In the final chapter of If this is your land, Where are your stories? There were many more than three interesting topics that stuck with me, but the the most interesting metaphor used by Chamberlain, is that of table manners. In the first chapter, he tells us a story of watching an old Ukrainian woman eat peas with a knife, and upon replication, he is chastised by his parents for his poor table manners. “Learn to speak Ukrainian and you can eat peas with a knife” (Chamberlain 9) This metaphor is reused in the final chapter of the book, and explains its relevance by likening table manners to the concepts of subjective truth, the importance of commonality through ceremony, and the use of title as an excuse for societal dominance.

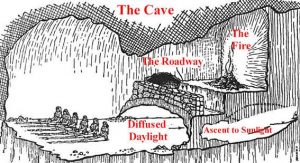

Subjective truth is a wonderfully profound concept. What is truth? Why is what I believe any or less valid than what someone else believes? Plato tell us “the allegory of the cave” to help us define the path to truth. The most interesting point that Chamberlain makes “contradictory truths can be troubling” (Chamberlain 221) and as uncomfortable as the thought makes us it will allow us to establish a dialog when we realize that both sides must work together to find common truth. We can find common truth by connecting with each other with the same wonder of a man who has exited the cave for the first time. We must leave our caves (what we have been told is true) in order to see truth. The only way to leave our cave is to explore and ask for assistance from people who have left the cave, (or a person with experience different from our own.

On page 220 of If this is your land, Where are your stories? Chamberlain tell us a story of the Gitksan people’s oral legend of a landslide. This story involved the displeasure of the gods and a heard of running grizzly bears creating a landslide which buried the people of Temlaxum, a village at the base of the sacred mountain Stekyooden. A court proceeding denied this as evidence of the Gistkan people living in the area for over seven thousand years, as their story claimed. They decided to conduct an experiment of their own. Members of the court committee took a core sample of land, and sixty meters down, they found scientific evidence of mud that matches the top of the sacred mountain of Stekyooden, confirming the presence of the Gitksan people. By conducting the core extraction exercise, the committee questioned their knowledge, exited their cave briefly and found a new understanding, one which the Gitksan people already knew. The Gitksan’s story was understood by the committee in the same way the prisoners in the cave understood the shadows. True in part, but by accepting that the story might be true, they were able to find the exit to the cave.

The story, although presented in a spiritual fashion, proved just as accurate as the core sample. So, it is the same when it comes to co-existing. Although it is sometimes a challenge for different groups to co-exist, it is important to remember who’s table we sit at. Some table manners are different in the Ukraine, that does make the wrong? Some evidence is presented as legend, does its presentation make it any less accurate? Who’s company do we share, and what information can they provide us? We must assume that we all are in a different area of the cave and those we speak to have information we do not yet possess. It is only together that we can find our way out into the world of peace and enlightenment.

This brings us to the second concept that I found interesting in the final chapter of the book, the concept of shared ceremony. Chamberlain tells us the story of religious rivalry in Dublin between the Irish Protestant groups and Irish Catholic groups. On page 222 Chamberlain says “both Catholics and Protestants set borders by means of slogans chalked on the walls of buildings” (Chamberlain 222) and that “It was deadly and dangerous to misinterpret the message and you did not want to linger on the borderline. In this case Protestants and Catholics found a shared ceremony by agreeing on “common ground” (Chamberlain 223). This common ground was a mutually understood message written on the walls. Both members of the Catholic parties and Protestant parties understood “the table manners” of this neutral zone and no one would be hurt.

If we mix metaphors to explain co-operation as table manners while residing in a cave then the analogy can be expanded to include borders and title. By creating a title of ownership, we essentially build a wall and block off others from entering our alcove of understanding in Plato’s cave. We reinforce the idea of difference. On this side of the wall (my land) we eat peas with a fork and nothing you can say will change my mind. If we knock down the wall, light from the fire comes in, and new understanding permeates our alcove of current understanding. If we build a table, we eat can together, share knowledge and resources and cooperate to find a route out of the maze of tunnels the cave possess. We must build a shared ceremony so that we can benefit from each other’s company without offence. This set of “table manners” needs to begin at a civic level, and a provincial level and a federal level. The entire structure of our politics needs to change to allow room for our friend’s histories, traditions, and beliefs. We must abandon our concept of my land and your land, and find ways to honour each others existence, knowledge and wisdom.

