As we near the seven-year anniversary of the 3/11 Disaster, a world of unfortunate memories rears its ugly head. These range from images of tsunami waves engulfing towns, to red-cross campaign advertisements. What characterizes memorable tragedies such as the Tohoku earthquake, subsequent tsunami and nuclear disaster, is a sense that while the pain of such memories lingers, we, as a society, have moved on. We apply a mindset that such events have faded away, and that, while the effects on the lives of human beings may have been significant at the time, a plethora of disasters afterwards has effectively willed the pain of such past events away. However, when it comes to the Fukushima prefecture, and Japan as a whole, like all other disasters, this mindset could not be further from the truth. Six years, eight months, and twenty days later, the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, irrevocably changed that day, are still reeling from the effects of the Nuclear Disaster. The area around the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant has become something of a geographic black hole. With much controversy surrounding the now-dubbed “exclusion zone”, a world of competing narratives makes it difficult to understand the true extent of the damage, both in nominal and theoretical terms. Some former residents wish to abdicate their refugee status and return home. Others are fearful of the long-term radiation damage to the region. Some corporations are pressuring residents to return home, while possibly fearing that the region is still unsafe, while some researchers claim that the extent of radiation damage is overblown. In short, with so many differing opinions, no one is quite sure what the future of the region holds.

Following the magnitude 9.1 earthquake, the subsequent 40-meter tsunami that struck Fukushima triggered a meltdown at the Tepco (Tokyo Electric Power Company) owned Fukushima-Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. 150,000 people, living within roughly twenty kilometers of the power plant, were evacuated. Almost seven years on, and the refugees of the disaster face a new dilemma: judging how much radiation in their former homes is safe. Recovery efforts, thus far, have collected roughly nine million cubic meters of contaminated top soil and washed down buildings and roads. The government’s plan is to reduce outdoor radiation exposure to 0.23 microverts per hour. In September 2014, the Japanese government began a process of lifting evacuation orders for the seven municipalities within twenty kilometers of the nuclear plant. Initial estimates expected up to 70% of refugees to be returned home by spring of this year. As that time has come to pass, it is obvious that recovery efforts, and the lives of the displaced, are far from normal.

