Although not considered a nation many would emigrate from, Japan, like many countries around the globe has often been the point of origin of citizens spanning many nations, namely in Asia, North America, and South America. The patterns of these emigrational flows are products of history as much as they are of geography, and revolve primarily around geo-political relations, and economic incentives. They are dichotomized, however, by region. As emigration to the Americas, and to Asia is based on fundamentally distinct power dynamics between Japan and those respective regions.

The Americas

The early twentieth century was characterized by several waves of emigration of Japanese laborers, to Hawaii, California, and British-Columbia. These emigrants were known as dekasegi. These destinations changed however, as Japanese sentiment during the period before the Second World War prompted emigrants to shift their prospects from North-America to South-America, namely Brazil and Peru. These migrations ceased with the outbreak of the war, as Canada, the United-States, and Latin American countries closed their borders to Japan. By 1940, about 500,000 Japanese migrants and their descendants were estimated to be living in North and South-America.

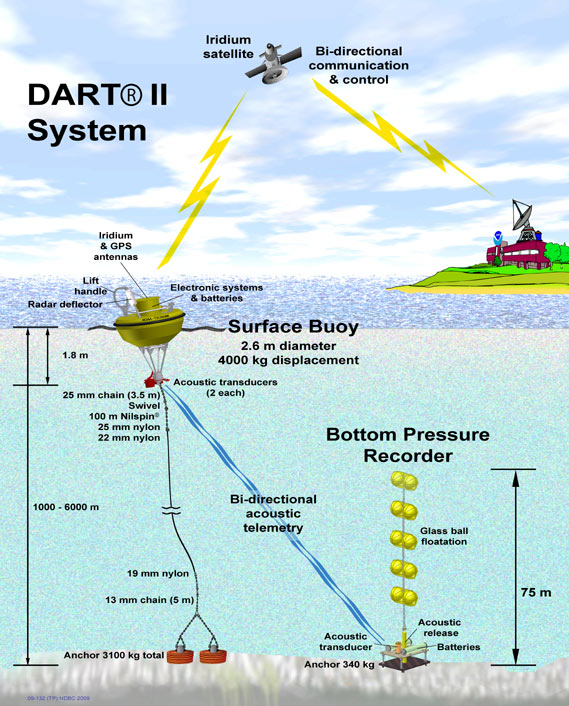

The end of the Second World War reopened formal relations between Canada, the United-States, and Latin American countries with Japan. A small number of Japanese migrants made way for the U.S., Canada, Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina in the immediate aftermath of WWII. These migrations reflected Japan’s post-war devastation, as a lack of employment opportunities, a result of the destruction of key economic centers, coupled with the restrictions enacted under the unconditional surrender, effectively incapacitated the nation and its populace. At its peak, Japanese emigration exceeded 15,000 migrants in 1958. As the Economic Miracle began to take form, these numbers started to dwindle. In 2000, 790,000 Japanese emigrants were permanent residents of the nations they migrated to, of this, around 36% resided in the United-States, and 12% in Brazil. In total, some 1.4 million Japanese emigrants lived abroad in 2000, 670,000 in the U.S., 1.3 million in Brazil, and 80,000 in Peru.

fig. 1. A map detailing the number of Japanese emigrants living in Latin America, divided by post-war emigrants and people with Japanese ancestry as of May, 2000

In an attempt to manage the war-ravaged economy and 6 million civilians and military personnel repatriated from former Japanese colonies and occupied territories in Asia, the Japanese government made attempts to encourage emigration. Central and South American countries were considered to be ideal candidates for emigration, as these nations had a storied history of Japanese settlement. The social infrastructure of previous Japanese settlers existed in these countries, and more importantly during the post-war atmosphere, little anti-Japanese sentiment existed in them. Despite this, many Japanese settlers faced unfavorable conditions and a lack of infrastructure in Latin American countries. Worse yet, the Japanese government did little in addressing these concerns or raising them with foreign diplomats. In 1951, the Brazilian government agreed to accept 5000 Japanese families for emigration into the Amazon region. To aid with emigration efforts, the Japanese government created the Federation of Japan Overseas Associations, setting up a special government corporation to extend soft loans for emigration with funds borrowed from American banks. Under the organization, and ten year emigration plan was devised to send out 426,000 emigrants. This process was anything but smooth, however, as the interministry struggle for leadership between the Foreign Ministry and Agriculture and Forestry Ministry hindered the development of infrastructure needed to improve the land designated to emigrants. The first wave of post-war migrants arrived to the Amazon region in 1953. Less than a month after their arrival, however, many of the emigrant families had deserted their assigned settlements. In total, some 6000 Japanese citizens emigrated to the Amazon region during the postwar era. In 2000, around 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the region, located in three settlements: Guama, Quinari, and Bela Vista.

