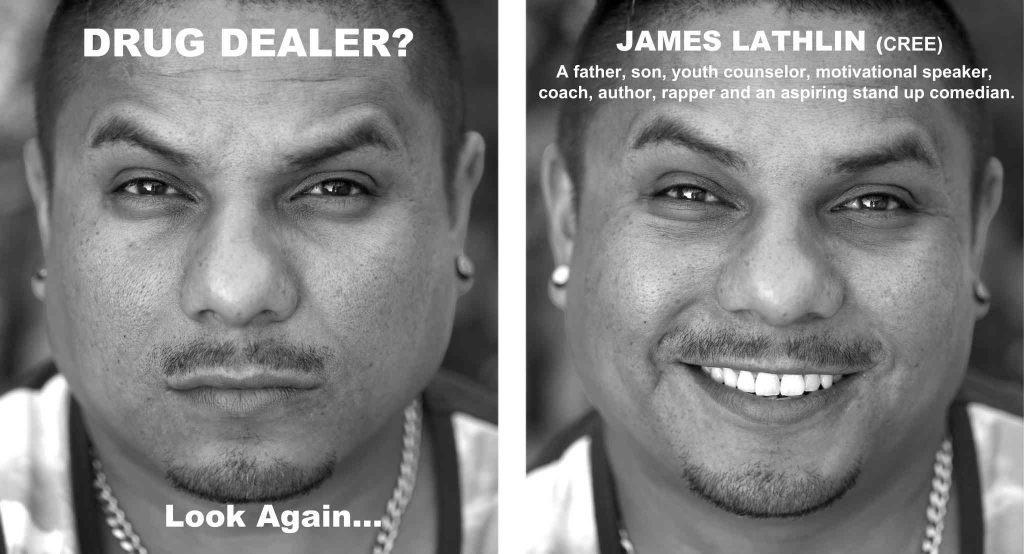

Tackling the “R” word exhibit by KC Adams challenges negative portrayals of Indigenous people. This was sparked after Tina Fontaine’s body was found in the Red River.

A strong example is God’s Lake Narrows by Kevin Lee Burton, an interactive multilayered website that allows viewers to get a first-hand look at what life on a reserve is like. The site is what Dowell would refer to as “reclaiming the screen to tell Aboriginal stories from Aboriginal perspectives (2).” This is shown in Burton’s work through stories from people’s homes on a reserve located in God’s Lake Narrows, a very remote and small community that is 2,037 km’s from Vancouver. He challenges stereotypes of reserves by letting viewers into his community and allowing people to listen to conversations that occur, which shifts from haunting to warming/humourous as one progress through the site. Dowell states that this “writes Aboriginal presence on the land (14)”, which represents Aboriginal voices (realistically) through collaboration, teamwork, and community involvement by an Aboriginal filmmaker. Talk about reserves is often heard on social media and the news – mostly negative and depressing, particularly up north – which may be true to an extent, but it’s typically written through the lens of someone who is not from the community; therefore, their perspective(s) may be misleading and adding to racist .

If it weren’t for this website, I believe most people would have think of the area as just as non-existent or just a hot fishing destination that is like “heaven”, as presented on www.godslake.com or other overtly racist preconceptions and judgements. This piece tackles that by presenting the cold blunt truth, which is what is needed in order for audiences to be educated. Someone needs to address these issues if the government won’t… When it comes to reserves, there is a lack of coverage. Many First Nations and/or reserves are unheard about nationwide unless something ‘big’ (usually negative) happens (i.e.: Attawapiskat suicide crisis), otherwise, no one seems to know about their existence, which is exactly what the government intended/s to do. Although it has worked to a certain extent, it’s also being constantly challenged by Aboriginal peoples through the power of technology to prove they’re not invisible or dead communities. It’s a continuous and ongoing journey… #decolonization

I will focus on a few distinctions that stood out for me and explain why I believe this piece is impactful as a non-Indigenous viewer: 1) Community collaboration, 2) Audio, 3) Visuals.

- Community: As mentioned in Dowell, Aboriginal families have and are continuing to connect and bandage up some of the problems caused by colonization through media production (3). This is an example of screen sovereignty because it allows new relationships to be made, old ones to be strengthened/repaired, and can spark movements or even new ideas within and out of the community. It sometimes creates a domino effect that inspires others to take action and challenge mainstream media, such as #IdleNoMore, which has continuously received a massive amount of support or the Dakota Pipeline Protest that has gained widespread media coverage and is supported by many non-Indigenous people such as Chris Hemsworth. As someone from the outside who has been on a reserve, I think it’s important to look at this with an open mind and recognize the presence of Aboriginal peoples around the territory you are situated on. In the end, it can be a life changing journey for some to heal and move forward because it is decolonial and positive. The drive that forms sovereignty represents the “distinctive political status that derives from Aboriginal peoples’ ties to lands prior to colonization (Dowell, 1-2).”

- Audio: voice is one of the most powerful aspects in technology. It can often be more impactful than images. In an industry that has been mainly white-dominated, this piece paints over that and we get to listen to real voices of community members. This is screen sovereignty because their stories are being expressed through their stories and lens – what goes in the final production is made by them, so this gives a true voice to God’s Lake. This relates to Dowell’s statement about Aboriginal filmmakers reversing power dynamics to the right for self-representation (5) and showing audiences alternative perspectives of land/city scapes. It not only features quiet, almost depressing sounds in the beginning, but also brings out the good in a small community. I can personally relate to this as I who grew up in a small town – there is always a unique/special tie to our territories.

- Visuals: this site geotags where you are and tells you how far away the closest reserve is. This can be a reminder of whose territory you sit on (Dowell, 6) no matter where you are. This is screen sovereignty because can unsettle and challenge a viewer’s perspective in the sense that it forces people to think about their location/home and get a sense of what life is like on the reserve. Although it doesn’t feature everything people see on reserves. With the power of media, a place that is extremely inaccessible is made accessible through cyberspace, but still intimate and personal. For example, an exhibit by Urban Shaman featured images from Burton, called RESERVE(d). It shows that even in bad conditions, people can make good out of a dreadful place.[1] Aboriginal media has resulted in what Dowell calls “a web of people that gives you strength (13)” as screen sovereignty is constantly moving forward on and off screen. This is also a a new way to educate people through non-traditional means.

[1] http://www.thompsoncitizen.net/news/nickel-belt/winnipeg-art-exhibit-features-photos-from-gods-lake-narrows-1.1366163