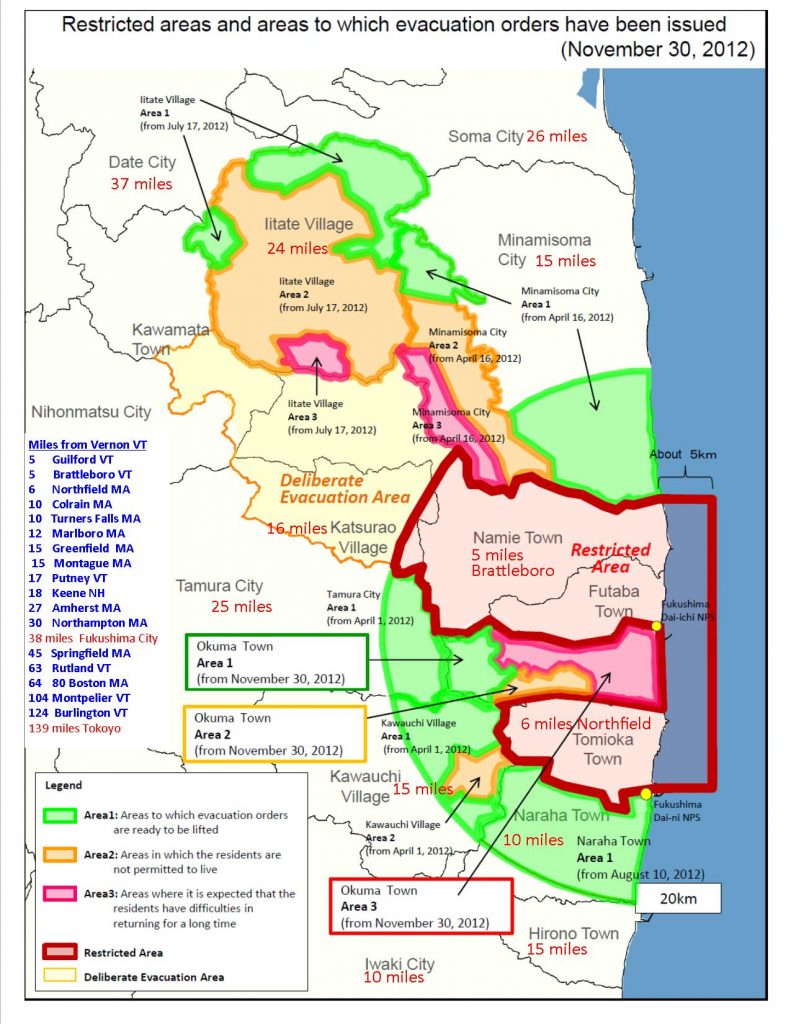

fig. 1. A map detailing the exclusion zone around the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant

Many refugees face a difficult decision between safety and compensation issues. Many claim they are being pressured into returning home, despite radiation exposure levels, they fear, are still too high. Moreover, TEPCO has announced a plan to discontinue financial compensation packages to people who do not return to their former homes, in the evacuation area. In an interview, Katsunobu Sakurai, the mayor of Minamisoma, voiced the concerns of former residents in stating, “There has been no education regarding radiation. It’s difficult for many people to make the decision to return without knowing what these radiation levels mean and what is safe”.

In 2015, Akira Ono, the plant manager, tried to qualm these fears, stating that plant conditions are, “really stable”, and that radioactivity from the nuclear fallout has fallen substantially between the time of the disaster and the time of his interview. Cleanup has been anything but smooth, however. It is still mostly unclear where the nuclear fuel is located in the dilapidated former power plant. In 2014, the manager of the plant, outlined a plan to decommission the site over a thirty to forty year course. It would involve removing melted nuclear fuel masses in tandem with demolishing the site’s four main reactors. In total, this plan will cost roughly $9 billion. TEPCO intends to begin the process of removing nuclear debris in 2021. In December 2014, crews removed the last of the 1535 fuel rods stored in the Unit 4 spent fuel pool. In the beginning of 2015, Ono put the recovery effort at, “around 10%”, complete. With much work still to be done, a major topic of concern is whether residents can return to their homes safely, given they are being pressured to do so, despite obvious indicators as to the safety of the former evacuated zones.

Despite the fears of refugees, and the admitted challenges TEPCO faces with disaster recovery, some researchers rebuke the notion that the entirety of the exclusion zone is uninhabitable. Professor Geraldine Thomas, of Imperial College in London, believes that radiation levels are currently safe, and that the perception created by both the Japanese government, and media outlets around the world has scared refugees into returning home. In a 2016 interview with BBC, Dr. Thomas voiced her views on the situation surrounding the exclusion zone, “People have to feel safe to come back. Many will now not want to come back because they’ve made a life elsewhere. But in terms of radiation, the amount we are getting now is very small, and if you were inside a building you’d be getting even less than standing in the open air.” She views media hysteria as having created a fear around the exclusion zone, essentially promoting an idea that despite data saying otherwise, the area is akin to a Chernobyl-esque forbidden city.

fig. 2. Satellite image showing one of the reactors at the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant as it begins to overheat due to damage from the magnitude 9.2 earthquake & tsunami, on March 11th 2011. (Photo by DigitalGlobe via Getty Images)