fig. 2. A Map of the Amazon River detailing some of the settlements Japanese emigrants migrated to in 1953, in this map Belem and Manaus are visible

Asia

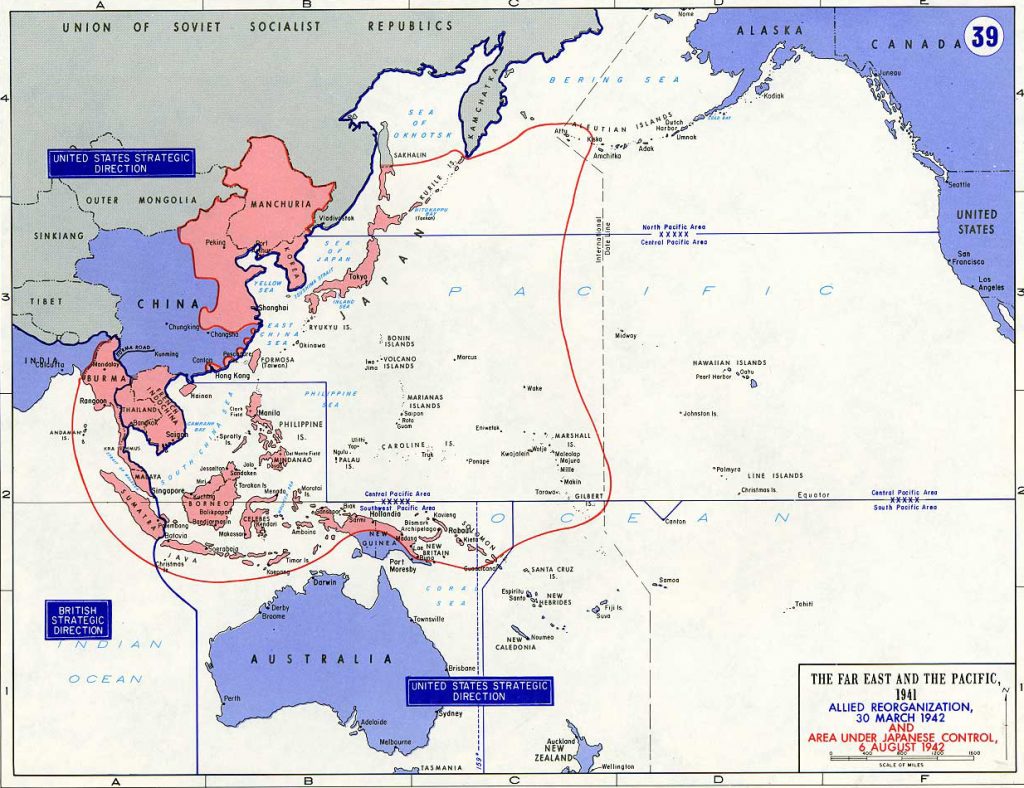

In response to the end of relations with American countries, Japanese laborers emigrated to newfound colonies and territories, such as southern Sakhalin, Taiwan, Korea, and Manchukuo. This was done to alleviate population pressure faced in Japan and to provide relief from the economic depression that had spread since the early 1930’s. In the period between 1929 and 1937, Japanese migrants to Manchukuo increased from 814,000 to around 1.8 million. This was reciprocated with a considerable influx of Korean and Chinese migrants into Japan. Between 1942 and 1945, around 4 million people left Japan (military and civilian) for Manchukuo. To offset this massive drop in population, Japan forcefully migrated some 400,000 Koreans to meet labor shortages. The end of the war ended this emigration/migration flow, however, as roughly 5.7 million Japanese returned to Japan, and 1.2 million Korean and Chinese migrants were returned to their respective countries.

fig. 3. A map detailing the extent of the Japanese Empire, at its height, in 1942

Sources:

Karan, Pradyumna P. “Japan In the 21st Century: Environment, Economy, and Society”. The University Press of Kentucky, 2005. p.187 – 190

Header image: http://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=3264&lang=en

fig. 1. Karan, Pradyumna P. “Japan In the 21st Century: Environment, Economy, and Society”. The University Press of Kentucky, 2005. p. 188

fig. 2. Google Maps

fig. 3. http://www.emersonkent.com/map_archive/pacific_1942.htm