It is my belief that we must all strive to create a new set of table manners, from scratch, dictated in the traditions of both cultures in equal proportions. Communication is key to success. This communication first comes from the willingness of both parties to cooperate as equals to listen to each others stories and accept both stories as truth. It is not a rejecting of your host’s traditions or one’s own traditions that is the goal, but a mutual respect for the table we both sit at.

To help put with the understanding of the manners metaphor I have included an article, here, that shows differences in manners around the world.

In summary here are some thoughts I’ve taken away:

1. Truth is subjective and “contradicting truths can be equally truthful”

2. In order to co-operate, a mutual language of respect must be developed by sharing a common ritual, based on mutual understanding.

3. No one knows everything. No one system is perfect. Cooperation requires humility and a willingness to adapt, within reason.

Here is a diagram of Plato’s cave.

Found online. I do not own this material.

Works Cited

Oshin, Mayo. “Plato’S Allegory Of The Cave: Life Lessons On How To Think For Yourself.”. Mayo Oshin, 2019, https://mayooshin.com/plato-allegory-of-the-cave/

“12 Lessons In Manners From Around The World”. Wise Bread, 2019, https://www.wisebread.com/12-lessons-in-manners-from-around-the-world.

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?. Knopf Canada, 2004.

Hi Sean,

I really like how you incorporated Plato’s cave into Chamberlin’s discussion of contradictory truths. It helped me really solidify in my mind Chamberlin’s discussion of the topic. My question comes in relation to the court proceeding and finding one’s way out of the cave. The court initially did not believe the Gitksan’s story of the landslide to be proper evidence of the landslide. They had to supplement the story and the traditional knowledge of the Gitksan people with Western science to even only somewhat accept the story of the grizzly bear. As you say, “by accepting that the story might be true, they were able to find the exit to the cave”. What would it had taken for the court to actually leave the cave, instead of just finding the exit? Would they have had to completely abandon everything they knew about Western science in order to fully accept the Gitksan story as the truth?

Hi Cassie.

I’m glad it my approach helped you a little! I understand your question and I think I may have worded that particular piece wrong. What I was attempting to get across is experience is just as valid as scientific evidence.

The Gitksan people have oral history depicting the landslide and that story is tied into the story of the fleeing bears. This experience and history has been entrenched into oral tradition through story. What the story provides that science cannot, is the emotional and trauma of a people who had their settlement wiped off the face of the earth by a landslide. This knowledge provides two things;

1. A historical claim that a landslide occurred in the area

2. Rich emotional history of a people who have, and currently live in the area.

The court proceeding initially rejected the legend as false and had to conduct research in their own way to verify the validity of the claim. Had they accepted the story as oral history as at least partly true; The people working with the Gitksan community could have have began discussions from a place of empathy and understanding rather than a place of skepticism and negative attitude.

My personal opinion is that if the court proceeding had accepted the oral history as valid from the start, diplomatic partnerships may have been easier to strengthen and an understanding of how the Gitksan culture operates could begin to flourish easier.

The court proceeding did not have to reject modern science to validate their own understanding of history. It is my impression that instead of testing the mountain for evidence of a slide for the sake of disproving the claim, they could have entered into an archaeological project WITH the Gitskan people for the purpose of promotion of culture. Either way the result could have been obtained.

The way they approached the project seemed to be confrontational. The way I propose (if done with empathy and understanding) would be forming the basis of a partnership with the goal of education for both parties. Similar projects could be done in the future in the name of archaeological and anthropological history, funded by government committee and led by the Gitskan nation, in partnership.

Getting out of the cave requires being open and seeing opportunity for intellectual, spiritual AND emotional growth and understanding.

It is not enough to approach education with a preconceived bias of truth. Learning does not happen that way. What is true, is what is true, whether we understand it or not.

If the court proceeding found evidence that there was no landslide, then we have new evidence as to what historically happened. More questions are raised and we can begin to find meaning and metaphor in the story. The legend then becomes an anthropological query. Why was the story told about a landslide? What does the story represent? What actually forced the people to re-locate and re-settle years later?

The work could continue in partnership, to determine truth, but now coming from an anthropological or literary analysis rather than a geological one.

In my opinion that is the journey out of the cave.