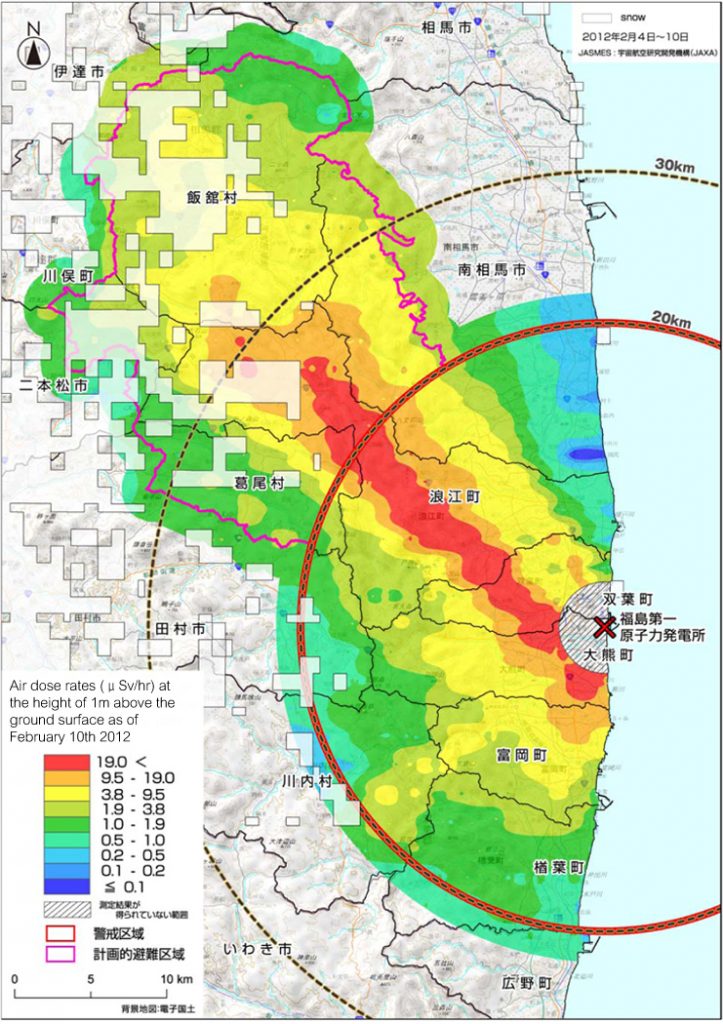

On a journalistic inquiry into the safety of Okuma and Namie, Rupert Wingfield-Hayes, a reporter for BBC, found that radiation levels in the exclusion zone were measured at around 3 microsieverts of radiation per hour. These levels were not measured in parts of Okuma and Namie that have been decontaminated either, they were in non-remediated zones. In theory, if one were to stand in this area for twelve hours a day, for a year, they would only receive an annual extra dose of radiation around 13 millisieverts. Although that measure is not insignificant, it is well below what modern data suggests is harmful to long-term health. Most industrial countries allow nuclear facility workers to receive up to 20 millisieverts a year. Contrast this, and Okuma & Namie’s radiation levels, with Ramsar, Iran. Its background radiation rate measures at 250 millisieverts a year.

fig. 3. A map detailing surface radiation levels in the Fukushima region. (February 10, 2012)

Alas, the issue of relocation is much more complex than it initially seems. The exclusion zone surrounding the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant has become a geographic encircling of controversy. With a plethora of competing narratives as to the safety of the region, the lives of refugees from the region continue to be negatively impacted. Some residents would like to return, feeling a sense of connection to their ancestral homes. Others, still fearful of potential health impacts, find themselves pressured to do so, against their will, by TEPCO. In summation, only time will shed light on how this issue will be tackled. With so many people displaced, all with their own views on the exclusion zone, both TEPCO and government agencies will have to address the viability of returning refugees to the region, sooner rather than later.

Sources

Normile, Dennis. “Five Years After the Meltdown, Is It Safe to Live Near Fukushima?” Science, 2 March 2016.

TEPCO. Fukushima Daiichi NPS Prompt 2017. Tokyo Electric Power Company, 1 November 2017. http://www.tepco.co.jp/en/press/corp-com/release/2017/1464560_10469.html

Wingfield-Hayes, Rupert. “Is Fukushima’s Exclusion Zone Doing More Harm Than Radiation?” BBC News, 10 March 2016.

fig. 1. http://www.safeandgreencampaign.org/action-center/solidarity-with-fukushima-japan/voices-of-fukushima

fig. 2. http://www.vocativ.com/296141/fukushima-five-years/index.html

fig. 3. http://www.japan-reishi.org/news/en_map.html

Featured image: https://imgur.com/gallery/KabxJ